The death of emeritus professor of art Francis Celentano (1928-2016) brings to an end a long pedigree of the University of Washington School of Art, its close links to European artists and art schools birthing modern art in the past century. Celentano’s 1958 Fulbright year in Rome changed his life after his encounters with hard-edge painter Piero Dorazio and other members of the burgeoning optical perceptual painting movement. Not only one of the first scholars of Abstract Expressionism, Celentano studied painting privately with Philip Guston for a decade and was acquainted with all the members of the New York School at the Cedar Bar. These encounters led to the first graduate thesis on Abstract Expressionism, Celentano’s “Origins and Development of Abstract Expressionism in the United States” (M.A., 1957) written under H. W. Janson and cited by Harold Rosenberg in his monograph, “De Kooning” (1973), among many others.

We will never know what else happened in Rome that year, but when the 30-year-old art historian and nascent abstract expressionist returned to Manhattan, his rejection of the New York School was complete and utter. He remained hilariously contemptuous of the movement for the rest of his life in conversation and in print. For example, his 1991 unpublished eulogy for Robert Motherwell was really an attack on the older artist (who was born in Aberdeen, Wash.) and his cohorts. Celentano’s re-definition of Abstract Expressionism was priceless: It was “a disturbing environmental and painterly oil pollution that spread throughout the leading industrial countries.” He accused Motherwell of “soft mental ooze,” guilty of a type of painting “which puddles lines and drips oil blithely enhancing the adult myth of a child-like ideal for expulsive permissiveness.” In other words, such painting was akin to a baby defecating.

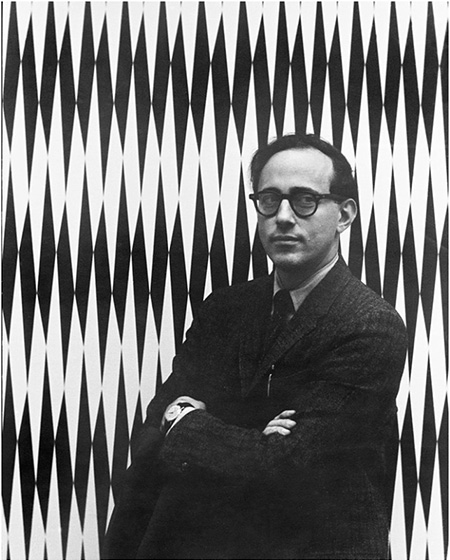

Hired by UW School of Art director Spencer Moseley (who had done postgraduate work in Paris with Léger), Celentano warmed to Moseley’s bent for color theory, chiefly that of M. E. Chevreul, a 19th-century theorist who held that the juxtaposition of two complementary tones heightened their intensity and that chromatic properties change when set next to black. Upon arriving in Seattle in 1966, the Bronx-born Italian-American unleashed a fast-moving train of work that remained on track for 50 years, until his death last year at 88. The huge black-and-white “Reversible Units” (1966), perhaps his greatest work, answered Bridget Riley’s feminine curves with rigid, monumental, interlocking, stiletto-dagger stripes that were more masculine and assertive than Riley’s lacework.

Thanks to the example of two graduate students experimenting with automotive spray paint, Celentano followed suit and never picked up another brush. The results were methodically colorful, like Chevreul or Josef Albers. The cerebral and systemic permanently replaced the subjective and open-ended, unfinished look. The total opposite of the New Yorkers in that sense, each picture’s outcome was determined ahead of time, working backwards so to speak, with tall thin sprayed strips of PVC plastic, cut up and glued back together, then switched end to end.

These were not the paintings to which New York had paid attention when he was younger. Those works, such as “Lavender Creed” and “January 20, 1964” (both 1964) were pre-Op, more hard-edge, with the latter appearing in “The Responsive Eye,” the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibition that birthed the Op Art movement. It wasn’t until decades later that his involvement with Howard Wise Gallery and his inclusion in the pivotal “International Artists Seminar” at Fairleigh Dickinson University in 1965 were acknowledged. Columbus Museum of Art curator Joe Houston borrowed “Phalanx” (1965) and “Kinetic Painting III” (1967) for his “Optic Nerve: Perceptual Art of the 1960s” in 2007.

Over the years, working uninterruptedly, Celentano explored canvas shape, added electric motors, branched out to sculpture with colored, tall cylinders, and completed a 42-foot wide mural for Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in 1972, “Spectrum Delta II.”

In another dialectical turnabout, some of the paintings satirized the gigantism of AbEx, shrinking to 24 inches wide yet 12 feet high. Building on mathematical structures aligned to alternating repetitive systems, Celentano’s demonic productivity accumulated to extravagant proportions, eventually displayed at two retrospectives, one at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington in 1994, the other at Hallie Ford Museum of Art in Salem, Ore., in 2010.

Despite occasional critics who thought the work exhausted or trivial (“optical trickery,” as Ron Glowen put it in Artweek), Celentano was revered by other critics and students. According to Prix de Rome fellow and colleague Michael Spafford, “Students told me he gave them the most brilliant descriptions of color of any teacher they had … Once, when we went to New York, he let us use his loft and we saw tons of his Abstract Expressionist paintings in the racks.”

Eventually, the New York gestural works were removed to Seattle and carefully stored — but never exhibited. Celentano would appear wounded or offended when critics or curators inquired after them. Sadly, chief interest today in New York is for these works, possibly because of their connection and similarity to his mentor Guston.

However, Pacific Northwest art museums, galleries, collectors and critics loved the later Op art works. After all, Celentano was like a rare, formerly extinct species: an Op artist who didn’t realize the movement was dead, buried, vilified and ridiculed for its decorative superficiality. The transplanted New Yorker survived all the dismissals, attacks and neglect. Adapting easily to computers, he intensified the complexity of his compositions even more, as in the “Electra” (1990-92) series. Returning to the big wide AbEx rectangular format, the artist in his 80s filled expanses of canvas with rows of tiny repeated shapes against a cool blue background.

Favoring the land of fellow color-scientist Chevreul more than the precincts of New York or Seattle, Celentano’s final years involved extended stays in Paris, affirming his international roots and temporarily exiling himself from the American cities where he had flourished, foundered, and quietly triumphed in the privacy of an immaculately clean studio.