Continuing through July 2, 2016

For “Surface” Carmen Vetter mixes four large-scale photographs with ten kiln-formed glass multi-panels and diptychs. The Portland artist, trained at University of Nebraska and the ISIS Gallery in Essex, England, also has been artist in residence at Portland’s Bullseye Glass Factory, known for its experimental approaches to glass. In Vetter’s case, she mixes conceptual photography with other approaches that suggest abstraction can carry as much social or political content as any representational artwork. Even though they are overly reminiscent of the gigantic nude self-portraits of John Coplans, a prominent photography critic and editor who turned to photography late in life, Vetter’s body fragment “self-portraits” are equally frank about crepe skin, sagging flesh and the vicissitudes of growing older. Now 58, Vetter’s “Skin” series doubles as terrain, landscape, and looming geological cliffs while they detail body parts such as arm flab, legs and hands.

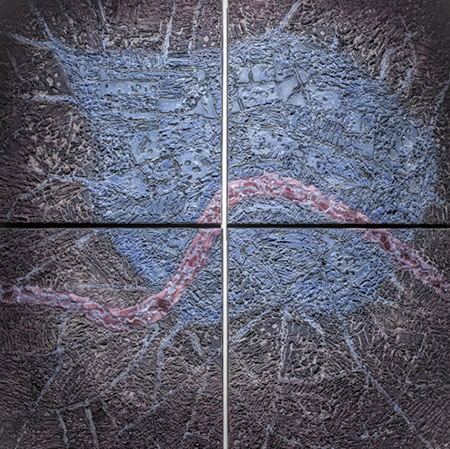

The “Skin” photos are a shaky prelude to the glass pieces, which take off from aerial photos of familiar world capitals. In these, square quadriptychs of glass coalesce into maps of Seattle, Shanghai, Moscow, New Delhi, London and São Paulo. Ground glass powders are scattered and moved about on solid plate-glass surfaces, sprayed, rearranged and fired three to four times each. While the titles suggest beehives of human activity in densely populated areas such as London, Vetter distances the viewer from the direct association with human populations with the use of the grid and burrows deep into surface appearances accentuated by the clumps and fragments of glass. Her insistent use of the grid reinforces the “objective” quality of each work, as if they were elaborate constructs for navigation, aviation or agriculture.

In turn, color plays an important role in delineating areas or sections within each city. The curving pink parabola in “London” is the River Thames; the spiral orange snake in “São Paulo” is a winding automobile thoroughfare at the city’s center. With “Shanghai,” the route of the Yangtze River within the metropolis is traced in crusty yellow-green across the grid, unifying one of the largest cities in the world. One realizes that the diverse sub-sections of streets and neighborhoods perceived are a mixture of Western and Eastern architectural devices, as the city was developed by both European and Chinese architects and builders. The yellow triangles and irregular polygons in “New Delhi” symbolize the roads and blocks, but also the heat of India; the big red blob spreading across “Moscow” seems to be the city bursting at the seams. The nature of 21st-century cities is invoked while simultaneously acting as surprisingly darkened glass panels. Vetter rejects the transparency of glass in favor of the brittle and delicate properties seen here.

Most encouraging of all, “Flux #3,” “Flow #1,” and “Hover #4” sidestep specific geographical suggestions by emphasizing generalized land and water masses. The latter, a small 21-inch square, is dangerously close to a custom tile pattern (high-end backsplash?), but the triptych format of “Flux #3” extends the mounds of crushed glass powders into fantasies of microscopic lichen or musty tide pools. Perhaps a fusion of the “Skin” photos and the map works — and a note for her future — “Flow #1” could also be an MRI brain image, split into two panels with black surrounding areas. Holes, spots and cortical folds inside the white areas suggest that Vetter’s obsession with her skin could work if she switched to X-rays of her body and turned those into glass works, like the impressive ones here that glisten and brood at the same time, not something one normally associates with studio glass.