Ever since I studied aspects of Jungian psychology and absorbed the music and lyrics of The Police, I have held a fascination for synchronicities and correspondences. From observing these things I've learned that, even when sad events and tragedies occur, timing can be both poetic and logical. Right now, many of us who knew Arnold Mesches are feeling the loss and accompanying sadness of his recent passing. But I think Mesches himself accepted and probably welcomed what was happening ... I know that Allen Ginsberg did when he knew it was his time to transition.

A few weeks ago, after I e-blasted a newly published essay to friends and colleagues, I received an email back from Arnold informing me that he was dying from leukemia. While it is not shocking for a man in his early 90s to be approaching death, I was certainly startled by his frankness, which is something that I truly appreciate.

I first met Mesches around 1981. I had been mesmerized by his large scale portraits, and wrote a favorable review of them for Art in America. What I particularly admired about these portrayals was the fact that each face is shown immersed in a matrix of abstract expressionist brush strokes. The artist had mastered bravura brushwork, and for this reason he is often thought of as a painter's painter. If we look at his content, however, it is significant to point out that he also solved the problem of how to depict the same concept of interconnectivity that I discussed in my recent article on Gordon Onslow-Ford. It's all energy, and we are part of it.

Having resolved for himself questions about the human connection to the universe, Mesches next moved on to what he cared about most, social justice. Influenced by the Cal Arts approach to disseminating information geared towards visual thinking, he started juxtaposing emblematic images, but continued to employ the bold abstract expressionist brushwork that his generation invented. For the remainder of his career, this painting technique served him well as a vehicle to heighten the expressive impact of his visual lexicon of images that, when conjoined, express a humanistic vision of peace and equality.

Mesches' imagery wasn't the only thing that changed in the early 80s. He also decided to leave Los Angeles, where he taught for many years at the then-called Otis Art Institute, and moved to New York City. The timing was fortuitous. It was the height of the Neo-Expressionism phenomenon, and he was readily embraced. Mesches' work was quickly exhibited at a small East Village gallery run by Jack Shainman, who today operates two globally successful gallery spaces in Chelsea, and a third in Kinderhook, New York.

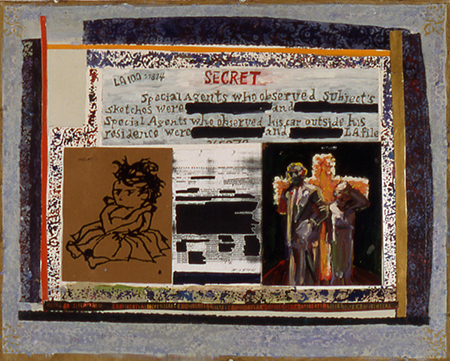

Of all of Mesches' projects, the one that probably achieved the widest reach and largest impact was his series "The FBI Files," which traveled extensively. I had the privilege of bringing it to the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans in 2004. The exhibition consisted of collages that Mesches made using the documents that the FBI had kept on him from the McCarthy Era through the 1960s. In the 50s, the young artist worked on Hollywood sets, while maintaining his own studio practice. With Hollywood under attack by McCarthyites, he became a conspicuous target in the eyes of the FBI.

In the late 90s, Mesches decided to obtain the nearly 800 pages that the FBI had kept on him, which was his right under the Freedom of Information Act that was passed in 1967. Names were blacked out with markers, but he was of course able to figure them out. As he reviewed his FBI history, he learned that a woman he once slept with had been spying on him. He also solved a mystery about why a student wore a tie to a studio art class in the heat of summer and refused to take off his jacket. It was because he had a camera hidden in his tie. When I interviewed Mesches before an audience at the CAC, he talked about the time during the Red Scare that his studio was ransacked, which he attributed to the FBI.

In the collages, Mesches combined pages from the files with photographs, news clippings and his characteristic abstract expressionist brushwork to tell the story of McCarthyism. With his passing occurring during the same week that the FBI once again overstepped the boundaries of its authority to contribute to the election of a demagogue, another weird synchronicity has occurred, and the art of Arnold Mesches seems to me as relevant as ever. It would be wise for institutions to start showing "The FBI Files" again, especially in rural America, so that we can restart the education process and march to the credo, "We must never forget.”