In late 1977, I was introduced for the first time to the work of Ed Moses, who died in January, some forty years later at the age of 91. That Moses exhibition, which I found visually stunning, was on view at the Margo Leavin Gallery. Although I grew up locally, I was a new arrival to the L.A. art scene, and knew relatively little of the area's local art history. I had yet to learn about Hard Edge, Finish Fetish, or Light and Space, as 20th century art history courses at Harvard focused on Europe and New York. In lectures by Michael Fried, I was injected with a heavy dose of Greenbergian formalism. The curriculum was also deeply steeped in European modernism, and I devoted an entire semester to studying the work of De Stijl's chief advocate, Theo Van Doesburg, who is best known for favoring diagonal lines over horizontal and vertical ones, in response to his compatriot Piet Mondrian's ideological preference for the latter.

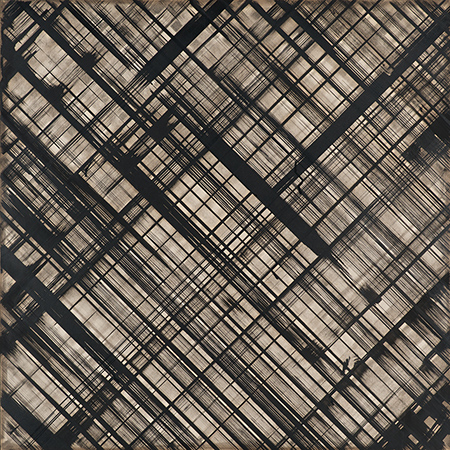

Moses' 1977 exhibition was comprised of a series he called "Cubist Drawings," which he considered to be simply diagrammatic studies for abstract paintings. In my mind, however, these compositions that I characterized in a review as "complex networks of intersecting and overlapping diagonal lines on square or rectangular fields" were every bit as powerful as any painting I had ever seen. Upon viewing them, I was immediately struck by their relationship to the work of Van Doesburg. I wrote that if the De Stijl leader were still alive, "he probably would be ecstatic," because "Moses had realized what Van Doesburg dreamed of, but never fully accomplished." What Van Doesburg envisioned was an art that could support the creation of "a new life-form which is adequate to the functioning of modern life."

The drawings that especially excited me were Moses' more open compositions done in black and white, because they were the most energetic — far more so than anything Van Doesburg had done — and they could activate a viewer's eyes into a continual movement. Moses' quieter and more minimal black on black drawings seemed paradoxical and austere, but were no less effective.

In hindsight, when we examine Moses' career that spanned seven decades, it seems that the "Cubist Drawings" series is in certain respects a microcosm of the artist's oeuvre as a whole. Although the series is restricted to one particular motif, Moses examined it exhaustively and pursued multiple avenues for color, density, and compositional structure. In contrast to Van Doesburg, who was steadfastly devoted to a single style that he kept very minimal, leaving little room for even subtle variations, Moses was always evolving. While never abandoning his commitment to abstraction, he was a dedicated, restless, and adventurous painter who consistently found new ways to explore abstract painting's never-ending possibilities, whether it be in terms of style, medium, or composition. He even boasted with pride, in a 2014 video produced by The Artist Profile Archive that one of his favorite mediums for painting was "Jack's Secret Sauce," available at your local Jack in the Box eatery.

At the time I engaged Moses' "Cubist Drawings," most L.A. artists were still feeling like second class citizens in the eyes of a New York centric art world. Although such perceptions about the L.A. art scene have been largely disproven through the successes of the recent Pacific Standard Time and Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA projects, it was the work of Ed Moses that convinced me forty years ago that the elitist East Coast attitude was nothing more than bullshit. I am indebted to Moses for being the very the first artist, in Los Angeles and elsewhere, to show me that really great art can be found anywhere.