“Art AIDS America,” kicking off a national tour after a brief preview in West Hollywood, CA in 2014, has presently decamped at the Tacoma Art Museum. It is not the first or last contemporary art exhibition about AIDS, but it is the largest in some time and is accompanied by a huge catalogue with numerous art-critical, academic, and political essays by experts on the topic. TAM chief curator Rock Hushka collaborates with Jonathan Ned Katz (University of Buffalo) after the widely admired and controversial “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Self-Portraiture,” which toured the country 2010-2012. This time around, “Art AIDS America” is even more inclusive, the result of a decade’s worth of research and planning. The exhibition can be seen in a number of ways, with or without reading the heavy tome of commentary which sometimes veers towards boring, badly written or hectoring rhetoric.

It’s important to note that another important survey, “From Media to Metaphor: Art About AIDS,” was at Center On Contemporary Art, Seattle, in 1992. That survey displayed 62 artists, with 23 from the Pacific Northwest. “Art AIDS America” has 115 artists, with only six from the Northwest, and 127 artworks. Some of the artists, like General Idea, Robert Mapplethorpe and David Wojnarowicz are in both shows. I miss the other Seattle artists who were so involved in this theme.

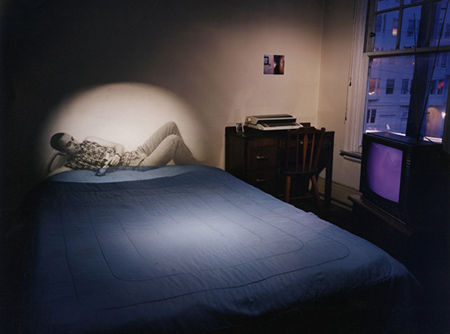

Granted much more room, not to mention grander institutional endorsement, “Art AIDS America” also adds art from the intervening period, 1992-2015. Thus, some of the art on view has a nostalgic tone to it, recalling the activism, anger and tragic sadness of the 1980s and 1990s. Photography is the overwhelmingly dominant medium on view, with big New York names like Mapplethorpe, Nan Goldin, John Dugdale, Barbara Kruger and Annie Leibowitz spotlighted. The biggest installation yet offered any touring show at TAM (all three main galleries), visitors get a thorough drenching in the various phases of art about AIDS in America. Heartbreakingly sad photos of early AIDS victims, like Alon Reininger’s color photo of a dying patient, ended up in LIFE magazine and brought greater attention to the plight many, including President Reagan, were ignoring, or blaming on gays for bringing it on themselves with sexual preferences disapproved of by most Americans. Others, like Goldin’s, show the seamier sides. Some artists, like Albert J. Winn and Mark I. Chester, depict themselves or close friends as they die over a period of years. Others, like Deborah Kass and Catherine Opie, create photographic tableaux both realistic and fantastical. Together, they show how photography was the perfect tool for a variety of approaches to a medical cataclysm that continues, if to a lesser degree, today.

There was the early phase of recognition of AIDS as a crisis; the middle period of activism, legislation, legal battles, and public acceptance; and the current period, after the invention of treatments for AIDS as a chronic illness, that has revived interest in AIDS but, according to the curators and authors, risks nostalgic attitudes or an assimilation of AIDS into the mainstream gallery scene. It is hard to see how many people outside New York or San Francisco might want to live with these images on an everyday basis: they are often horribly grim, not at all shying away from evidence of blood, needles and other related paraphernalia, including condoms.

Strolling through the densely installed galleries, viewers can note AIDS-symbolic artworks that succeeded the angry, early ACT UP-generated ones. For example, abstract art can also carry political or social subject matter, as in the paintings and photographs of Louise Fishman, Ross Bleckner, Izhar Patkin and Andres Serrano. Seen in such a context, the viewer can make up his or her own mind about meaning, a relief after the haranguing works of Kruger, Gran Fury and fierce pussy, the latter two being artist-collectives.

AIDS-symbolic art was a middle-period development wherein imagery is interpreted, as in Bleckner’s snuffed-candle paintings that symbolize AIDS victims passed; or Gober’s leg sticking out from a wall, symbolizing a person in the process of dying or disappearing. These are among the strongest kinds of art in the survey, allowing viewers their own interpretations. Masami Teraoka’s well-known series of mock-Japanese erotic woodcuts with the geisha tearing open a condom wrapper reminds us that AIDS is not restricted to gays. Similarly, the late Seattle artist Michael Ehle’s tall nude of an Indian fakir with many body wounds suggests the agony of early AIDS treatments. Whether AIDS changed contemporary art for good, as the curators hold, will make for good discussions over coffee after the emotionally draining, but moving, experience of “Art AIDS America.”