Continuing through January 8 (Menil) and October 29 (McClain)

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) is still considered one of the most innovative, prolific and influential artists of the 20th century. The number of artworks he produced has been estimated to be around 50,000, and none provide as much insight into how he conceived and developed his ideas than his drawings. Most would agree that he was one of the most accomplished draftsmen in modern art. “Picasso The Line," organized by the Menil Collection, presents an amazing 90 original works on paper executed in pen, pencil, charcoal and collage. The show includes drawings from public and private collections in the U.S. and Europe, several of which have never been seen in this country. There are also rarely exhibited works from the Menil’s collection of Picassos.

One notable piece is “Self-Portrait (Autoportrait)” (1918). Borrowed from the Musée National Picasso in Paris, this charcoal and graphite drawing on paper reveals the artist’s masterful control of line. It is a three-quarter portrait of the young Picasso turning his head slightly to gaze over his left shoulder at the viewer. With a few decisive strokes the artist depicts his expressive oval eyes, large nose and perfectly shaped lips inside a thin, continuous line outlining of his forehead, cheeks and chin. A few more strokes and the hairline and ear come into focus, while subtle shading with charcoal suggest his hair and shoulders. Picasso drew continuously throughout his life, and "The Line" includes drawings from the many distinct periods of the artist’s long career, including the African-inspired phase, Cubism, Classicism, Surrealism and post-World War II.

“Bottle and Glass on a Table” (1912) is a cubist drawing with just a bit of newsprint applied strategically to the surface. Using an economy of lines, Picasso evokes his earlier cubist café paintings, with the suggestion of a table upon which rests a bottle and glass, complete with garnish. All it takes is a small scrap of yellowed paper with part of the masthead from LE JOURNAL and a fragment of headlines to evoke café life in Paris. While Picasso’s drawings have been the focus of many exhibitions, this one, guest-curated by Museo Picasso Málaga Founding Director Carmen Giménez, considers the position that these works hold within the artist’s oeuvre. A fully-illustrated catalogue examines the role of line in pieces owned by the Menil Collection as well, which is the organizer and sole venue for the show.

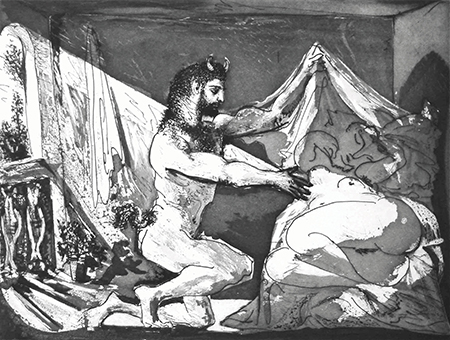

A companion show of prints, "Imagining Backwards: Seven Decades of Picasso Master Prints," explores Picasso's printmaking techniques and includes numerous portraits of his most famous female muses — Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Francoise Gilot, Genevieve Laporte and his second and final wife, Jacqueline Roque. Presented at McClain Gallery are more than 50 prints dating from 1905 to 1970. Like the Menil show, this mini-retrospective includes work from Picasso’s many periods. Photographer Dora Maar was 28 when she met Picasso, and she quickly became the principal woman in his life and art, despite the fact that Marie-Thérèse had just given birth to the artist’s daughter and he was still married to, if long separated from Olga Khokhlova. In “Head of Woman No. 7 Portrait of Dora Maar,” a colored engraving from 1939, Picasso revisits elements of his earlier cubist portraits, presenting multiple views of Maar, her hair in a ponytail and tied with a large blue bow. Highly stylized, the piece still conveys the young woman’s youth and beauty.

When Picasso met his last wife, Jacqueline, he was 46 years her senior, but he pursued the 26-year-old relentlessly until she agreed to marry him in 1961. During their 11-year marriage, and before Picasso died in 1972, he did some 400 portraits of her, more than any other woman in his life. “Portrait of Jacqueline’s Face” is a 1962 linocut that references late cubist portraits of Dora Maar such as the one discussed above. This piece is less scrambled than the earlier one, but it still presents Picasso’s signature multiple perspectives and is dominated by Jacqueline’s large dark eyes and strong profile, which reminded him of the 19th-century French female portraits he so admired. The show is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog with essays by art historian Charles Stuckey and a forward by Picasso expert Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

To have such a wealth of Picassos assembled in one city at the same time offers an opportunity to revisit the creative genius who dominated the last century. From his first gallery show in Paris in 1901 to his final series of prints produced in the early 1970s, Picasso forever altered the course of Western art and our perception of the world around us.