"Why does one paint or sculpt? Nobody knows the reason … One does it out of madness, out of obsession, out of a more automatic than conscious need... I have always failed. — If only I could draw! — I can't. That's why I keep on drawing…" — Alberto Giacometti

Traditional biopics of artists tend to be both entertaining and pompous, allowing middle-class audiences the vicarious pleasures of Bohemian excess; of shaking our heads at the benighted art audience of the past; and of ascending with the art-martyr (Vincent, Frida, Jackson) into cultural immortality. I like them, in general, and think they help build the case for an artist's serious work.

The new film "Final Portrait," written and directed by Stanley Tucci, wisely takes the path of simplification and compression. This was aided by its source material, "A Giacometti Portrait," the 68-page memoir (written for a magazine, but published in book form in 1980), by James Lord. Lord was a then young American writer who became friends with the Swiss-Italian sculptor and painter in Paris and consented to pose for him. Fortunately for us, what was intended to have been a simple oil sketch that would require, in Lord's words, "but an hour or two, an afternoon at most" grew into a project that consumed the eccentric genius artist, ultimately requiring eighteen sessions from September 12, 1964, to September 29, before Lord's deadline date, his return to New York having been postponed several times.

His reward was not just a valuable painting and token of his friendship with the famous artist, but also, through his covert note-taking, a day-by-day journal of the vicissitudes of the creative process. Alternating between Giacometti's ferocious drive to work and the creative destructions which he felt powerless to control, the artist's mood was marked by interludes of despair and self-doubt. He at times "exuded gloom." Having just reread the book, I now see what an ideal collaborator Lord was for Giacometti: both curious and extraordinarily patient, especially for a "youngish" (his term) man. Others might not have endured the dramatics: in 1935, when Giacometti despaired of being able to paint or sculpt a head, André Breton said, with the exasperation one would not have expected from the Pope of Surrealism, "Everybody knows perfectly well what a head is."

Well, not everybody. Matti Megged, in "Dialogue in the Void: Beckett & Giacometti," summarizes a story that the young Giacometti wrote about the feelings of dislocation and panic that sometimes afflicted him. Objects appeared to him to have lost their normal roles in the universe, and become infused with mystery; in Giacometti's words, "both living and dead at the same time," and "suspended in a dreadful silence."

Art historian Peter Selz verified that this sense of alienation persisted: "Everyone before him in the whole history of art had always represented the figure as it is; his task now was to break down tradition and come to grips with the optical phenomenon of reality. What is the relationship of the figure to the enveloping space, of man to the void, even of being to nothingness?"

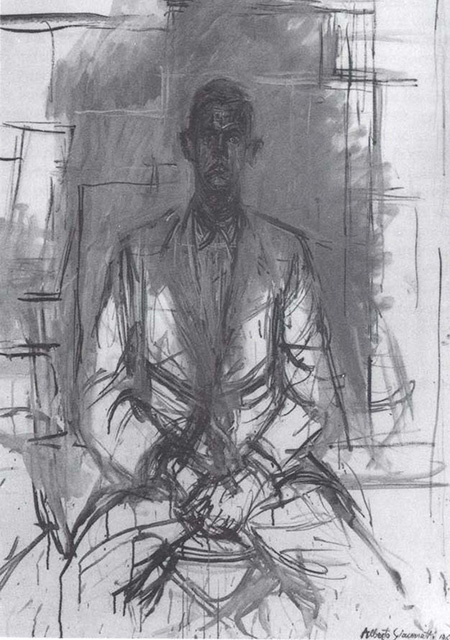

In "A Giacometti Portrait" Lord describes with admirable composure what might have driven many to despair, the heroic but foredoomed grasp for the unattainable. Giacometti paints (in black and white with fine pointed sable brushes) and unpaints (in gray, which, for him, contained all colors, with a medium-sized round brush) Lord's portrait innumerable times over the eighteen-day process. Giacometti's wife and sometimes model, Annette stoically advised: "You'll get used to it."

As Lord's last day of modeling approaches, he devises a stratagem to forestall yet another collapse of his portrait into entropy:

"…after a time he began to use the large brush with white, painting the area around the head and shoulders and finally part of the face, too. This led me to infer that little by little he was painting out what he had previously done, undoing it, as he said. Presently he took one of the fine brushes again and began to paint with black, concentrating on the head. He was constructing it all over again from nothing, … when the moment I had foreseen came, I said, "I'm very tired. Do you mind if I have a little rest?… I stood up, went behind him, and looked at the painting. It was superb. The awkward vagueness of 45 minutes before had completely disappeared. I said, "It looks fine. Why not leave it as it is now?"… He's sighed… "Well," he said, "we've gone far. We could have gone further still, but we have gone far. It's only the beginning of what it could be. But that's something, anyway."

I have gone on in some detail about the Giacometti-Lord collaboration because Tucci's movie adheres so faithfully to the book, and therefore evinces both its virtues and faults. The acting, lead by Geoffrey Rush as Giacometti and Armie Hammer at Lord is superlative, even if the characters are not given much to do, plot-wise. Tucci's command of tone and pacing are all that could be desired with what is essentially a two-man play. James Merifield's set, which replicates Giacometti's famous, much-photographed studio at 46 rue Hippolyte-Maindron, becomes itself another character: dusty and disheveled, black, gray and earthen colored, it's an exudation of its chain-smoking, muttering tenant from 1928 to 1965, a nest shaped by its odd bird. The music, by Evan Lurie, is sprightly, insouciant, and French, comme il faut.

When Giacometti asks on Day 6 if the process was "getting on your nerves," Lord protests that "the entire experience was an exhilarating one." By day 15, as the project wound down, Lord "tried to tell him what a wonderful experience posing for him had been and how much I had appreciated his letting me do it." Replies the artist, "Are you completely nuts?" For the knowledgable viewer "Final Portrait" is light-hearted and drily humorous, but deeply respectful, emotionally moving and exhilarating. If you are instead a casual artster you may, echoing Giacometti, come away feeling that the film was just nuts.