Continuing through April 30, 2017

In early 20th-century northern New Mexico, an circle of painters with European academic training formed the Taos Society of Artists. Starting with six artists, it grew to a dozen, including one woman. It was short-lived (1915-1927) but influential not only in establishing Taos as an arts center, but also in popularizing depictions of Southwestern landscapes and Native American peoples — subjects which became part of mainstream American art of that time. Their paintings were often reproduced for calendars distributed at railway offices as part of a marketing campaign for westward travel and immigration. Before long, Taos Society shows traveled to the East Coast, the Midwest and California. Various factors, including a lagging demand for such subject matter, led to the Society’s dissolution. But works by Oscar E. Berninghaus, E. Irving Couse, Ernest L. Blumenschein and others in the Society continue to be revered in Western art collections.

This comprehensive exhibition encompasses all 12 Taos Society artists, as well as seven associate members. It journeys deep into the roots of Western art, while paying homage to its wide scope. Short biographies of each artist are posted along with descriptions of their aesthetic points of view. There are 80 paintings in all, some rarely seen publicly, amassed from collectors and institutions across the country.

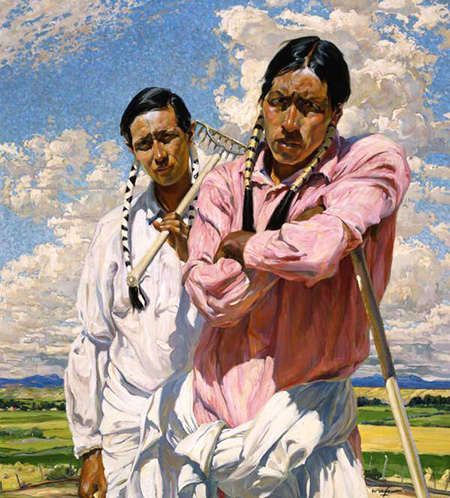

The show is at its most revealing when it sheds light on the artists’ divergence in the depiction of Native Americans. On one hand, Joseph H. Sharp’s paintings reveal his desire to nobly and ceremoniously document what he perceived as a disappearing way of life. “Broken Bow” (c. 1912) records a bare-chested man seemingly passing down his knowledge of bows to a child; both are traditionally dressed. Walter Ufer’s paintings, on the other show an affinity for the daily life of his subjects. In the remarkable “Me & Him” (1918), Ufer depicts himself with braided hair and dresses like his Taos Pueblo friend Juan Mirabal. He then poses the two of them aggressively in the foreground facing the viewer. Posed against puffy clouds and a blue sky, they appear to be taking a break from farm work.

Among other artists, however, the sense is that the Native American subjects are exotic and should be idealized. In “Relics of His Ancestors” (1913) by Bert G. Phillips, a man in traditional dress poses on the floor, contemplating the Native pottery — both intact and in shards — that surrounds him. In describing the piece, the wall text reads that the Taos Society artists were “at once respectful of indigenous traditions and history, while imposing a regard for anthropological inquiry onto their subjects where it did not necessarily exist.”

Given their association, the diverse painting styles here are noteworthy. For instance, the eye-catching “Homeward Bound” (1933-34) by E. Martin Hennings, showing two Native American figures in a winter scene, is considered a prime example of Jugendstil (German Art Nouveau) style. Meanwhile, B.J.O. Nordfeldt, an associate member, turns to Post-Impressionism for “Thunder Dance, aka The Pinon Dance” (c. 1919). With thick brushstrokes, it depicts a cluster of men in a tribal dance at the San Ildefonso Pueblo, with the sacred Black Mountain as the backdrop. “Indian Composition” (c. 1937) by Victor Higgins adds to the variety with its tight focus on a Native American woman reclining in the nude on a partially abstracted striped rug. As a curator’s note explains, Higgins pairs cubist patterns with a slightly modified Beaux-Arts pictorial style.

The many Southwestern landscapes on view are lovely reminders of what drew these painters to Taos in the first place. The artists alluringly capture red mesas, blue skies, dusty canyons and shimmering aspen groves — with and without human subjects, but all bearing a certain quality of light and drama. As such, their work helped foster a continuing romance with the great American West.