Given the high drama of his personal life — seeing his mother die of starvation when he was a child, escaping the Armenian genocide, coming to the United States to carve out a revered niche in the tenuous wall of the New York avant-garde, then sinking into depression and committing suicide at age 44 — Arshile Gorky is ripe for a flashy Hollywood treatment with someone like the always-intense Christian Bale constructing an over-the-top portrait of the anguished artist. Because he fits so well into the crazy painter trope, it may be difficult to see past the media buzz and look — really look — at Gorky’s art. Yet those who manage to do so will be rewarded with surreal grace and intellectual insight offered by few other mid-century artists.

The literature on Gorky focuses strongly on the artist as a threshold figure, serving as a psychic conduit between the collapsing European avant-garde and the rise of American Abstract Expressionism. He is often portrayed as the liminal figure, straddling the Picasso-Miro-Matta and Pollock-de Kooning axes, and historically, he did serve that aesthetic function. But I would urge those who visit this retrospective to consider Gorky qua Gorky.

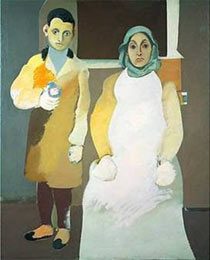

The canonical narrative begins discussion of Gorky’s oeuvre with the double portrait of the artist and his by-then starving mother, drawn from a 1912 photograph taken in Turkish Armenia. Born in 1902, Gorky fled to the United States in 1920 and worked on the double portrait from 1926 to 1936. It is uncannily similar to Picasso’s “Self Portrait” from 1906, done soon after the Spanish artist made his life-changing move to Paris. (It begs the question: How much did artists’ geographic dislocations affect the development of the avant-garde?)

Also in the late 1920s and early 1930s — when he was teaching and sharing his studio with fellow immigrants Willem de Kooning and Hans Burkhardt — Gorky produced still lifes that echoed the formal innovations of both Cezanne (“Pears, Peaches, and Pitcher,” 1928) and later Synthetic Cubism by both Picasso and Braque (“Still Life,” 1930-31).

The late 1930s changed everything, including Gorky’s painting style. After 1939, when Hitler marched across Europe, harvesting death throughout the continent, many of the avant-garde artists followed Gorky to Manhattan. Among them were the Surrealists, led by poet Andre Breton, as well as painters Max Ernst, Roberto Matta, and Yves Tanguy. Breton befriended Gorky in New York and taught him the psychoanalytical ways of Freudian dream and fantasy. Gorky abandoned representational figuration for biomorphic dreamscapes that transform the rectangular canvas from window to internal mirror. Although he continued to use comprehensible titles (“The Betrothal,” “Soft Night,” “Garden in Sochi,” etc.), Gorky’s paintings became expertly balanced overall compositions of totally abstract forms. Limned with expressive verve, they opened the door to Jackson Pollock’s overall drip works in the late 1940s.

But earlier in the decade, while Pollock was still working for the WPA Federal Arts Project, Gorky created his masterworks. Elegant and lyrical, powerfully curving pod and organ forms float over amorphous fields of color. Eschewing the primary colors Joan Miro preferred and the space-age fantasies evoked by Tanguy’s organic landscapes, Gorky presented a world of vaguely biological forms, hovering in anxious interiors, shimmering just beyond conscious recall. The shapes seem familiar but defy concrete knowing. We are compelled to shift and stutter our mental grasp. I know that, I almost recognize it…but what is it?

This is the liminal value of Gorky. Not so much the fact that he embodied the avant-garde transformation from Europe to the United States. Not so much that he opened the door between Miro and Pollock. But that he occupied — and still occupies — that place of perception that defies linguistic trapping. That place we need to go in order to know something else. Something outside. Something beyond.

Published courtesy of ArtSceneCal ©2010