It has been strangely reassuring of late to find several artists freely combining racial and cultural signifiers in the same figure. Against the backdrop of a pernicious tribalism in the political landscape emerges an artistic tendency I call "the melting pot aesthetic," after America's once great definition of itself as a place of mixed immigrant communities. Sanford Biggers' recent marble, figurative assemblages at Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago, and Jenny Saville's composite figures at Gagosian in Chelsea last spring stand out as possible guideposts for a newer deployment of cultural appropriation and identity politics.

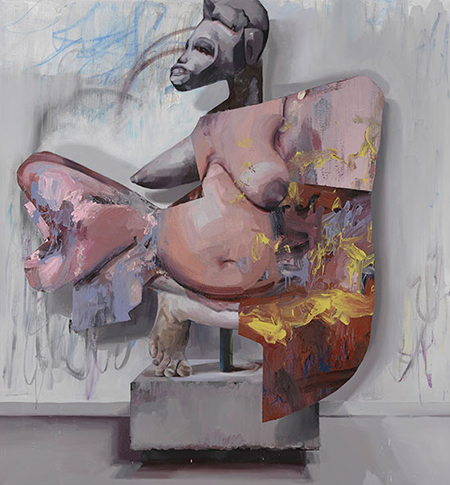

Biggers' pieces are classical figures topped with African masks and sculptures. The numinous creatures conceived through the alchemy of digital 3-D modeling and then rendered in marble by a Wisconsin stonecutter are beautifully uncanny. "Love Supreme" has the bust of a "Roman lady" donning a mask of the Dan people of Cote d'Ivoire. "St. Marvelous" hosts a Luba Hemba fertility goddess from the Democratic Republic of the Congo atop a toga-clad, classical figure from the waist down. Saville's massive "Fate I" juxtaposes a fleshy nude, torqued and painterly, with an African mask in grisaille as her head. "Fate II," another seated goddess (the titles suggest as much), has three fulsome limbs in rich pink tones that cascade over a chair, contrasting with the greys of her ambiguous black head — part mask, part realist portrait. Saville's disparate parts work together, the figures' intersectionality, its melding of blackness, whiteness and pinkness, is handled with such authoritative aplomb as to make the full image convincing.

Such composite creatures are hardly new, of course. Picasso's "Demoiselle d'Avignon" (1907) set a bar with his cultural potpourri of African mask, Iberian sculpture, Egyptian stylization, and archaic Greek statuary. But this canonical piece has been discussed primarily in terms of Picasso's part in shaping the "primitivism" of modern art, as well as the picture's spatial play in its pioneering proto-Cubist style. The idea of cultural appropriation as a possible means of reflecting the diversity of citizenship was not in play.

Hannah Höch also toyed with a figurative mélange of African and Western forms in her series, "From an Ethnographic Museum" (1930). Höch's photomontages of African and other nonwestern masks on women's bodies were shocking to behold because the images of women were a familiar element of the popular press from which she sourced her printed material. Höch's feminist collage strategy endures in the work of London-based, Wangechi Mutu or Chicago-based Marylou Zelazny. It is a technique that usurps the media's image of woman only to reveal its inherent biases and objectifications. This is a technique that certainly warrants further examination, but it does not share the same objective as the "melting pot aesthetic."

There are also the recent hybrid readymades of Danh Vo. His sculptural diptychs, stacking fragments of found artifacts from multiple places and times, jam cultural categories into erstwhile wholes. In "Your mother sucks cocks in Hell" a title coyly drawn from the film "The Exorcist," Vo places a partial, early gothic, wooden Madonna and Child on a slender plank above a fragment of a Roman marble statue of a child's legs. The effect is a captivating tension that mirrors the strangeness of early Surrealist juxtapositions. His "Dimmy, why do you do this to me," which is also a line from the film, puts another early Gothic Madonna and Child on top of a marble Roman satyr, just at mid-buttocks. Vo delights in upending sacrosanct icons to reshuffle the connotations.

In our time of fractious, political sectarianism, the combinatory impulse of Biggers and Saville, so distinct from Picasso, Höch or Danh Vo's, comes off as more pleasantly benign. Saville may be British, but the same troubles brew there, because of Brexit, in part, and inflamed by immigration fears. Saville's ladies are monumental, but far from being monstrous they are relaxed and assured. Biggers' elegant marble sculptures rest easily on the eyes, their strangeness nullified by the luxurious material and the seamlessness of the joining parts. Both artists accept the possibility of an easy alliance between different cultural types within the same body. If only our body politic might assimilate difference so well.