"… realism doesn't merely include what one immediately sees with the eye at a given moment. One also relates it to past experience, … to feelings, ideas and … the totality of the awareness of it … By realism I don't mean realism in any photographic sense. Certainly not." — Stuart Davis

San Francisco is fortunate this summer to host three exemplary museum shows: the young Claude Monet at the Legion of Honor; and, less heralded but no less important or inspiring, or revelatory, Stuart Davis at the de Young. Davis may be less well known than the others, but his dazzling work deserves the red carpet treatment, too. Donald Judd, not someone who might be suspected of maximalist tendencies, after seeing a Davis show, suggested that an appropriate reaction might be applause: "Stuart Davis has more to do with what the United States is like than Hopper."

"In Full Swing" features some seventy-five of the artist's works, mostly oils on canvas, but also preparatory drawings and smaller paintings in gouache and casein. The show originated at the Whitney Museum last year, and is accompanied by an excellent short film tracing Davis's evolution from Ashcan-school street realism; through Cubism, which the artist encountered as an exhibiting young watercolorist at the famous 1913 Armory show, and in more concentrated form on a 1928 yearlong stay in Paris; to his mature style, dating from the 1930s, which derived from American-scene observation but transformed it utterly into joyous, electrifying visual music. Davis's ebullient syncopations of bright colors and interlocking shapes are uniquely his own (despite occasional resemblances to Picasso, Matisse, Léger, and Miró). Peter Schjeldahl characterized Davis as "a polemicist and a happy warrior for modernity as the heart's blood of what he called, invoking the nation's definitive poet, the thing Whitman felt — and I too will express it in pictures — America — the wonderful place we live in."

Occupying several meandering galleries on the museum's second floor, the works are hung for the most part chronologically (although the careful viewer will need to look at dates, as the direction of pedestrian traffic flow is not always clear). Deviating from this progression are several groupings of paintings and drawings showing Davis brilliantly reworking themes, sometimes from decades past, like a musician riffing on old standards. Jazz was one of Davis' longtime passions, beginning in his youth, when, "hep to the jive," he frequented the rough bars of Newark, and he continued to do so throughout his life.

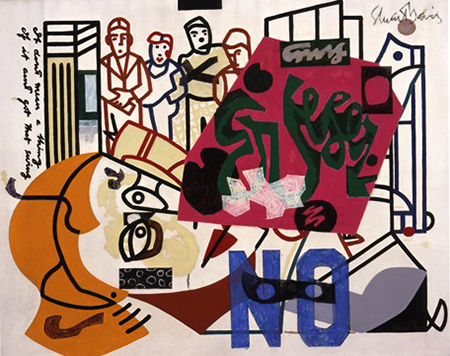

A playful but telling inscription from Duke Ellington in "American Painting" (1932/1942-54) makes this clear: "It Don't Mean a Thing if It Ain't Got That Swing." The painting also features stylized renderings of Davis and Federal Arts Project colleagues Willem deKooning, John Graham and Arshile Gorky. Gorky's cavalier attitude toward politics ended his friendship with Davis, who for a time abandoned painting for organizing, before becoming disgusted with lefty kowtowing to Stalin. Davis: "I took the business as seriously as the serious situation demanded and devoted much time to the organizational work. Gorky was less intense about it and still wanted to play." Gorky, who killed himself in 1946, when the painting was yet unfinished, may be the figure who has been canceled out.

If Davis' paintings are timeless, they are also historic windows into the art of the early twentieth century, combining aspects of Cubism, Abstract Expressionism, and, with their playful deployment of the everyday imagery of commercial America, Pop. To follow Davis' career is to recapitulate the phylogeny of American painting (except for Surrealism, which had no appeal to this son of artists, high-school dropout and student of real life). Davis died in 1964 at the age of seventy-one, of a stroke. His final, unfinished painting is here, still bearing the masking tape that he used to achieve the crisp lines that contrast so well with his pastry-chef paint surfaces. Its title, "Fin," or End, inspired by a French movie's final frame, is the last thing Davis painted.

Holland Cotter wrote: "What Davis got right was belief: the belief that he was doing the one sure, positive thing he could do, and that he would keep doing it, no matter what, in failure or success, in sickness or in health. That's the lesson young artists can take away from his show ..." In our faithless, feckless times, governed by academic learned helplessness and commercially induced moral slackness, these are lessons worth learning or relearning.