The very concept of "Love Trumps Hate" has been advocated through art for decades and now, more than ever, we need to get this kind of art out there again, especially in rural areas. During the tumultuous political climate of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam years, the visual arts played a crucial role in preserving hope and optimism in the face of the hatred, fear, and uncertainty associated with racism and war.

Not surprisingly, the 1960s produced several artists who gave physical form to ideas about universal love as opposed to the purely physical kind. The most prominent example was Robert Indiana, who was based in New York at the time and whose “LOVE" image eventually found its way onto a U.S. postage stamp. Over the years, Indiana's iconic logo has been translated into other languages and, through the widespread popularity of the artist's sculptures and paintings, it remains a strong presence around the world. Additionally, Indiana's compositional format has been appropriated and modified by various artists for worthy causes, the most notable being to address the AIDS epidemic. The Indiana-inspired AIDS logo introduced by General Idea in the 1980s undoubtedly contributed to raising awareness of the health crisis during the years when the U.S. government was not yet paying attention.

On the West Coast, while Indiana was promoting universal love in the East, Wallace Berman coined the mantra "ART is LOVE is GOD" and, as I have noted in previous essays on Berman, his message and the form through which he communicated it were prophetic and remain especially relevant today. His grids of photographic symbols predicted the way we would communicate in the 21st century, through clickable icons and insertable emojis. In juxtaposing media images that included references to different world religions, he called for unity through diversity, which of course is the very antithesis of Trumpism and the current Republican ideology.

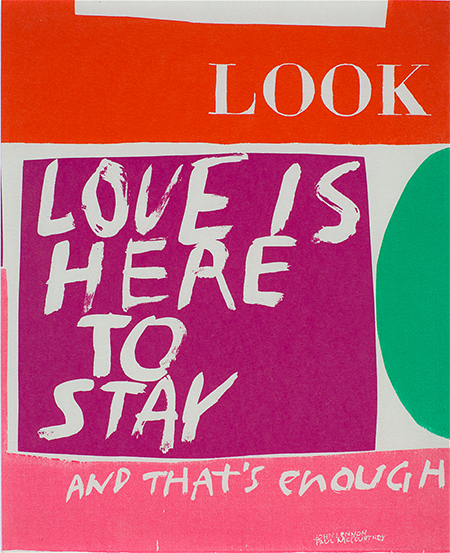

Also in Los Angeles during the same period, George Herms and Sister Corita Kent shared Berman's message. Since 1957 Herms has always stamped each of his art works with his signature logo 'LOVƎ' ('LOVE' with a reversed 'E'), meaning that love should recycle itself upon love. Kent participated in the antiwar movement in a significant way through printmaking. For one of her early serigraphs, “Look" (1965), she appropriated and changed the color of the Look magazine masthead, turning it into an instructional heads-up to pay attention to the message that fills the rest of the composition. Superimposed over a field of abstract geometric shapes that mimics the color field paintings of the day, Sister Kent's message is precise and clear: "Love is here to stay and that's enough."

Kent and the others, of course, were not working in a vacuum. They were clearly in tune with the zeitgeist that spawned the ongoing proselytizing for peace by the Beatles (the names Lennon and McCourtney [sic] appear on Kent’s print), who reminded us over and over again that "All you need is love … and in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make." It is encouraging that Kent is receiving her due here and elsewhere, as she recently had major retrospective exhibitions at The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, The Andy Warhol Museum of Art, and the Harvard Art Museums.

In more recent years, artistic advocacy for universal love, or "universal oneness," as I like to call it, seems to have played out in a more subtle fashion. The idea that we should love each other, love our planet, love our universe, and strive to get along seems to be more implicit than explicit in the multitudes of contemporary artworks that put forth pleas for social justice, remind us of the need to preserve the environment, or reaffirm our connections to one another and to the universe at large.

A great example, and a most noble recent effort to showcase art that embodies these ideas, was the exhibition "The Missing Peace: Artists Consider the Dalai Lama." A collaboration between the Committee of 100 for Tibet and the Dalai Lama Foundation, the exhibition toured from 2009-11, with the final stop being the San Antonio Museum of Art, where I oversaw its implementation. With works by 88 artists from around the world, including Marina Abramovic, El Anatsui, Laurie Anderson, Jim Hodges, Anish Kapoor and Bill Viola, it was a compelling and forceful exhibition. Yet, in my role as a museum educator, I found that most of the art still needed a guide to assist in making the meaning of the artworks more accessible to its audience.

While there is still a space for enjoying art with veiled or ambiguous meanings, which can help heal our pain via intellectual and aesthetic stimuli, now is a time for artists to once again become more direct with their messages. In looking at online photos of the multitudes of posters that filled streets and plazas around the world during the Women's March of January 21st, I was reminded of the prints of Sister Corita Kent. With a second march scheduled for April 15, there appears to be a momentum growing towards a politicially energized cultural imperative.