Continuing through September 25, 2016

“Peter Krasnow: Maverick Modernist” is a retrospective exhibition comprised, for the most part, of works from the host Museum’s permanent collection. Looking at its variety, intriguing content and consistent quality, it’s overdue that Krasnow receive this fresh consideration. Curated by Michael Duncan, the project suggests that extensive schooling does not an artist make, but willingness to experiment and to grow, even if it means ripping up geographic roots, enduring material privations and starting several times anew to conquer uncharted creative frontiers.

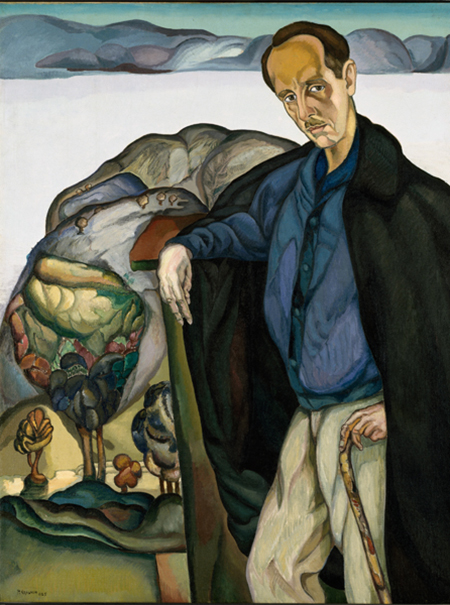

The show begins with a 1928 Gauguinesque self-portrait showing a man with intense eyes, handsome Semitic features and a mien that demands close attention and yet maintains a distance. Equally impressive is Krasnow’s mastery of color that, regardless of subsequent shifts in style, pervades his body of work. This stylistic diversity attests that, innately talented to begin with and having studied art with sufficient depth to learn his craft, he learned most by looking at other artists, be they the Old Masters, contemporary modernists and surrealists, ancient mythological images or folk art as practiced by people he encountered during his travels.

As paintings like “Market Place” (1916), “St. Andrews One Cent Coffee” (1920) and “Under the Brooklyn Bridge” attest, Krasnow lived in the moment when words like symbolism and expressionist were first finding currency, letting his subjects and perceived atmosphere determine his choices of color and style. The same holds true for his portraits which vary from old masterly formal as in “Edward Henry Weston” (1925), to those bearing the imprint of Expressionism as in “Portrait of Olaf Olesen” (1921).

Taking a break from painting, he began to carve wood. It’s the majestic carvings reminiscent of Native American (“Totemic Figure,” 1938) or other tribal totems and sometimes just simple natural forms that carry the show, such as “Praise” (1935) and “Untitled” (1936). As Duncan explains in his cogent catalog essay, those somewhat mysterious carvings brought the public, otherwise prejudiced against modern art, to his door.

Given Krasnow’s heritage, he was not oblivious to the murderous events taking shape in Europe. But he intentionally contradicted the darkness of the times with his use of color. By 1941, his work had morphed into brightly hued geometric forms in works such as “”Untitled” (1941), “K-1 1943” and “K-4 1944 (Architectural Landscape)” (1944-1978).

In the decades following the war, his canvasses remained highly colorful and filled with elements pertaining to Native American symbols and the terrain of Arizona and New Mexico, as in “K-12 1975.” In light of his colorful, symbol-laden ‘60s and ’70’s paintings, wags wondered whether his cultural openness might have led to forays into some form of psychedelia.

Also noteworthy are detailed pencil studies for a stained glass window and temple doors alluding to Old Testament themes, as well as a pencil drawing of a not realized bas relief mural for a Bullocks department store. Contrary to common practice, Krasnow made detailed sketches of his sculptures after he had already carved them.

Fellow Southern Californian Lorser Feitelson, recognized as a creator of Post-Surrealism among other directions in modern art, called Krasnow the youngest old artist in Los Angeles and the oldest young artist because his art does not date but is ever present.

Published Courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2016