In one of my recent articles, I reflected upon meaningful lessons learned from my encounters with three groundbreaking women artists: Lee Krasner, Claire Falkenstein, and Joan Brown. In this two-part essay, I want to pay tribute to a pair of legendary artists who got me thinking about interconnectivity in the sense of what it is to feel grounded to the earth, connected to others, and also to the unknown regions of the universe.

I don't know how often one might mention Gordon Onslow Ford and Al Held in the same sentence. Onslow Ford (1912-2003) was a Surrealist and had an interest in mysticism, while Held (1928-2005) is usually remembered for his contributions to the development of geometric abstraction, and he eschewed spirituality. Yet, in meeting and working with both artists, I discovered that they shared a fascination with the hypothetical structure of the cosmos.

I first met Onslow Ford in 1977, the same year I visited Krasner, while researching the relationship between automatism and the origins of Abstract Expressionism. Onslow Ford had been part of a third wave of Surrealists who gathered around André Breton in Europe during the late 1930s. In 1942, he was one of the refugee artists who relocated to New York City, where he gave lectures at the New School for Social Research during which he demonstrated automatism on the blackboard. By the 1950s, he had co-founded the Dynaton group (with Lee Mullican and Wolfgang Paalen) and built a studio on a woodsy property high up in the mountains of Inverness, California. In a rental car, I drove up the windy roads to interview him and, a few years later, I made a second trip after being invited to stay overnight in his guest house. This time I got to indulge in a European-style feast and walk with the master along an elliptical path that he had carved from his house through the woods and back to the house again — a perfect metaphor for reincarnation (which he believed in).

When talking about the unknown, Onslow Ford was incredibly enthusiastic, as he truly believed in the potential of tapping the unconscious to produce art that might reveal universal truths. His favorite artist was the Surrealist Yves Tanguy, whose automatist painting technique was impeccable and left little trace of the spontaneity involved in creating it. His visionary scenarios were consistently lush and imaginative.

In his own art work, Onslow Ford began depicting the imagined form of the universe in the late 1930s, using a poured paint process known as coulage. To make a painting, he poured Ripolin enamel paints over a canvas and watched the different colors swirl together to form marbleized patterns. Once the paint dried, he superimposed a perspectival pattern over the composition and peeled away layers of paint to create the illusion of deeper planes of space that, for him, signified different levels of consciousness.

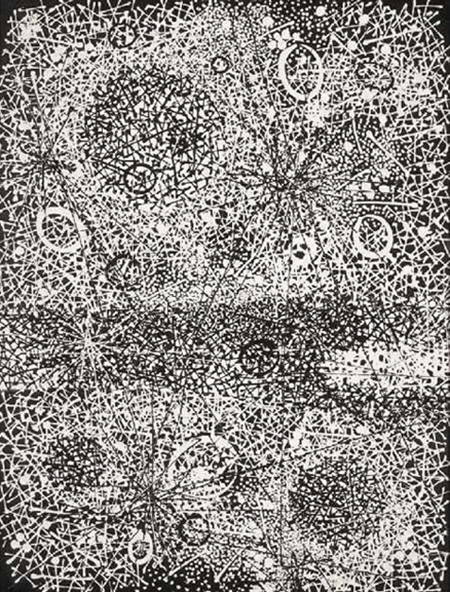

By the 1960s, Onslow Ford had become inspired by Jackson Pollock's drip painting process, and he adopted his own variation of it using a personal calligraphy that he called "line-circle-dot.” As a longtime champion of automatism, Onslow Ford believed that the line, the circle and the dot were the fastest forms one could make, and were thus the most purely automatic. When he flung paint onto canvas, he directed his arm movements to build compositions using only these three elements. In black-and-white paintings such as "Basic Language" (1961, previously titled "Egyptian Eyes No. 2"), which I selected for the 1979 exhibition "Black and White are Colors: Paintings of the 1950s-1970s" at the Galleries of the Claremont Colleges, Onslow Ford articulated his mature vision of what he considered to be the "inner worlds." Using a newly developed aquapolymer paint, he was able to compact layers and layers of his calligraphic notations to form a personal conceptualization of an infinite universe, where matter is synonymous with spirit.

Over the years, I have thought a lot about what Onslow Ford was visualizing, which is the idea that everything is matter, whether viewed spiritually or scientifically. It is within us and without us. So with this in mind, it is easy to understand the basic principal that everything is interconnected by that invisible matter, or spirit, that bonds humans, planets and the unknown regions together as one.

In my final conversations with Onslow Ford, which occurred in the mid-1980s while I was Director of Exhibitions at the San Francisco Art Institute, he was himself observing parallels between spirituality and science. His favorite book at the time, in fact, was Fritjof Capra's "The Tao of Physics," a comparative study of Eastern Mysticism and physics.