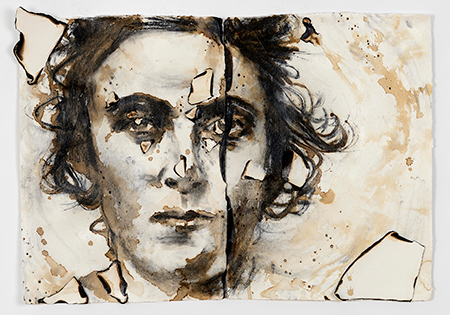

Last month, making the gallery rounds in San Francisco's Minnesota Street Project, I was reminded of the links between art-making, political divisiveness, and the brutal destructiveness of fire. The wildfires that consumed thousands of acres throughout California earlier this year seemed to creep into the Minnesota Street complex by way of artist Monica Lundy's "burn paintings" at Nancy Toomey Fine Art. Lundy, who is based in Los Angeles, harnessed the power of fire in her new body of work, entitled "Deviance: Women in the Asylum in the Fascist Regime." Using candles, cigarette lighters, and kitchen lighters, she singed and scorched her mixed-media paintings of women unjustly institutionalized during the regime of Benito Mussolini (Lundy co-conceived the project with historian Annacarla Valeriano while in residence at the American Academy in Rome). The timing of the exhibition, opening at the end of a historic wildfire season, was coincidental but symbolically pregnant. Fire, as Lundy has written, "is evocative of many things: futility, helplessness, rage, and impermanence. It also has a redemptive quality, carbonizing matter, information, and evidence, reducing and purifying everything to the same state of nothingness."

Taking in the show I was struck by the ways in which fire and the larger phenomenon of oxidation are apropos to our times. As life has gone on since Election Day 2016 and so many of us have become inured to "the new normal" of daily assaults to the pillars of our democracy, it has seemed that even as the underpinnings of civilized society are burning to the ground, many Americans are blithely "fiddling while Rome burns," returning to business as usual and anesthetizing ourselves with the usual distractions: Netflix, celebrity gossip, art openings, social media, and virtual-reality gizmos of sundry stripes. Who will extinguish our civic bonfire, a conflagration personified by a man whose signature phrase for years was "You're fired"?

Because of its universality — we are all oxidizing, after all, decaying down to our very cells — artists have used forms of fire and oxidation as a pictorial tactic for millennia. The patinas that give bronze sculptures their cornucopia of finishes are products of oxidation. The varnishes that painters have long slathered on panels and canvases have oxidized over the centuries, burying once-bright pigments under strata of sepia-toned grime. In the 20th Century, Andy Warhol wryly co-opted the Classical lineage of the patina in his "Oxidation Paintings," notoriously created by urine oxidizing copper-infused paints. In 1970, John Baldessari famously burned his painting output from 1953 through 1966, titling this clearing of the proverbial slate "Cremation Project." Likewise, Gerhard Richter used box cutters and fire to destroy about sixty of his photo-based paintings from the 1960s, among them images of Adolf Hitler and other Nazi-related propaganda. More recently, Dakota tribal elders originally planned to burn artist Sam Durant's controversial wooden installation, "Scaffold," after its ignominious run at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, but later decided to bury it instead, consigning it to a slower form of decay.

Here in the Northwest, at least two artists employ oxidizing processes to "cure" their work. Seattle-based painter Jaq Chartier conducts experiments, which she dubs "tests," by using different paints, stains, dyes, and other media to create sumptuous rows of mutable colors, which sometimes intensify over time and sometimes blanch. Portland-based artist and fashion designer Rio Wrenn creates intricate geometric patterns on silk by letting metals rust onto and into the fabric. In both cases, processes we typically think of as corrosive wind up birthing objects of astonishing beauty.

Similarly, in Lundy's "burn paintings," fetchingly lyrical portraits emerge not only from a destructive element, but also from subject matter that is anything but benign. From the 1920s through the 1940s, the subjects of these images were forcibly committed to the Sant'Antonio Abate, a psychiatric hospital in Teramo, Italy, for the dubious accusation of being "bad fascist women," a sham diagnosis with symptoms variously linked to hysteria, willfulness, and being deemed unsatisfactory wives or daughters by their husbands or families. That the stories of these victims of systemic injustice could emerge as hauntingly beautiful images, brought forth by a scholar's research, an artist's hand, and the transformative effects of flame, is a testament to the redemptive power not only of fire but of aesthetics itself. One can only hope (and also organize, mobilize, and vote) that we in the United States will eventually emerge from our own current trial by fire similarly transformed: scorched, scarred, but ultimately with our principles restored and our moral leadership redeemed.