Continuing through July 23, 2017

The austerity of color, form and composition that defines Minimalism in here means contentedly losing ourselves in an all-orange cross-shaped canvas by Robert Mangold, meditating upon the slim lines and broad shapes in a Theodoros Stamos painting, or pondering why Beverly Pepper lets a small, geometric stainless steel sculpture bend around its square white base.

“Poetic Minimalism” is an attractive, soothingly lit arrangement of more than two dozen works drawn from the museum’s collection of big-name abstract artists that also directs attention to regional artists exploring the minimalist aesthetic. As the curator’s introduction to the exhibition explains, the paintings and sculptures selected generally adhere to the style of spare lines, monochromatic hues and reductive forms. But at the same time, many of them give off hints of personal expression or suggest humanistic messages. That’s where the “poetic” aspect comes in.

An example is “Manascritto” (1980) by Italian painter Alessandro Algardi. Our first impression of the all-white canvas is to confirm its adherence to minimalism. But a closer viewing reveals straight lines of densely layered, indecipherable script filling the canvas one row after another. The work celebrates the fluid, gestural and repetitive quality of handwriting.

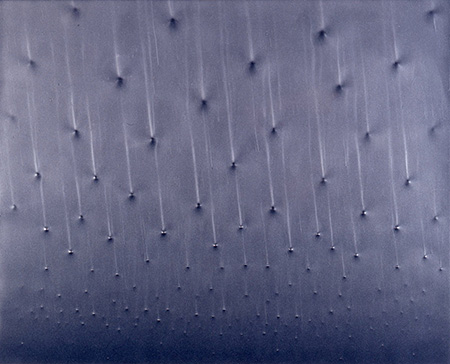

Another example is the visual playfulness of New York artist Jason Young’s “Silver Tap” (2004), in which he mixes acrylic paint with resin on alloy to create what appear to be numerous pods or bumps moving across what is in fact a flat, silver-blue surface. Viewers can’t help but think that the bumps are protruding from the surface, but it’s a trompe l’oeil effect that turns the coolness of metal into a warmer, organic surface and invites thoughts about nature.

Although the exhibit includes several internationally known artists, it also has a fair share of Arizona artists or artists with regional connections. Olivier Mosset, a Swiss artist who lives part of the year in Tucson, is represented by the monochrome-shaped painting “Untitled (Swiss Coffee) #2” (2001), which asks viewers to accept art at its most basic. A particularly meditative piece by Ben Goo, “Untitled” (1971), is composed of a simple circle balanced above double rectangles in soothing tones of pale blue, pink and white. Goo, who also works in wood and marble, taught at Arizona State University for four decades. The chine-collé piece by Johnnie Winona Ross from Taos, New Mexico, titled “Salt Creek Seeps XII” (2003), is composed of pale stripes with a suggestion of dripped paint to telegraph erosion or the passage of time.

One of the most surprising pieces is “Stills” (2014) by Marie Lund, a London-based artist whose work is a found curtain on wood stretchers. The curtain comes from Paolo Soleri’s utopian architectural project Arcosanti in central Arizona. The gradations of color — bleached-out pinks and reds — perfectly evoke the harshness of the desert, along with fading memories.

Unlike early Minimalism of the 1960s, in which the art object is reductively idealized, these artists prove that their work can communicate an array of poetic, dramatic and expressive ideas. In a tumultuous world it’s a needed dose of Zen.