Continuing through February 10, 2018

Photographer Laura Aguilar’s approach to image-making and portraiture is thought provoking. For the past 30 years she has focused her camera on herself as well as individuals and groups that many of us don’t tend to notice or think of as conventionally beautiful or inspiring. But photography for Aguilar has always been a tool for examining and perhaps becoming comfortable with her own circumstances as a weighty, queer, working class, Latinx vying with the difficult language communication issues of auditory dyslexia.

Her pictures are a way to examine and reflect upon the world around her and her place in it. This retrospective, part of the citywide Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA series of exhibitions, enables us to see some of the ways this remarkable artist developed, and continues to advance that investigation.

A self-proclaimed “mostly self-taught photographer,” Aguilar garnered critical attention in the 1990’s for her penetratingly sensitive documentation of the Chicano Lesbian community and obese people of color. But it was her nude self-portraits that most challenged established mainstream conceptions of the body, race and gender, and really pushed her own thinking forward.

Originally made to help the artist deal with the discomfort and shame she felt as an obese, lesbian woman of color, Aguilar’s nude self-portraits often probe and visualize the power differentials resonating within her life. As a reclining nude in the 1989 “Sandy’s Room” she visually references the naked prostitute in Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” that shocked the public by directly returning the viewers' gaze. Aguilar however is completely self-contained in her exposed sexuality. She reclines in front of an electric fan, instead of a ministering colored servant, head tilted back in private enjoyment of the moving air. It’s a strong proclamation of updated personal agency, turning the tables on Manet’s confronting gaze while underlining its thinly veiled racism and still entrenched male gaze.

In her often discussed nude self-portrait, “Three Eagles Flying” the artist is bound by and between a U.S. and Mexican flag. As much a rebellious statement about feelings of being forced into racial or gendered identities, it also speaks to the haunting depersonalization the artist felt trying to inhabit cultural positions where her sex or body type just didn’t fit.

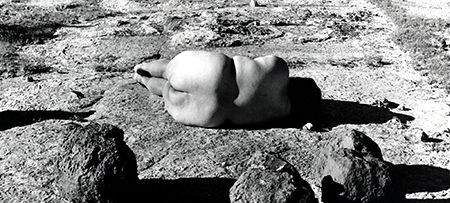

So it is not surprising that on a road trip through New Mexico in 1996 the artist let those identities slip away. Inspired by the work of Los Angeles-based photographer Judy Dater, Aguilar in her “Stillness”, “Motion” and “Grounded” series merged her body with the landscape as if reaching for something in nature that is outside stereotypes or cultural restrictions.

“Nature Self-Portrait #2" is a rich black and white study of rounded forms and deep shadows. The dark chiseled roughness of three large boulders rest in the foreground of the image, effectively cradling and contrasting with the pale, fleshy smoothness of the artist’s prone backside, which is all we can see of her. Her head is hidden in her own shadow, only her back is towards us. Pure and unadorned, all the round forms share a vast flat rocky plain and deep shadows that don’t differentiate at all between living body and stone.

The human body in these images is beautiful, and the flesh against the rocks and ground incredibly sensual. But like women’s bodies, nature too has a long history of imposed limitations and unceasing conquest. It is that reality, along with the social implications of race and gender that we glean from pieces like "Motion #56." In this image the bodies of three voluptuous women of different races cascade down a rocky hill toward the camera, their faces obscured by their hair. By mimicking the layered folds and smoothness of the rocks surrounding them they become one with the ground, with their soft flesh acting like a disquieting nudge that reminds us of the earth’s vulnerability. However their exposed physicality on the undeveloped ground also makes them a pointed metaphor for all people whose race, gender and body (or mind) is treated as being wide open for outside “development” or possession.

That’s a poignant statement about personal sovereignty and the right to freely exist that the artist makes even more personal with her autobiographical videos that are also part of this exhibition.