Continuing through December 22, 2018

Made in 1927, the “Misery and War” (or “Misere et guerre”) suite of engraved etchings by French modern art giant Georges Rouault (1871-1958) was not printed in full until 1948. By then, after the bleak 1930s, World War II, and the Nazi occupation, the prints’ subject matter of human suffering and cruelty was more timely than ever. France was undergoing a postwar nervous breakdown not that different from the one Rouault suffered at the age of 27, after which he became a confirmed devout Roman Catholic. His religious faith became the motivating factor in all his subsequent art. Many consider Rouault the greatest religious artist of the 20th century.

The exhibition divides the suite in two parts in two rooms, with easy access to supporting works by the artist in the bins, including prints from the “Circus” and “Passion” series. It was legendary dealer Ambroise Vollard who convinced Rouault to turn his paintings into prints, and who underwrote the expenses. Fortunately, Rouault followed his dealer’s advice. Visitors may recognize certain iconic images, such as “We believe ourselves kings ...,“ and “Love one another ...,” depicting Christ surrounded by the Apostles.

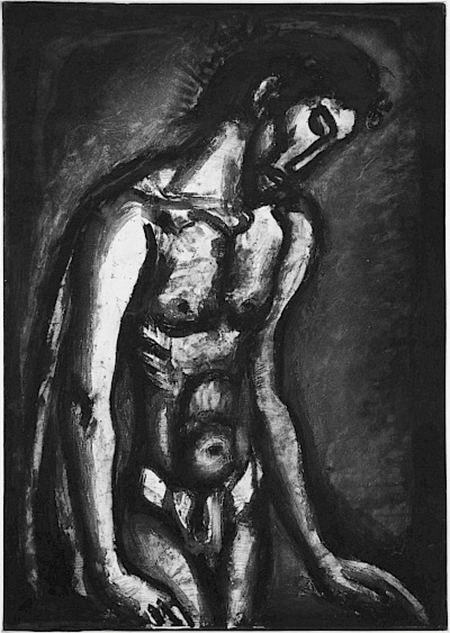

Seeing all 58 prints divided between “Misery” and “War,” we witness a museum-level exhibition complete with small catalogue and wall notes. Rouault trained as a stained-glass apprentice, was a renowned painter and eventually came to be regarded as one of the great printmakers as well. He broke all the rules of proper printmaking, dipping a brush in etching acid and working directly onto the copper plate. With additional unconventional methods like splashing, spitting and scribbling, he managed to achieve the goal of making his prints the equals of his paintings. In fact, several of the printed works follow directly from earlier paintings dating as far back as 1914, capturing the thick, emotional layering of his paint, here rendered in thin and viscous black inks.

Rouault’s religious feelings led first to his compassion for the poor and unfortunate, and then to his hatred of the French middle class that ignored them. Half the prints commemorate or honor the poor and miserable in peace and war; the others skewer the ruling elites who live far above and away from them. Sound like income inequality? Rouault actively called out injustice and institutional violence such as in the army and court systems. Anti-capitalist, anti-military, anti-clerical, anti-lawyer, anti-judge and anti-capital punishment, Rouault left no stone of oppression unturned. Yet, miraculously, he avoided any hint of contemporary literalism or propaganda. No religious doctrines are illustrated, though many titles come from the Bible. No political or military victor or vanquished is spelled out, but World War I is a heavy historical shadow on the entire suite, reminiscent of Stanley Kubrick’s black-and-white film about the fatal follies of the French military leadership in the First World War, “Paths of Glory“ (1957). Two of the prints, “The nobler the heart ...“ and “Face to Face,” depict aging officers chastising enlisted men.

Predominantly figurative throughout, the artist's male as well as female images appear downtrodden, yet erotic and dignified as well. Well-defined musculature gives the soldiers, prisoners or body of Christ a youthful demeanor all the more tragic considering their imminent slaughter or crucifixion, as in “Jesus will be in agony ...,” “Forever Scourged,” and “The prisoner is led away.”

It has only been in recent years that art historians have done a better job at situating Rouault. Once a “wild beast” or Fauve, placed alongside Matisse, he’s been largely removed from that category. Later called the only French Expressionist (along with Vlaminck) he’s also been stripped of that dubious title, although his affinities seem closer to Emil Nolde and Rembrandt than Dufy or Derain. Strangely, his stock was raised considerably by British art historian (and later exposed Soviet spymaster) Anthony Blunt who, quoted in the small catalogue, praises Rouault’s affinity for attacking the “corruption of the bourgeoisie. But Rouault’s motives were mystical not ideological, relating to Christ’s forgiving powers, not to the inevitability of a political apocalypse that would overturn society.

Students of Existentialism or admirers of postwar French theatre may recognize the three figures in “Omens” as the man with two women in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1944 play “No Exit,” with its tag-line “Hell is other people.” Ending on a note of hope, another central tenet of Rouault’s religion, a few prints point beyond despair, such as “It happens sometimes that the way is beautiful ...” and the magnificent “Tomorrow will be fair, said the castaway,” with its black stag leaping over the horizon.