The social and political underpinnings of modern design may be traced as far back as William Morris, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and the Bauhaus. After World War II, however, interest shifted from European centers to Denmark, Sweden and Finland. The sparkling exhibition, "Marimekko, with Love" was organized by the Textile Museum of Canada and continues through July 9 at the Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle. Curator Shauna McCabe has gathered up all the strands to explain such influences via their fabrics and clothing designs, now available in 40 countries.

When the war ended, Finland had a $9 million war debt with no way of paying it other than selling natural resources to the Soviet Union. Stuck with the German occupation after the Finns requested Nazi help to repulse the Russians during the war, they later found themselves fending off Soviet occupation which, like Austria, they very narrowly averted.

Textile mills founded in Finland by the Scottish firm Finlayson offered another export possibility to pay war debts. In 1949, Viljo Ratia bought an oilcloth-printing company, Printex, and, with his wife Armi Antti Ainamo, soon turned the firm into Marimekko — “Mary’s dress” in Finnish — which became a global export goldmine. As McCabe notes, it embodied “an encompassing design philosophy with a democratic impulse and potential for social change.” Armi Ratia (1912-1979) became the presiding genius whose management philosophy was to find simpatico designers and give them their freedom. It proved to be a winning strategy, just at the time when women were becoming tired of the tight, restricting fashions of the 1950s, including Dior’s “New Look.” Rather, drawing from nature as “the company’s main symbolic influence,” Ratia’s people produced boldly colored, hand-silkscreened cottons and wools made into comfortable, brightly colored, and practical garments that were already of a piece with the older Finnish design tradition of peasant clothing. The combination jolted and attracted the rest of the world.

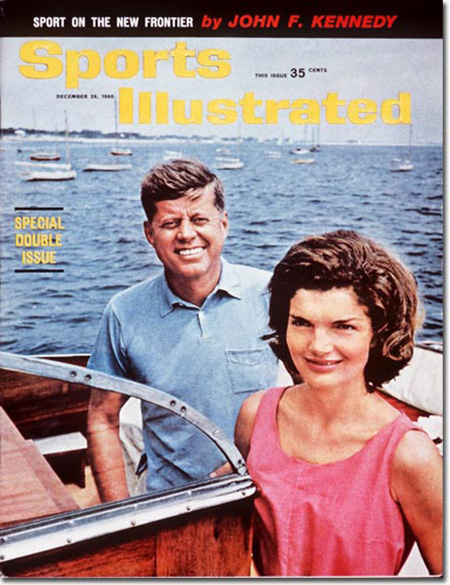

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy appeared on the cover of “Sports Illustrated” in 1960 with the President on their yacht, the Honey Fitz, wearing a solid pink sheath, one of six Marimekko dresses she bought at Design Research or D/R, founded in 1953 by architect Benjamin Thompson in Cambridge, Massachusetts, expressly to sell the new design products from Scandinavia. Jackie’s imprimatur immediately gave the company global credibility, with stores opening in Toronto in 1959 and Vancouver, British Columbia in 1973.

D/R has been called the “original lifestyle store” and Marimekko, with its range of sheets and garments as well as “shirts, candles, trays, bags, glasses, slippers, blankets and toys” created an instantly appealing aesthetic drawn from nature but expressed in curves, circles, stripes and diamonds that established the company’s brand identity from Helsinki to Sydney and Tokyo.

The installation of this exhibition is a marvel of elegant simplicity, with dresses suspended from the ceiling on plain hangers in a circle. Stretches of cloth are mounted in a row on walls like paintings, as well as draped in mid-air or heaped on tables, as in a high-end design shop.

“I really don’t sell clothes, I sell a way of living,” Ratia quipped, all the while, according to McCabe, literalizing Marshall McLuhan’s “global village” concept through electronic communication, interchangeable design modules, and a dazzling array of designers, mostly from Finland, like Maija Isola (hired while still a student), and from Japan, like Kasuji Wakisaka and Fujiwo Ishimoto.

Readers who were college students in the 1960s and 1970s may recall the various patterns which could act as dress material, curtain fabric, tablecloths, bedspreads, and aprons. All one needed was a sewing machine! “Crown Imperial” (1966), “Poppy” (1964) and “Marionette” (1970) use the most unlikely and unusual color combinations, such as yellow, cream, black and purple; or mustard, dark blue and brown, but feel appealing and restful. Long before Op art and Pop art, Marimekko anticipated their compositions, colors and contemporaneity.

With the pantheon of Finnish designers such as Aalto, Sarpaneva, Wirkkala and Franck working at the china and glass factories Arabia and Littala, Marimekko established a Finnish domestic sensibility of “clarity, purity and simplicity.” Among Ratia’s evolving crew, Isola (“Watermelon,” 1961) was joined by Wakisaka (“Piano”) and Ishimoto (“Flowering Rush”), drawing attention to the cultural links between Japan and Finland. Both countries share a sensitivity to wood, cloth and clay and share in a design aesthetic at Marimekko that became, according to McCabe, “a cultural phenomenon guiding the quality of living ... that [combined] aesthetics and utility within a unifying conceptual mission.”

Mary’s dress became Jackie’s dress and all that followed became hallmarks of midcentury modern design. Seen in “Marimekko, with Love,” along with the videos and documentary photographs, the designs may exude a period flavor, but they are not at all dated. Now that’s timeless design, not to mention brand identity.