New York artist Chuck Close has deep ties to Seattle and the Puget Sound region. Born in 1940 in Monroe, north of Seattle, he attended Everett High School and Everett Jr. College before the University of Washington. He left Washington for Yale graduate school in 1962. Fifty-four years later, the new Schack Art Center in Everett has borrowed “Chuck Close: Prints, Process and Collaboration” from the Parrish Art Museum on Long Island, NY, where curator Terrie Sultan organized this survey of 89 works. A wonderful introduction for locals unfamiliar with their prodigal son’s enormous accomplishments, it is also a condensed refresher course for contemporary art enthusiasts who often see Close’s work in reproduction because there have been so few exhibitions of his work in Seattle, Tacoma (where he also lived) and Portland.

Sultan concentrates on showing process to the degree that copper etching plates, used woodblocks, printers’ proofs and plastic and metal grids are displayed alongside finished, signed and editioned multiples. As a result, viewers get a wider picture of the 75-year-old artist, who suffered a catastrophic “collapsed anterior spinal artery” when he was 48. The artist’s subsequent artistic accomplishments echo Dale Chihuly’s shift to teamwork after his automobile accident destroyed an eye. Both artists are often paired as Seattle’s most illustrious artists (besides Mark Tobey, of course) who have made it big in New York. Printmaking is just as laborious as glassblowing and both artists have worked closely with master technicians to execute their various projects. In addition, their shared hands-on approach to materials falls loosely speaking under the rubric of craft. The key difference between them is that Close begins with a photograph of a person’s head and takes off from there, while Chihuly hands a sketch to the team and supervises while they blow it.

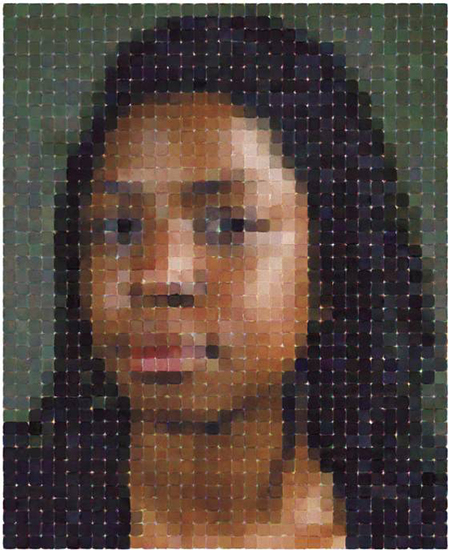

We get to see glimpses of all this studio activity from the first “Keith” (1972) mezzotint, through the dozens of self-portraits in every imaginable medium, and on to the giant-sized carpets and tapestries. If you’ve ever wondered what a lithograph, aquatint, etching, serigraph, woodcut or linocut are, here each medium is presented in depth and explained. All have been used by Close who, since “The Event," paints on an elevator seat with brushes or implements strapped to his wrists. Modular grids receive the paint or ink square by square in a manner that Close lifted from the serial and minimalist art of the 1970s.

What are his themes or, for that matter, what is the meaning of Close’s art beyond the technical bravura or the implausible feats by someone who not only was dyslexic as a child and suffers face blindness (prosopagnosia), but is now wheelchair-bound and, according to biographer Christopher Finch, has been subject to subsequent related post-stroke illnesses? On one level, Close’s content could be the infinity of possibilities with the art of printmaking; on another, the portraits and self-portraits are intense psychological profiles of average and famous people of our age, i.e., they are rife with social meaning. They accumulate into a broad spectrum of friends and relatives, fellow artists, and several notable music, film and fashion-world celebrities. (The latter form Close’s crucial link to Andy Warhol, who pioneered the processed photo portrait.)

Over the past decade, Close turned model Kate Moss into a nine-foot-high Belgian tapestry; heartthrob Brad Pitt peers out of a 19th-century photo invention, the “woodburytype;” and late rock legend Lou Reed became another giant weaving. Art world luminaries like historian Linda Nochlin join other Close SoHo chums such as Roy Lichtenstein, John Chamberlain, Alex Katz, James Turrell and Lucas Samaras, along with younger art-world hotshots Kara Walker, Lorna Simpson and Cecily Brown. Their faces are filtered through elaborately complicated studio procedures that become, for example, the largest Japanese color-woodcut ever made, or a portrait made up completely of dyed-and-pulped, handmade paper wads.

Most interesting to Close fans will be the three-dimensional appurtenances on view; they obtain a sculptural status when isolated in such a well-lit and beautifully designed setting. For example, a plastic waffle grid reveals a view of composer Philip Glass; bent-brass shims are used to depict Close’s daughter; and four woodblocks drenched in colored inks expose Close’s face. Most amusing of all is a custom-cut jig-saw puzzle of Samaras’ shaggy face.

In an age of midcentury abstraction, Chuck Close helped turn the tide back toward representation, but added new approaches to old-fashioned ways of making art. As a result, the most revolutionary figure in contemporary American printmaking helped renew and renovate many aspects of a medium considered passé, but is now unquestionably regarded as fine art.