Continuing through April 21, 2018

The titular painting of “Dark Light” describes a single figure, bathed in a ghastly yellow-green light and wearing his battle camouflage, standing in the bed of a red pick-up truck. His right arm extended, one swollen hand grasps a flashlight that directs a solid cone of light beyond the left edge of the canvas. We will never know what that light is illuminating, nor will three sleeping figures sharing the truck bed ever care. The truck’s color is complemented by the standing figure’s red hat, so we know that we are on a journey into Trump’s America. So it is little wonder that the formal space is flat enough to break your nose, even if we know we are looking at distant mountains and a night sky. A silver cylinder vertically bisects the composition, spewing forth an enveloping dark smoke. The deep cobalt moon takes its cue from Edvard Munch’s “Moon Light” (1895), that orb’s yellow reflection a thrusting bar of light, inverting it into a dark pouring of oil.

If one image I’ve seen in the last 18 months sums up both the narrative and feeling of being shockingly trapped in an unremittingly vulgar world marching towards a willfully disastrous end game, this might be the one. The image is extremely vivid, its formal structure so severe as to be a waking nightmare. If we are not at a loss for modern day Jeremiahs prophesying that we are inviting our own demise, and Eisenman is certainly among them.

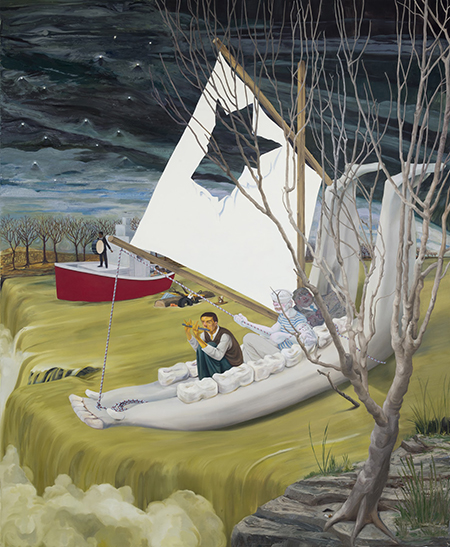

That our history has taken a decidedly dangerous wrong turn is also the central point of “Going Down River of the USS J-Bone of an Ass.” A Biblical reference is once again taken up to express a decidedly un-religious American moment. The seated man plays his flute as his jaw-bone vessel sailing on a river of sludge is about to go over the falls. Another vessel similarly approaches disaster as an African American man bangs a drum. The crown of a tree in the foreground would obscure the boat, but it as barren as the forest on the opposite bank. And what is that shape cut out of the white sail of surrender? A head of Cerberus no doubt. The fingerprints of George Grosz and Max Beckmann are all over this, suggesting that we are in store for an unwelcome trip back to the 1930s.

Just in case you mistakenly liken these paintings to “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” Eisenman has recreated (based on her exhibition in Vienna last year) a sculptural installation she ironically calls “Monument to a Politician.” A suite of white office furniture, complete with a pair of potted plants, is spoiled by a rough wood construction that rises towards the ceiling, topped by what feels like a decapitated head, covered in black paint/blood that has rained down, soiling the furniture below.

Emotional neutrality of the participants painted into these central works adds up to passive compliance and moral bankruptcy. Accompanying are small works and studies that lend nuance that otherwise is lacking in the larger works. While somewhat leavened by details like a squirrel hilariously paddling downstream in “Dark Light,” Eisenman seems perfectly content to harangue us right back out onto the street, where encountering a homeless encampment may feel like something of a relief. “Onanist Own’n It” is a jerk-off painting on paper whose aging bald protagonist is so very proud to ejaculate. “The Shooter” is her second amendment buddy who has been popping up a lot, probably so that we may enjoy staring down the barrel of his gun. Faces smoke, blow snot and generally expose the baseness of their corrupt humanity without the slightest hint of shame. The supplementary drawings show Eisenman to be a serious draftsman whose polemics are situated on a solid foundation. She has always been a good stylist, capable of moving from chaotic expression to carefully calibrated formalism with the gracefulness of a professional dancer. When you look at a bagatelle of a pencil study for “Dark Light” in which the pick-up truck is still a riverboat, and you see a face emerge that Matisse or Alexej von Jawlensky would have been pleased to execute, you end up coming away at least somewhat reassured, if not smiling to yourself that Eisenman does, after all, possess this pathway to joy. You feel happy for her. It’s right there in the seeing and the making, and that is what will save both her and us.