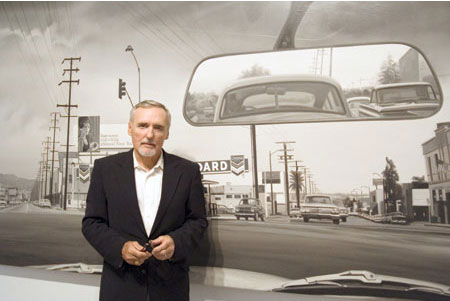

Double Standard

1961/2006, water based primer oil and matte varnish on vinyl

9' 5" x 14' 2"

Photo of Dennis Hopper by Joel H. Mark, 2006

Dennis Hopper (1936-2010) played many roles in his turbulent life, and from numerous descriptions, the toughest proved to be himself. Whether channeling the self-destructiveness of his close friend, fellow cinematic "Giant" and "Rebel Without A Cause" James Dean with his own frenetic excesses, or channeling his demons to create such haunting characters as Frank Booth in David Lynch's "Blue Velvet," Hopper often seemed to embody an almost maniacal, rebellious spirit. Yet by the time of his death of prostate cancer, on May 29, at the age of 74, Hopper had lived long enough to see himself acclaimed as an elder statesman of sorts.

If to the general public, he was best-known as a colorful, maverick actor-director, to the art world he wore other hyphens, as a highly engaged, and at times prolific, photographer-painter-collector-observer and general devotee. At the heart of his legacy is his role in documenting the Los Angeles (and New York) art world of the 1960s. However tumultuous his own life may have been, behind the camera Hopper evinced the control, intelligence, self-restraint and dry wit of an astute observer. His photographs of the 1960s, of such notable art world denizens as Ed Ruscha, Ed Kienholz, Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, Craig Kauffman, Billy Al Bengston, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, gallerist Virginia Dwan, curator Walter Hopps, and others, bear eloquent witness both to Hopper's own talent and to the burgeoning artistic subculture which inspired him. More often than not these subjects were his friends, and these photographs reflect both his comfort with them and his understanding of their craft. Taken largely with the Nikon camera that his first wife, Brooke Hayward, bought him in 1961 for his 25th birthday, the images capture many of these figures before the peak of their fame, as ambitious young up-and-comers. Often, they are seen framed drolly against the galleries, studios, or streetfronts they inhabited in ways that seem to reflect back on their subjects' own self-image.

An ardent art collector, he started buying Pop Art when it still seemed experimental or even absurd, and one could buy a Warhol soup can painting for little more than the can itself. Between the ups and downs of his Hollywood career, he continued to make art: his color photographs of graffiti were another way of bringing the streetlife of Los Angeles (and more exotic locales) into the gallery, as he had done with the billboards he photographed earlier.

In 2006, his iconic 1961 photograph Double Standard--which shows the intersection of Doheny, Melrose, and Santa Monica Boulevard as seen from the front seat of a car--was chosen as the poster for the landmark exhibition at the Pompidou Center in Paris, "Los Angeles 1955-1985: Birth of an Artistic Capital." Meanwhile, he returned to the canvas--or rather, vinyl--crafting large billboard-style paintings derived from his early B&W photos, a body of work which was presented that same year in a sprawling show at ACE Gallery (Hopper's photographs have been exhibited in recent years at the Craig Krull Gallery in Santa Monica).

This summer, the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA will present a comprehensive survey of Hopper's artwork, titled "Dennis Hopper Double Standard." Running from July 11 Ð September 26, 2010, the exhibition is the first show generated by incoming MOCA Director Jeffrey Deitch, and has been assembled in a matter of months (which in itself feels like an homage to the artist in its screw-the-rules guerilla spirit). Curating the show is painter-filmmaker Julian Schnabel, who directed Hopper in 1996's "Basquiat," along with curatorial consultant Fred Hoffman. It promises to be a controversial show, with some questioning Hopper's greater historical significance; but it is also clearly a feel-good show, in giving Hopper--who spent much of his recent decades between Taos, NM and his expanding Venice, CA, compound, designed by Frank Gehry--his ultimate due as an art world insider, and an artist in his own right.

While he didn't live to see the show, Hopper did live long enough to enjoy his status as an art world elder statesman. The following excerpts are from an interview with Hopper in 2006, during his ACE retrospective. Surrounded by his work, looking back into the rear-view mirror of his career, he seemed utterly engaging and engaged--and very much in his element.

GM: Could you talk a little about the difference between painting and photography for you? Because some of your paintings are based on your photographs.

DH: Well, it's weird because I've always thought of the photographs as paintings. The ones that I did flat on, so that they had a painting surface, they had no depth of field, I've always thought of them as paintings. I mean, they were things that I would have liked to have painted. Because when I came to abstract expressionism and action painting, I realized that the emotion that's coming from inside is basically almost all an abstraction of things you could find in reality, it's all around us ... Los Angeles to me has always been cars and billboards and graffiti. That's what I see ... If you really look at Los Angeles, it's not a very visual city. It feels like everything's been built for the next earthquake to take it down. Yet I've lived here most of my life. I love the billboards. I've loved them from the beginning. I took Rosenquist down in '63, Henry Geldzahler, I used to take everyone to see billboards. I wanted to buy this one with Brooklyn Gas, which is in Double Standard; it was $750, oil on wood, all I had to do was replace the wood and they'd give it to me. It would've been great! So finally, I came to a conclusion that there are only so many images that can possibly last, in my opinion. I thought, there are certain images I feel really strongly about. And there are certain people I feel really strongly about. And I think that to make billboards out of them, and to put them back into oil, is--a reflection of where I've been. And what I've seen. The graffiti is a whole other thing, it came out of Colors.

GM: I love those graffiti photos, because it feels like it's somehow between painting and photography, between found and made.

DH: It also lets me be an action painter. (laughs) When I came to the scene, in 1954, I went to Vincent Price's house, and--I was already doing abstract work by the way, but I thought I was just fucking around--and I walked in and I saw Diebenkorns, Franz Kline, Emerson Woelffer, Motherwell, this little Jackson Pollock. And I was like 'Wow! It's okay!' And I went into it. From '54 to '61, I was painting like crazy. Then I lost everything in the Bel Air fire in 1961.

G/M: Did you know those other artists at that point?

DH: Oh, yeah. I met Walter Hopps, Ed Kienholz, George Herms, and Wallace Berman. Bob Alexander. They had a place called Stone Brothers Printers; I got there in 1955.

GM: I guess the story was that you met them through James Dean.

DH: Yeah. There was a street performer, I think his name was Mr. Chang. He was an Oriental guy, he wore a Confederate uniform, he was on Hollywood Boulevard, and he put his hat down and he did Shakespeare. Jimmy loved him, thought he was great. So we were meeting at this place down across from the Veteran's Hospital, and I just started hanging with them.

GM: Was Barney's Beanery a scene by then?

DH: That started a little later, with the Ferus Gallery, when everyone moved to La Cienega. Walter always used to say we did it over a stale hot dog at Pink's, made the deal for the original Ferus. Then Wallace got busted for pornography, I think that was around '57. Dean Stockwell had to bail him out. Dean Stockwell and I, and Russ Tamblyn, were really the only guys around that sort of scene.

GM: It seems that one way that Pop Art overlaps Hollywood is in the attraction to the idea of how something becomes a memorable image. The translation of ordinary life into these icons that you recognize. You were so tied in to that zeitgeist: the way Warhol used iconography, and Ed Ruscha with this very flat graphic view of this landscape ...

DH: Absolutely, yeah. It was really fascinating. There always seems to be about twelve people, in all these movements ... they don't happen because everybody just decides, oh, let's paint abstract one day, you know, they come from here, and here, and here, and they all realize that they're doing abstract work. And Pop Art was the same way.

GM: When you saw that first Warhol's soup can, you were very excited.

DH: Right, because everyone was talking about the return to reality. We were now third generation abstract expressionists, you know. Everybody said 'Where is the return to reality? Where is the return to reality out of abstraction?' So when I walked in, and Irving Blum showed me ... a soup can by Andy, he showed me a comic book by Roy Lichtenstein, he showed me a light bulb by Jasper Johns, and that paint can with all the brushes in it, all out of bronze. And I said 'That's it! That's the return to reality!' And he said 'What are you doing tomorrow?' And I said 'Nothing.' And he said 'Well, we're going to New York.' So Irving and I got on a plane and flew to New York, and I went to all the studios. And that's when I photographed Roy sitting on the floor and every famous piece was there. I bought a--I was at Paris, for the show at the Pompidou, of LA Art from 1955-85, and I came back to the hotel, and opened up the paper, and there was the painting I used to own, called The Sinking Sun by Roy Lichtenstein. The guy was putting the hammer down at Sotheby's. And it went for $15,690,000. And I paid $1,100 for it! (laughs) My wife got in a divorce and she sold it back to Irving Blum for $3,000. She thought she made a really good deal. (laughs)

GM: So back to the Warhol...

DH: Andy's show was out here, as you know, the soup cans. Irving says I bought mine out of his show. I don't believe that. I bought mine from (John) Weber at Virginia Dwan. Weber had it over his desk, a soup can.

GM: What flavor?

DH: It was Tomato. And Irving's show was on. Irving was selling them for $100. And I got this one for $75, I thought I got a good deal. Then I got a Kienholz, it was a mannequin's head picking her nose, on roller skates. I paid $125 for that. So I had a $200 investment. My agent came in and said, 'You're married to a wealthy woman. You're squandering her money. Look at this. You're making a fool of yourself.' (laughs) 'Get rid of these things or I'm leaving.' So I said goodbye to him. (laughs) But nobody had ever seen any of this stuff before. To have a soup can, a comic book, in your livingroom. It wasn't happening anywhere else in the world.

GM: Did LA feel like a backwater then?

DH: Well, according to the Pompidou, we didn't have any art before 1955. (laughs) When I met Walter Hopps, and Kienholz, Berman, Herms, it was all so underground.

GM: Was there a sense of freedom in not getting attention? Or just being neglected? Or a little of both?

DH: Well, you always felt that Walter Hopps was going to guide you through this somehow. (laughs) I mean nobody was trying to sell. They didn't feel they had to sell, so they were doing printing, and other things to supplement their creative drive. Then finally the Ferus Gallery happened, and some of them had a place to show. And it became another thing, because Irving kicked it into a business. The other thing that really brought everything together was when Walter Hopps opened a Marcel Duchamp show in 1963 in Pasadena; it was Duchamp's first retrospective. Jasper came out (from New York), Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Rosenquist ... everyone merged. Walter was then director of the Pasadena Art Museum. He also did the first Pop Art show, before they coined the name Pop Art. ("New Painting of Common Objects," in 1962). He had Andy, Roy, Ed Ruscha ... the major guys.

GM: Did you know John Altoon?

DH: Oh yeah, very well. He was the one who taught us all to have studios, how to take storefronts, make them into studios. He and Bob Irwin and Ed Burrell had a place down under Benny Shapiro's Renaissance Club, it's where the House of Blues is now, they were down with no light in the basement, while Miles Davis and Lenny Bruce, these people were performing overhead. (laughs)

GM: You must have had some good times there, just kicking back and putting back beers, talking about art.

DH: It was incredible. I mean, the Ferus Gallery brought together a group of artists who were really tight. Irving Blum and Walter Hopps were just incredible.

GM: In a way, both the paintings and the photographs are about recording a time and place, and a mood.

DH: Right, yeah. I mean, honestly--I hate to use the word "artist," but--I think that's an artist's responsibility, to reflect his own time. So basically, it's a little late, but at the same time, I finally did it. (laughs)

This article was written for and published in art ltd. magazine ![]()