As a kid growing up in the South I was routinely trotted off to sermons and Sunday school at the Baptist and Nazarene churches favored by my kin. The pastors were always admonishing their flocks to develop “a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” I never quite figured out how to cultivate such a rapport, and by the time I got to college it was clear that the art world was to become my chosen church — and artists, not Jesus, the participants in my most enduring and intimate relationships.

Through the years I’ve had terrible crushes on John Singer Sargent paintings [ See Speer’s recent column, “My Art Crush on Lady Agnew of Lochnaw"—Ed. ] that grew into lifelong love affairs. I’ve fallen for, broken up with, and reconciled with Mondrian, Brancusi, Joan Mitchell, Dan Flavin and Ryan McGinley without ever having met them. I’m not alone in this. Most of us who live and breathe the visual arts have attended at least one exhibition that made us cry and many more that made us passionately angry. Forging a personal relationship with artists and artworks we love, and love to hate, is part of what makes this way of life so rewarding. This is why our current craze for “art selfies” is so unnerving to me.

At well-attended museum or gallery openings these days, it’s damn-near impossible to take a decent photograph of the works exhibited, what with the panoply of rabid selfie-shooters crowding around, vying for the most face-flattering angles. On one hand, it’s hard to find fault with this. After all, isn’t art supposed to provoke reactions, to move viewers to personal involvement and action? What could be more personal than commemorating an aesthetic moment by framing oneself photographically in a direct physical relationship vis-a-vis the art object? And what could be more democratic than digitally disseminating the image and exposing the artist’s work to exponentially more people, many of whom might go on to explore the artist’s output more thoroughly?

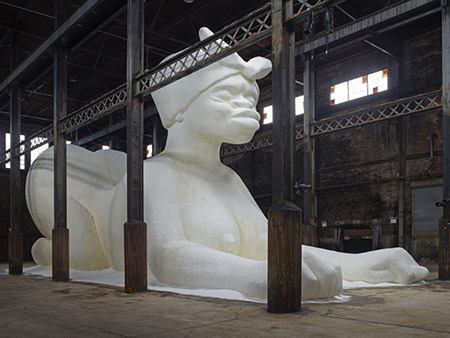

But, people being people, that’s often not the motivation or the outcome. Frequently it’s just about preening, boasting, and hoping to arouse envy: “Look at the glamorous cultural event I dropped in on before a night of clubbing with my posse!” For selfie addicts, artworks are often no more than tools for the creation of visual puns, such as the well-worn illusion of balancing the boulder in Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” at LACMA on one’s index finger. Sometimes the punnery is lewder — witness the cottage industry in vulgar humor that sprang up around Kara Walker’s “A Subtlety,” aka “Sugar Sphinx,” in 2014.

More often than not, artworks function as interchangeable props in an ongoing self-promotional campaign. What the piece is about, who created it, and why, are irrelevant. Last month, when Martha Stewart visited The Broad, she posted pictures of herself to Twitter: a selfie in Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrored Room” and a full-length photo posing beside Robert Therrien’s untitled ceramic-and-fiberglass sculpture. In her captions she didn’t bother to mention the artists’ names or the pieces’ titles (“Such a popular work of art,” was all she could muster), although she devoted two sentences to the long lines.

Certainly, not everyone who traffics in art-selfies is a marketeer, an egomaniac, or a philistine. And fortunately, as of yet there are no thought police digging into our heads to determine whose relationship to art is superficial and whose is profound. But before we push that little white circle at the bottom of our smartphones, we would do well to ask ourselves: Did we come to the exhibit to see the work or for others to see us seeing the work? Do we value the visual arts as part of an ongoing historical and ideological conversation about meaning and context, or merely as an expensive swatch of wallpaper behind our heads? If the latter, then what have we come to as individuals and as a culture? The answers, dear Brutus, lie not in our stars, but in our selfies.