Al Held shared Gordon Onslow Ford's interest in cosmic structures, which I discussed in my recent column on the third wave Surrealist. Unlike Onslow Ford, however, Held did not develop this interest until the later stages of his career.

I first learned about Held's art while I was organizing the same 1979 exhibition, "Black and White Are Colors," in which I exhibited a classic Onslow Ford painting. As it happened, I included both artists in the show. Although their focus and intentions were worlds apart, Held created one of his most celebrated bodies of work in the 1970s when he, too, turned to black-and-white. For Held, who began as a second generation abstract expressionist and then moved on to geometric abstraction, a black-and-white palette made it possible for him to clarify issues of flatness and illusion, which were among the hottest topics in art criticism at the time.

I didn't get serious about Held's art, however, until two decades later. On a visit to the Museum of Modern Art in the late 1990s, I had an epiphany while standing in front of one of Held's larger alphabet paintings. I was mesmerized by its power and concluded that Held was greatly under-rated. So, with the help of another artist who was a friend of his, I approached Held about my desire to propose him for the 1997 Venice Biennale. When he wasn't chosen, I proposed him once more in 1999. Again he wasn't selected (and he was bummed).

My extended dialogue with Held didn't really take off until the turn of the Millennium, when he invited me to write the catalog essay for his exhibition at Robert Miller Gallery in 2000. Our discussions continued through 2002, when I organized an exhibition of his later paintings for the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, where I also engaged with him in a public conversation.

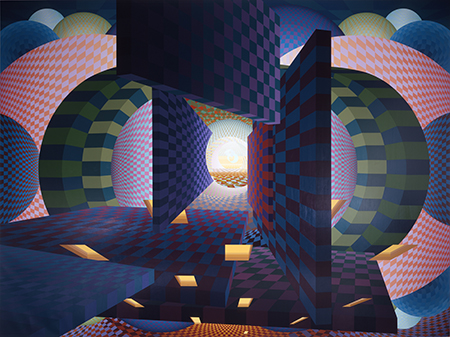

In preparation for writing the essay for the Robert Miller exhibition, I met with Held at his studio in Boiceville, New York. By that time, he was making mural scale multicolored paintings of imaginary, labyrinthine universes. The visual ideas for these works originated in small watercolors that he made each year in his other studio in the Italian countryside. In the Boiceville studio, Held would make two or three acrylic paintings based on visual ideas introduced in the watercolors, with each becoming larger and the imagery revised over periods of several months. Too old to get up on the scaffolding himself, he worked with a dedicated staff of assistants, who would do much of the taping and sanding of each painting's surface so that no trace of the artist's hand would remain visible. Held turned his back completely on the abstract expressionist gestures of his 1950s paintings because he now wanted all focus to be on the content, and not on the artist's ego seen through traces of his hand movements.

For Held, the all-important content that so exhilarated him was tied to his new mantra that "everything is interconnected and constantly expanding." Held had recently learned about string theory, and thus used his intuitive faculties to visualize structures based on ideas that were being espoused by scientists, as opposed to art critics.

In our conversations, Held was very precise when it came to discussing the space in his new paintings, which he referred to as "non-gravitational and multidirectional." In these late works, there is a real sense of exuberance and playfulness. Bolder with color, light, and patterning than he ever had been before, Held was now painting kaleidoscopic visions with multiple points of entrance for viewers' eyes. With their wonderful complexity, these are paintings that call out to us to wander inside them, to discover one universe leading to another and to another. Whereas Onslow Ford's paintings teach us that the cosmos is one unified whole, Held’s canvases open doors to its many parts; both artists grant us permission to think about unknown spaces as fields for exploration, adventure, and discovery.