From his earliest efforts, Joe Goode’s work has nodded towards both pop and conceptual movements, yet his sensibilities can’t be nailed down by either. Showing with Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Ed Ruscha in Walter Hopps’ seminal exhibit “New Painting of Common Objects,” it’s fairly straightforward to make connections between Warhol’s stacks of silkscreened Brillo boxes and Goode’s silver-painted six-pack of soda bottles. Alternately, his milk bottle paintings — with both a painted silhouette and actual bottle — can be read as two-thirds of Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs.”

Like a boxer ducking and weaving, Goode’s work moves in and out of artistic camps; with his painted and torn sky/cloud works or shot-up paintings, he both builds up and destroys to produce his finished pieces. Perhaps this model of continuous constructing and tearing down can be seen as a model for the subject of Goode’s latest show, “Golden Dreams.” Through the continual cycles of real estate boom and bust, the architecture around Hollywood and Vine has been both lovingly protected by the preservationist’s hand and unceremoniously slapped down by the wrecking ball. More recently, the new W Hotel and Towers in Hollywood approached Goode and asked him to create something iconic for their new lobby. Having lived some thirty years ago just up the hill from the famous Walk of Stars neighborhood, Goode’s photographs that underpin his paintings are both nostalgic and, because of changes to the neighborhood, unfamiliar and new.

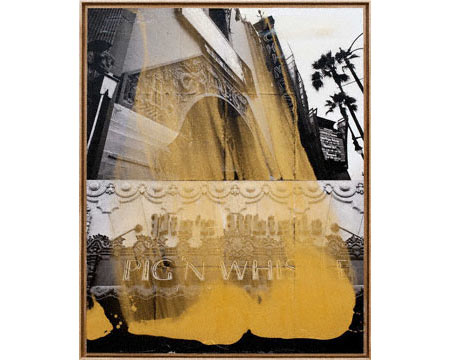

The vertical works rise taller that the viewer; with Hollywood’s over-the-top architecture — from the cylindrical Capitol Records building, to the more recent Hollywood and Highland – the imposing façades teeter drunkenly. For the lower half of the diptychs, the familiar terrazzo stars are underfoot. Mostly bereft of people, the viewing angles are that of the tourist: necks tilted back, ogling the marquees, or shuffling with one’s head down, stumbling over Chill Wills (voice of Francis the Talking Mule) and Veronica Lake. Goode then splashes these images with gold paint, and trowels on a thick impasto of gel medium that is both milky-translucent and clear. Over time, the thick medium will become clearer, an inverse of the smoggy patina that will settle over Hollywood’s more recent structures.

Owing to the nature of the commission, there’s a specificity that is less front-and-center than in Goode’s painted-over depictions, and a departure from his familiar styles. In the early milk bottle canvases, the painted bottle can be seen as being similar to a footnote at the bottom of an academic essay: a reference that supports the argument made above. In a similar way, the "star" on the sidewalk becomes the new asterisk at the bottom of Goode’s art: a reference back to the clichés of mediated popular culture, the same references that enamored Goode’s pop artist peers from his early career.

Published courtesy of ArtScene ©2010