Continuing through February 17, 2018

Examples of early tapestries have survived from the time of the ancient Greeks. The rise of the art form though, did not occur until towards the end of the middle ages when tapestry making became synonymous with history, wealth, and power. Photographer Gary Goldberg’s new large-scale wool tapestries are transfers of architectural photographs reproducing details of the worried facades of colonial buildings in Oaxaca City, Mexico, and part of an ongoing series modestly titled “Finding the Universe in Oaxaca.” They are a captivating aesthetic statement about both the nature of representation and the union of the arts and crafts that would fulfill William Morris’ wildest dreams. Each of these monumental pieces were realized through Goldberg’s long-term collaboration with indigenous artisans at a felting workshop known as the Taller de Afelpado in San Agustin, Oaxaca.

In the transfer process a kind of cartoon derived from the photograph is used as a guide that the artisans weave into a finished tapestry. Goldberg oversees the process and makes formal changes to color and line elements that transforms the images from conventional photographs of walls into tapestries that assume an entirely different presence, taking on the form of landscapes, topographies, abstract paintings and celestial realms.

This is clearest in the cosmic “Finding the Universe in Oaxaca, blue ground blue sky low horizon.” Along the 120-inch horizontal stretch of this long rectangular tapestry is a band of night blue peppered with white spots that resemble stars in the darkness. Above this a lighter color scheme with textured formations delineating a horizon line, which resembles a terrain, perhaps a planet of some sort. This inverts the typical representational trope where the sky is above us, here its like peering at the southern pole of the moon. In addition to disrupting perspective via the horizon lines, Goldberg revels in manipulating scale; he transforms images obtained from a grounded eye-line into aerial landscapes. The final product bears only a slight resemblance to the photograph it’s based on. Through this decidedly analog process Goldberg’s pieces are at once a throwback and something that expands the possibilities of photography itself.

The vertically oriented pieces, sized at 96 inches tall, strongly channel New York School Abstraction while remaining steadfast to their particular visual mode. From the same series “floating oval on deep red ground,” Goldberg places the oval band of dark pigment in the upper section of the image. This is similar to where Adolph Gottlieb positioned the circular forms in his famous abstractions, the floating ball of paint usually in tense opposition to a flurry of brushstrokes. Goldberg lets the oval takes its place alone, interacting with the red ground, spare dark lines, and a mesh of white lines to the lower right. Where Gottlieb dealt with the nuclear age and post-war anxiety, Goldberg offers an iconic expression of calm and rich contemplative surfaces that suggest meditative states.

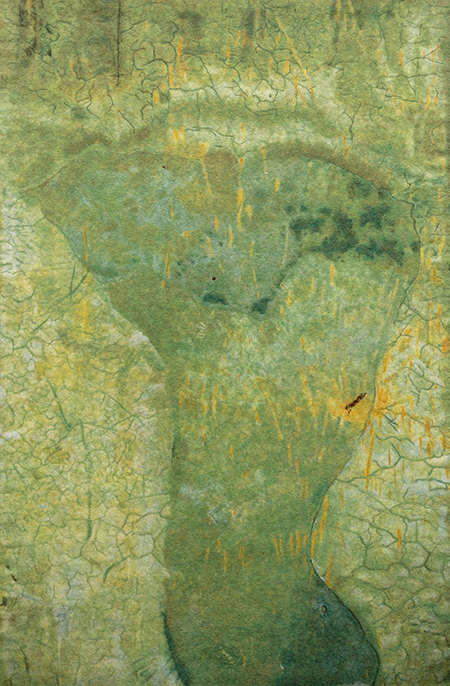

In “mujeres bellas on green ground,” another vertical abstraction, there is a hint of figuration. A whirling funnel shaped form might be an abstracted body, or else it contains them, as its extremities exit the frame to the left and below. Surrounding the figure is a lattice of interconnected and irrational shapes that provide the ground. They visually isolate the central form that seems to compete against them in order to take over the entire surface. Sedate light and dark greens comprise the color range, highlighted in part with yellow strands.

With this body of work Goldberg starts with the troubled legacy of the colonial past in one of the poorest states in Mexico. He transforms this past into a message of hope through the metaphysics of abstraction that testifies to the resilience of the people there, whose cultural traditions are some of the richest in the country, and without whom his work would remain plainly two-dimensional.