Continuing through November 26, 2016

With an expected uptick in the rise of contemporary social and political art, and the added impetus of the recent election, it is salutary to re-evaluate anew the history of politics in prints. Co-curators Shayla M. Alarie and Miranda K. Metcalf draw from their vast inventory to explore at a quick clip five centuries of European and North American attitudes toward protest, dissidence, satire and propaganda in “Pick Your Poison.” The show proves that all of these impulses can rise to the level of art when elegance of execution and mastery of subject transcend any dated of-the-moment image or message.

To have Dürer as well as Goya, Käthe Kollwitz, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg all in one show should be tempting enough to make this a must-see appointment. Who would have thought Dürer, the inventor of etching, could be funny? As one scholar put it, Dürer “ranks higher as an engraver on metal or designer of woodcuts than as a painter.” A woodcut, “The Ranks of Man” (1498) illustrates a moralistic theme, the “Ship of Fools,” which was an early hit with literate Germans. The artist places humans and donkeys on a rotating torture wheel, all the easier to confuse the two. Precarious balance is also the subject of “Political Seesaw” (c. 1830) by Charles Grandville, with children, dressed in politically symbolic red and green suits, taunting friends and enemies who are looking on.

When Goya died in political exile in Bordeaux, France in 1828, he left behind “The Disasters of War” (1810), his dark meditation on the Napoleonic Wars in Spain and their aftermath. In “May the Cord Break,” a Catholic priest is on a tightrope, terrified by the gleeful crowd, angry that the Bourbon kings are back on the throne thanks to the help of the Church. Set during the wars to repel the French, “And This Too” depicts famine among dying family members, civilian casualties produced by years of senseless territorial gains and losses. By the time of “Will She Rise Again?” a deep blue female corpse grasping amid the rubble, Goya is pondering whether reason and freedom can ever return.

We are reminded that the past century began with art serving propaganda willingly, as in T. A. Steinlen’s gorgeous color lithograph, “Save Serbia Our Ally” (1916) and H. P. Raleigh’s “My Daddy Bought Me a Government Bond of the Third Liberty Loan, Did Yours?” State military coercion of a civilian population would never be clearer — or more tragically misguided — than in World War I. Kollwitz is represented by three brilliant, surprisingly stylistically varied, examples of her printmaking genius. In “Unemployment” (1908), four starving children and a dying mother lie in bed by a brooding, seated father. The “March of the Weavers” (1897) group comes complete with peasants’ weapons in the form of hammers and sickles. Based on an actual event, the Silesian weavers’ rebellion of 1844, that was the source of a famous play, “The Weavers” (1892) by Gerhart Hauptmann, Kollwitz was also tapping into an impeccable German pedigree of protest art and literature. Stephen Csoka's “Fatherless” (1946), with its crying widow, is a virtual tribute to Kollwitz made shortly after her death. Farther back historically, “Amistad” (1989) by Jacob Lawrence, depicts the unsuccessful slave boat rebellion of 1824. It is a great example of Lawrence’s fusion of social realism and cubism.

The Korean War plays an unusual role in the exhibition. Two prints suggest extremely different ways of expressing anxiety and even gratitude toward the separation of North and South. Paul Jacoulet, whose parents moved to Japan when he was three, dedicated “The Two Adversaries” (1950, the left, “Korea,” is exhibited here) to President Truman for his intervention in the conflict. A shirtless man holding a white rooster is crouching in peasant trousers before a mountain renders its power neutral. Less symbolic but still subtle, “Look at the Birds in the Sky” (2003) by South Korean artist Lee Chul Soo, places missiles, jet fighters and other airborne weapons associated with the North in a striking woodcut.

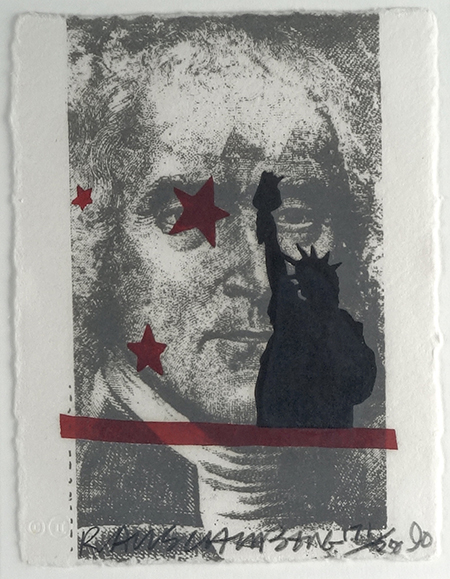

Johns and Rauschenberg each made a print series that was sold to help raise money for an African-American political candidate, Harvey Gantt, running for the Senate in North Carolina in 1990. Johns’ signature “duck/rabbit” visual conundrum is typically ambiguous, while Rauschenberg’s high-contrast image of an aging Thomas Jefferson is overlaid with a dark silhouette of the Statue of Liberty.

Finally, perhaps the most urgent victim of political and social conflict today, the powerless child, is captured in Marcelle Hanselaar’s hand-colored etchings “Child Soldier 2” and “Child Soldier 4” (2014). Clearly African, but ambiguously male or female, Hanselaar’s treatment restores dignity and beauty to ravaged and persecuted children. Ubiquitous, burning oil fields are seen in the distance, observed by the youth with his or her back to the viewer.