While driving in my Los Angeles neighborhood, I recently spotted a Robbie Conal poster pasted on a utility box at the corner of an intersection governed by a traffic light. The poster, "Hammer & Pickle," features an image of an angry Trump pointing his finger at us with his mouth wide open, while wearing a Russian ushanka hat that features the hammer & sickle emblem.

For most, observing the poster — if it is seen at all — is a drive-by experience, although pedestrians walking dogs in this residential area are likely to encounter it as well. And whether by car or on foot, someone else did react to the poster. When I went back on foot two weeks later to inspect it more carefully, it had been defaced, with portions of it scratched out. It is hard to know if the scratcher objected to an image mocking Trump, detested seeing any image of Trump, or simply did not relish the idea of the neighborhood being postered.

In the current zeitgeist, where previously unthinkable actions are occurring in America on an almost daily basis, there is clearly a need for political artists to be active and visible. Conal, who has a distinguished track record at guerrilla-style postering, is one of the best. During the 1980s, it was not uncommon to find his political posters in pedestrian areas such as New York's SoHo, which was a gallery epicenter at the time, along walkable sections of arts-oriented Venice Beach, or on the streets of urban Chicago, where the actors Joan and John Cusack assisted him in posting his memorable series "Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll" (1989), satirizing the George H. W. Bush administration. Three portraits included a prune-faced John Tower and the word 'sex' (Tower was involved in sex scandals), Bush himself with the word 'drugs' (in reference to the President's denying knowledge of Manuel Noriega's drug deals), and Lee Atwater with the words 'rock & roll' (he was the RNC Chairman who moonlighted as a rock & roll guitarist).

Although political postering can be ubiquitous in pedestrian areas, what sets Conal's apart from most work in this genre is that his draftsmanship is masterful and his riveting images would hold their own if they were to be presented within a gallery context. Having earned a BFA in 1969 from the San Francisco Art Institute and an MFA in 1978 from Stanford University, Conal is obviously well versed in the Bay Area Figurative School traditions, although his usual approach — which is to create wrinkled caricatures with rotting flesh that brings to mind the corroded face of Oscar Wilde's imagined portrait of the despicable Dorian Gray — aligns him with an art historical lineage that includes such notable artists/political satirists as William Hogarth, Honoré Daumier and George Grosz.

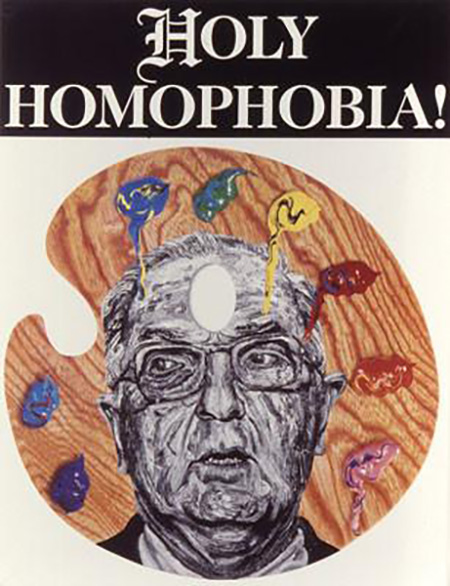

Additionally, Conal's use of language is every bit as precise and effective as in works by those who are better known than he is as political text artists within the contemporary art academy, such as Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger. Conal's lithograph "Holy Homophobia" (1990), for example, shows a prune-faced Jesse Helms in front of a painter's palette from which paint spills onto his forehead, along with the title phrase. A response to then-Senator Helms shaking up Congress over homoerotic photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, the work combines words and imagery with superb efficiency and visual potency. To this day it remains an iconic historical marker that has gained fresh relevance, considering we now have an even more extremist Congress and homophobia (along with other forms of hatred) is once more on the rise.

Another reason why Conal's prints and posters deserve wider recognition in terms of art historical relevancy is that, in addition to qualifying as fine art, their reach extends well beyond gallery walls. Recent works such as "Hammer & Pickle" and "Bully Culprit" (both featuring a prune-faced Trump) have made their way into many of the anti-Trump marches around the country, a phenomenon that is well documented on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

When political art achieves an aesthetic excellence, as Conal's does, we are all the better for it because the power of the message tends to be longer lasting when it is presented as an artful experience that can engage and heighten our senses, linger in our visual memories, and continue to remain with us long after we have left the demonstrations.