Apocalypse, disaster, holocaust — the ways in which the creative arts confront our species' darkest hours are manifold. In "Dr. Strangelove," film director Stanley Kubrick trained his lens on nuclear armageddon in a mode of high satire and gallows humor. In "Mount St. Helens Symphony," composer Alan Hovhaness used the volcano's 1980 eruption to paint a soundscape of unimaginable violence. Once glimpsed, it is hard to forget artist Anselm Kiefer's paintings and sculptural installations, the best-known of which turn historic Nazi atrocities into vehicles for harrowing pathos. As I noted earlier this month in a recommendation of Henk Pander's drawings at Augen Gallery, images of annihilation have taken on fresh urgency now that a petulant hothead sits at the Resolute desk, pondering which dictators to provoke and which to emulate.

Pander's syntax of skulls and skeletons, burning buildings and ships, forlorn souls wandering the ruins of civilization, seems less melodramatic and more cautionary than it did during more even-keeled administrations. Our current predicament has led me recently to revisit one of Pander's best-known images, "The Bombardier" (2003), in which a fighter pilot turns from his cockpit controls to stare down the viewer. The angle is extreme, the city burns below, and one wonders whether the plane is plummeting earthward on a suicide mission, or if the pilot is merely pausing to pose, delighted at the devastation he has wrought. Either way, it's a chilling vision, abjectly nihilistic and in my view morally problematical. It is a worldview without hope. I'm reminded of a 2005 review Roger Ebert penned about the horror film "Chaos." "The movie," Ebert held, "denies not only the value of life, but the possibility of hope." I believe it's especially important today, both in aesthetic projection and political action, to point a way forward that admits hope even in the direst of times.

Two exhibitions that consider apocalypse but manage to find silver linings (if that's possible) stand out in my mind. One I saw ten years ago in Portland's now-defunct Launch Pad Gallery. In a suite of mixed-media drawings entitled "A Swansong, A Love Letter, A Blanket" artist Rocky Cohen (aka Rochelle Koivunen Darensbourg) posited a post-catastrophe society in which survivors are forced to return to a pre-industrial paradigm and live more in harmony with plants and animals. Having lost the trappings of the digital age, humankind returns to communion with sea creatures and flora, whose tentacles and root systems enfold and embrace us as cousins sharing the planet. It is apocalypse envisioned through rose-colored glasses: chipperly granola and wholly un-ironic. Some may have found the work precious; I found it refreshing.

The second show, which I viewed last month at LSH Gallery in Los Angeles, was devoted to paintings on paper by Senon Williams. Entitled "Banned Together," the exhibition included many images from Williams' book, "Hunted & Gathered", published late last year by Hamilton Press, the art-book love child of Ed Hamilton and Ed Ruscha. The paintings take on the ugliest quadrants of the human soul in a scorched-earth environment of eat-or-be-eaten social Darwinism. Above an image of presumably the last two living people in the world, a caption asks: "Will the last two fight?" The phrase "A natural tenderness in humanity" illustrates a man wielding a knife that drips with blood, walking away from the person he has just murdered.

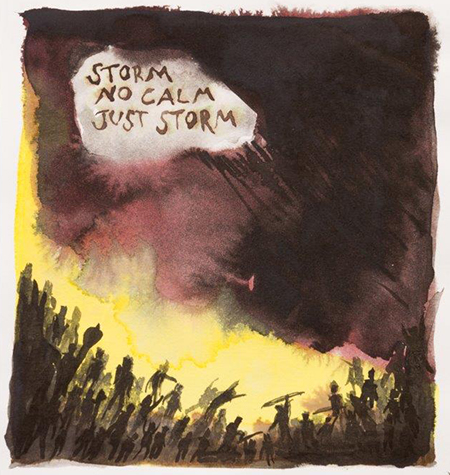

Certain pieces are practically slogans for Donald Trump's America: "Storm. No Calm, Just Storm." "Man, Did the Tide Turn." But Williams, like novelist Cormac McCarthy in "The Road," superimposes the possibility of dignity and integrity above the grimmest aspects of our natures. Once in a while, amid the 129 vignettes in "Hunted & Gathered," Williams sprinkles in reassuring images of gentleness and kindness, all the more striking for their incongruity. A figure striving to escape a mob is captioned: "The Beauty of Life is Because we Fight So Hard." Two figures embracing one another are described simply and heartbreakingly: "They were friends." And a brightly-hued abstract composition, in a departure from the book's predominantly somber tones, reads: "There is So Much Life in Here." Yes, there is. Solace, redemption, tenderness are hiding in plain sight. Nihilism doesn't have to win the Manichean duel. The good guys might just win, if only for long enough to savor a sunset, a meal, or a loved one's smile before the chaos resumes.