"They're [the press] worse now than ever. They're loco. But that's OK. I put up with it. I use that word because of the fact that we made a trade deal with Mexico."

— Comedian-in-Chief Donald Trump,

October 1, 2018

Ken Kesey wrote "Sometimes a Great Notion" in 1964 (later a major motion picture). His Stamper family serves as a reminder, half a century later, that the Lead Belly song ("Goodnight Irene") from which the title is derived conveyed a truth that is today more timely than ever. "Sometimes I lives in the country/Sometimes I lives in town/Sometimes i take a great notion/To jump into the river an' drown." That about one third of the country wants to "jump into the river an' drown" in spite of a generally promising national reality underlines the spirit of what that free spirit Kesey was pissed off about back in the day. Why do we do some the of dumb shit stuff (as a culture now; we all know how good and smart we all are as individuals, right?) we do when, given the problems we need to keep chipping away at, we are in a historically enviable position. Today sure beats the Great Depression and World War II, and that's at the least. Yet millions do want to flush away the progress of a century, and by any means necessary.

The Stamper family of the novel unsurprisingly resists a strike called by union loggers (in those days the union movement was at its height) near the central Oregon coast. Daddy Henry has a motto, "Never Give a Inch," which signifies why this rugged logging family has built a successful business, and why Hank is beloved—but also scorned and isolated. Like any good tragedy, one edge of this sword implies its sharp opposite side. It cuts in both directions. The most memorable, or better put traumatizing, moment comes deep into the story when Henry, elder scion Hank, and younger brothers Joe Ben and Leland run into disaster preparing to run a haul of timber down the river without the help of striking employees. Henry is severely injured and taken to the hospital by Leland, while Joe Ben is stuck against a log, which rolls the wrong way enough to submerge his head just below the water's surface, with Hank providing mouth-to-mouth as they wait for hoped for assistance.

Kesey may have been one of the best American novelists of the last century, but he may be better known as the West Coast fomenter of the 1960s hippie "movement." He lead the Merry Pranksters and formed a collaboration with Timothy Leary and (then) Richard Alpert (later, Baba Ram Dass) to spike the punch with LSD at his Acid Test events, the house band for which was The Grateful Dead. It was all seen as a sacrament. But the sacrament of the Stampers has today become the animating principle of one of our two major political parties. Never give an inch. Never admit you are wrong.

A slew of psychedelic art, and art influenced by the psychedelics that flowed out of those heady days, divide Kesey from his creation. Not just musicians but visual artists constructed a new legacy that continues to reverberate: Bruce Connor, Jay DeFeo, William Wiley, Jess, R. Crumb, Alex Grey. The aesthetic range runs from deeply profound to profoundly silly. There are some extremely popular festivals, starting with Burning Man, that walk the same fine line that Kesey's Stamper family treads between powerful meaning and simple minded banality. Or maybe more to the point, between success and disaster. More prosaically, between getting the lumber to market and being under water just trying not to drown.

It is frequently discussed how ironic it is that, on the whole, in the thus far 20 months of the Trump administration, that source of national hilarity if you like late night TV and press conferences, has continued the steady economic improvements of the Obama administration. Whatever else we may think, neither the American nor the global economy has taken a nosedive. So give them credit, though it doesn't mean that the economy is being well managed. Trade wars, a tax "reform" act that steers over 80% of the cash into the off shore accounts of people who don't need it while adding $1.5 trillion to the national debt, or steps to trash both the Consumer Affairs Commission and the Affordable Care Act figure to do loads of economic damage a little further down the line. Especially to those ordinary folk that cheer the loudest at those fun rallies. You'd think that the coming mid-term election would be a far heavier lift for Democrats to take control of one or both houses of Congress than appears to be the case.

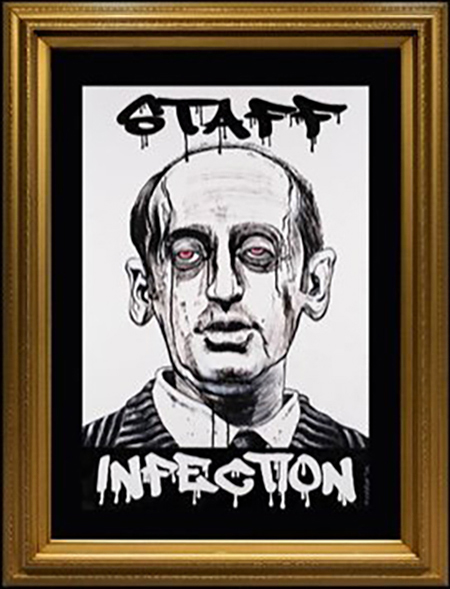

In a word, it's morality that is driving the political as well as the aesthetic train more than policy right now, as the battle over the Kavanaugh nomination the last few weeks has made clear for the umpteenth time. We can perhaps most clearly see it in art that captures the zeitgeist. Long time guerrilla poster artist Robbie Conal unveils his latest darkly humorous visual double entendres of currently infamous administration actors such as Steven Miller, Sarah Huckabee Sanders and so many others (in L.A. at Track 16), only the latest in his over thirty years of joyful and sharp eyed rebellion.

The exasperation is palpable. The latest iconic media image includes a parental admonition: "Don't look away from me," Ana Maria Archila tells Senator Jeff Flake in the Senate Office Building elevator. His party is caught between that open elevator doorway to admonition and a closed door of visible exclusion. They know it. The polls show a consistently widening gap in the run-up to the mid-terms, and it's because Archila so concisely reflects the feelings and thoughts of moral outrage shared by many, many millions, and not just women. In what is now buried in some now misty and mythological past, the party of personal responsibility has become the party of the Faustian bargain, gambling every shred of pubic integrity for twenty pieces of political silver. Having been made, their only viable option looks something like this: Never give an inch.

The current ruling party in America has constructed quite an edifice: Monopolize power by minority rule. But like Henry Stamper's it's a house placed on the banks of a river widening with natural erosion, and the occupants are frantic to build a protective wall and make the river a moat. Like the Stampers, they decided to go it with only their most core supporters, rabid for a feeling of safety, conveying to the rest of us to go fuck ourselves and stay the hell out. And now they are politically and culturally underwater, engaging in mouth to mouth, locked in a kiss with partners they do not know whether to love or despise in hopes that help is on the way.

Oh yeah, getting back to Hank and Joe Ben. Eventually it dawns on them how silly they look, sort of kissing like a couple of fags (hey, this is who they were in 1964). Silly becomes funny, and funny suddenly is not so funny.

Joe Ben laughs.