Continuing through July 9, 2016

Though an artist’s hands are often blackened by the end of the day, the work of making fine art is generally divorced from other types of manual labor. Drawing no distinction between the two, artist Rodrigo Valenzuela, the guest curator of “Subduction," selected works from Harold Mendez, Sharon Koelblinger and Ronny Quevedo to highlight the labor involved in material transformation. It is this labor that serves as the through line for the exhibition.

Mendez’s practice involves distorting, distressing and manipulating found images until they are nearly unrecognizable. “Also in people: parts are wedges: and, to the parts they keep apart (After Sudek)” features a black-and-white image that resembles a crumpled piece of plastic sheeting. See in the gallery, the work seems far away from comprehension, the medium elusive. It could be a photo, or a painting, or a photo of a painting.

In fact, Mendez’s source material was a crisp black-and-white photograph by Josef Sudek (knowing the subject of the original image adds nothing to the appreciation of the work), which Mendez then photographed, printed out, photocopied, and transferred onto a ball grained litho plate that he took a blowtorch to. Each step adds artifacts and veils to the final image. It becomes impossible to know what was retained of and what was imposed onto the original.

Mendez uses a more extreme version of the same process in other pieces, sometimes enlarging a photograph he took of someone else’s photograph or negative, photocopying that enlargement, cutting it into pieces, and manually distressing each piece separately — crumpling, creasing, rubbing bare of ink — before putting the pieces back together, recopying the new composition and making a paper transfer onto Sintra or aluminum. Along the way authorship, subject and meaning become distorted, hazy and reconfigured.

Koelblinger’s photographs are similarly mystifying, her obfuscation of reality even more intentional. A minimalist sculptor by vocation, she grew frustrated with photography’s limitations when it failed to faithfully document her 3-D work. After a period of railing against it, she decided to take on photography as her primary creative practice, exploiting the form’s shortcomings to challenge a viewer’s perceptions of space, dimensionality, color and objects.

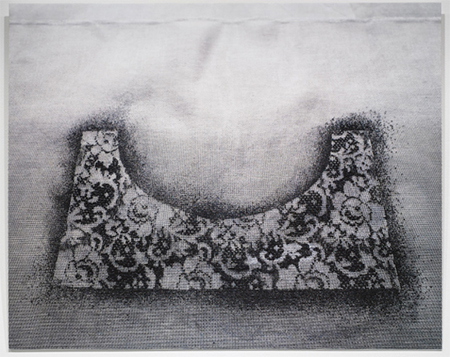

"Star Form 2-50" looks at first like a grainy grayscale image of a floral-patterned collar that's dissolving into a pixelated cloud. Koelblinger arrived at the image by dusting a piece of lace with charcoal powder on top of a metal screen and photographing the pattern that remained once the lace was taken away. Koelblinger works with small grayscale objects, which she photographs in color and presents at a much larger scale. In addition, the piece is mounted on a tilt, with the top hanging farther from the wall than the bottom, in direct opposition to the perspective of the image.

With each of these twists Koelblinger plays gleefully with our exteroception. Despite her straightforward photographing of objects, Koelblinger manages to render them stupefyingly nebulous. In terms of how she arrives at each piece, all are satisfyingly unknowable short of directly inquiring.

Quevedo’s works on paper are by far the most concrete in the exhibition — or so it seems. Images function as colorful geometric explorations of line and form in which straight, curved and dotted arrows covey direction and movement. The artist begins by photographing gymnasium floors and playing fields, transferring their layouts onto paper, while painstakingly retaining their scale. In a process of formalized abstraction, Quevedo overlays maps of movement and migration, an allegory for the journey of the immigrant. Quevedo notably retains all the marks of the process on the final piece: pencil lines, cross hatchings, the thumbtack holes where it hung in his studio. It's a recorded visual history of his labor.

In “Subduction,” a geological term referring to the movement of tectonic plates, the more you look at the work, the less you understand what you’re seeing. The effects of the artists’ labor, of the countless unseen transformations, of the veils and artifacts and obfuscations, come through in mystery and curiosity. Instead of this being a frustration, it feels like the thrill of inquiry for its own sake, without the expectation of reaching a conclusion.