After an abortive and abruptly terminated postgraduate career in the New York art book publishing industry, I returned to Seattle, hat in hand to my parents' home and re-examined my prospects. With a degree in English literature from Oxford University, I was able to secure a university-level night-school teaching job that left my days free to re-discover Seattle after an 11-year absence. The experiences while away from Seattle had been transformative to say the least. At first, I was not glad to be back.

Fast forwarding to re-inventing myself as an art critic in Seattle, a city sorely in need of them in 1977, I simultaneously immersed myself in historical and archival research on the regional art of the area — my childhood heritage for four generations, after all — and applied the context to my freelance reviewing of the exploding art scene, one situated, at first, in the newly declared national historic landmark district, Pioneer Square. That shifted, literally before my eyes, north of the Pike Place Market to the dicey Belltown area, known primarily for its sailors' bars, gay baths and flophouses. Belltown was a neighborhood that arose in the 1920s and 1930s after an existing "topographical anomaly," Denny Hill, had been completely razed in a fit of commercial progressivism, and subsequently dumped in south Elliott Bay to create an industrial, manmade port called Harbor Island.

The more I wrote about and met older and younger artists in Seattle and especially in Belltown, the more I realized that thanks not only to them, but historically also to the artists who moved here from elsewhere, or expatriates who returned home over time were able to shape the character, look and diverse aesthetics of Seattle's art scene at the time, which I call the Belltown Blues, for its blue buildings, blue sculptures, blue skies, blue monochrome and striped paintings. Belltown meshed perfectly with my own desires for community, friendships and companionship as I pined for the intellectual challenges left behind with my friends in New York. And then, they, too, dispersed across America to various university art departments, art museums, galleries and, in one ominous case, Iran.

Without realizing it, I was recreating a Frank O'Hara-type of narrative in Seattle for myself, but of Frank O'Hara the poet who became an art critic (as I was doing), and the one torn between living at home in Massachusetts and weekending in New York or Cambridge. The people I met in Seattle — artists, poets, "independent curators" (what was that?) — all orbited around a nonprofit art and performance space two blocks away on Tenth Avenue called and/or —always underscored, never capitalized or italicized. It was natural that I would stumble in on weeknight openings there since around the corner was the Comet Tavern, the watering hole for Reed College graduates such as myself, assorted displaced Midwesterners and lost Ivy League types. This was Capitol Hill, not Belltown, closer to the venerable Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park.

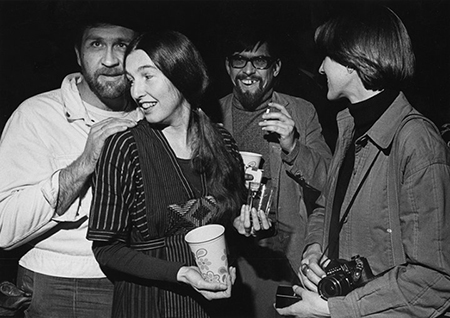

At and/or, thanks to low-profile director anne focke (her name, too, was always in lower-case), a dizzying succession of out-of-town artists, speakers, musicians, choreographers and installation artists nurtured and replenished an emerging contemporary scene desperately in need of younger input and older institutional programming. Martin Puryear built a yurt for his sister and called it a sculpture. Alan Lande built a campfire indoors, lit it, and called it performance art. The avant-garde composer Robert Ashley was followed by keyboard artists "Blue" Gene Tyranny and Charlemagne Palestine, whose rare appearances were never repeated in Seattle. Similarly, obscure members of the even more then obscure Fluxus movement regularly travelled to Seattle for "actions" and "interventions." By now even the Belgians knew about Seattle! The Seattle interludes of the visitors were fruitful for the locals and beneficial for the vagrant New Yorkers who returned home refreshed and surprised at the warmth of their reception.

When and/or "Notes" began publishing in 1979, along with other contributors I was able to complement my reviews for the three citywide newsweeklies I was writing for with a bimonthly forum that reached a more specialized art-world audience. For the first time, I knew exactly who would be reading my reviews and essays: the same artists whose studios I had been visiting and getting to know. This birth and death of a purported or imaginary readership — artists and the people who love them — became the first traumatic, innocence-shattering moment of my newfound career. After a few months, and a surprisingly negative response, I realized I could not count on such a sympathetic or responsive readership, even when hand-carrying a publication to them. I resolved to follow Gertrude Stein's comment in "The Making of Americans:" "I am writing for myself and strangers." What I hadn't realized was that, if the review or essay was not about them, very few artists in Belltown were reading other art magazines or about other artists in general.