Continuing through June 18, 2017

As we come to the centenary of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s "New Vision" and continue the twenty-first century largely without a vision of our own, it seems pertinent to examine the peripatetic career of one of the most eloquent inventors of new art for a modern age.

Absorbing the artistic ideas of the post-war decade, the Hungarian artist was buffeted by the hot wind of Dada and the swift currents of the Russian Revolution. He gravitated to Constructivism, absorbed the penchant for the machine emerging in Berlin, and signed on with the De Stijl artists. A prolific author, Moholy-Nagy wrote about everything he learned, circulating the explosion of experimental ideas that were replacing old clichés. It was more for his writing than his still-developing art that Walter Gropius hired him to teach at the Bauhaus in 1923. Here in Dessau the Hungarian wanderer found a home, an institute that encouraged his polymath mind and allowed him to dart from painting to photography to sculpture to graphic design. His many enterprises were linked by his fascination with the play of light and shadow in three dimensions and with the intellectual play with perspectives in two dimensions.

Along with Man Ray and Christian Schad, Moholy-Nagy rediscovered photograms, the exposure of objects on light sensitive paper, an old form of camera-less “light-writing.” By returning to the very beginnings of photography, he explored the layering of dark and light while exploiting the reversal between negative and positive. The abstraction of the early photograms was related to the severe and restrained geometric paintings, where the absence of the artist’s “hand” is significant. Wielding rulers and sharp pointed pencils like swords, the artist incised his lines and scored with a compass, leaving grooves to half the flow of smoothly applied paint. He functioned, as his second wife explained it, “like a gem-cutter.” Refuting the fiction of Renaissance perspective and its imposition of control upon an unruly world, the ambivalent shapes, conceived with ruler and scoring pencil, shift and slide, as if seeking the once-firm ground, passing in front of one another in a subtle transparency.

Moholy-Nagy was so determined to avoid texture and ensure the absence of painterly qualities, he famously conveyed instructions through a telephone conversation with a sign factory that produced a series of paintings from them. The exhibition brings this series together, and, although the gesture by the artist has become associated with proto-Minimalism, he never repeated the experiment. Inspired by mechanical drawing, these machine paintings were part of another hands-free enterprise, photomontage. Dada artists were undoubtedly the source, but their works are crude and clumsy compared to Moholy-Nagy’s aerated montages and carefully poised found photographs. The exertions of the straight line, cutting pencil and exquisitely deployed razor situated attenuated images against blankness, agitating space into indecisive perspectives with ruled pencil lines.

As if he were not content with the limitations of the obdurate picture plane, Moholy-Nagy experimented with the new plastics. His Plexiglas works, fragile and precious, allowed him to combine the ambiguousness of transparency and the presence of shape with the transformation of painted stripes of paint into shadows and the mutation of texture into shaded shapes slanting from the point of origin. Controlled and yet ambiguous, perhaps predicting an uncertain future, Moholy-Nagy’s creations shared a light touch with a breathing space full of possibilities.

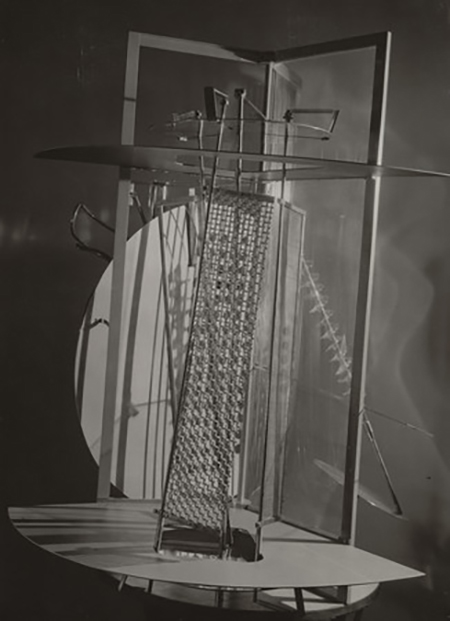

In contrast to these fragile experiments, his inventive and kinetic “Light Prop for an Electric Stage (Light-Space Modulator)" is surprisingly sturdy and large. Designed for the artist to use to demonstrate plays of light and movement, this beautiful construction is a photogram in three dimensions, as if negative shapes have leaped into being as positives, asserting their materialized presence. A promoter of contemporary photography, the artist rested his “New Vision” photography upon an insistence upon re-seeing the world from new perspectives that renounce old points of view. Moholy-Nagy asserted that the Eiffel Tower should be re-viewed as a sculpture, so he photographed it from the ground, craning upward.

When he left the Bauhaus in 1928, he photographed the Berlin Radio Tower in a series of images from the top down. It would be a mistake to read the oeuvre of this artist as a formalist experimenter, for the artist was a dedicated communist whose “new vision” was a political one. His leftist leanings meant that he was marked as an enemy of the state in Nazi Germany. Moving quickly from Holland to England and finally to America, László Moholy-Nagy finally found a permanent home where he could reestablish the Bauhaus in Chicago, where he would meet his untimely death from leukemia in 1946.