Continuing through May 12, 2019

Allen Ruppersberg’s retrospective feels a bit like a return-of-the-prodigal-son: even though his work has been exhibited periodically in Southern California over the last decade, it has far more consistently been shown in New York and Europe. It’s a comprehensive experience that unfolds through a myriad of installations and objects that embrace happenings, books, prints and the news, in addition to several seminal, first-generation conceptual art pieces that give way to more visually oriented explorations. One of Ruppersberg’s signature tropes, expansive walls of Colby posters (the once ubiquitous, Day-Glo-colored, text-based prints typically used for concert promotion), arrives near the end of the show. This iteration is paired with audio of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (headphones for listening to the iconic poem while viewing are on hand). Excerpts from the poem (sometimes phonetically spelled out), are mixed with event posters (“Every Thursday…Club Flirt…College Nights…Everyone FREE…$5 All Night w/College I.D.” reads one).

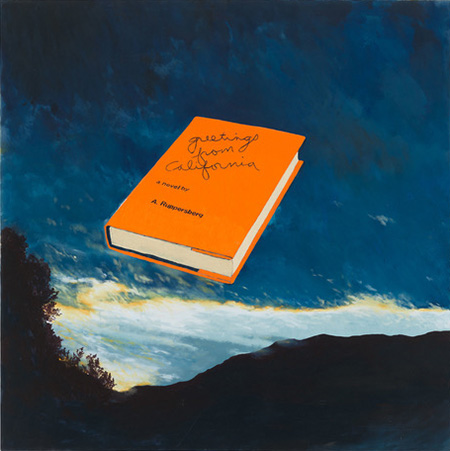

Books are Ruppersberg’s other go-to trope — or specialty, or default position. This manifests in everything from the exhibition’s mascot work, “Greetings from California,” a 1972 painting with the titular book, “by Allen Ruppersberg,” floating, Ed-Ruscha-like, over a landscape at dusk; to “The Picture of Dorian Grey,” Oscar Wilde’s book handwritten out completely in marker on 20 stretched canvases; to drawings of books, solo or in a cascading sequence; to the more satisfying physical books themselves. From 1991, a table is covered with 128 hard copies of Ruppersberg’s self-published, straight-to-remainder-status fictitious offerings, with titles including “A Different Kind of Never Never Land & Other Stories,” by the Nighthawk, and “Factum One Factum, Too, Factum One Factum, Too,” a Novel by Jon Doe Jr. The books’ fully hybrid nature epitomizes his career-long interest in blurring, or, better, attempting to render null, the distinction between art and life.

Because of their easy-going nature, it is tempting to underestimate the inventiveness and ambition of Ruppersberg’s early work. But he was already a fully formed conceptualist and producers of performances in his mid-20s, soon after graduating from Chouinard Art Institute. The wildly progressive thinking and art making that was going on around him was a critical stimulant. One must understand how much smaller that scene was at the time as well.

“Al’s Grand Hotel” (1971) took the form of a hotel and a happening — the Jesus Room and the Bridal Suite were among the seven rooms “rented,” and is archived here as a layered, four-wall projection, complete with a Terry Allen (a fellow Chouinard grad) soundtrack. Ruppersberg went on to have a very successful commercial career — his work is widely collected, especially for an L.A. artist emerging in the ‘70s who’s not Ed Ruscha or John Baldessari.

Ruppersberg has had a penchant for the obscure that sometimes embraces the macabre. A 1982 diptych, “Still Life,” which features virtually the same painting in duplicate, with paint-reproduced newspaper clippings telling the story of a young man who hires his friend to kill the friend’s mother, and the subsequent fallout from that murder, marks a striking break from his typically bland posture. It can certainly be regarded as a left-coast response to Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” paintings.

Ruppersberg later played extensively with the notions of “the collection,” and, by proxy, the collector. One framed silkscreen from 2000, hung among the Colby posters, titled, “Honey, I rearranged the collection to separate unhappy artists with problems from the rest. I couldn’t do it. It’s the whole collection,” is a good natured if edgy poke at artists’ self-absorption. At a concurrent show at Marc Selwyn Gallery, a 2018 print reads “Honey I rearranged the collection Because Formal Invention is what gets the attention Of critics, dealers and whores. But we as collectors Are not the inspectors Of positions taken for or against. We buy what we like When the mood strikes By artists we love and adore.” Take that, Mr. and Mrs. Collector. But skewering (or honoring) the artist-collector dynamic doesn’t dominate Ruppersberg’s oeuvre. Whether stereotype or satire, they shed light on the complex evolution of his work, the real subject being its increasing collectability, perhaps despite itself, over time. It’s a nuanced ambivalence.

As quintessentially dry and flavorless as some of the earlier conceptual work was, one early piece turns out to be as great as anything made since and serves as the last word. In “Untitled” (1971) a young and shirtless Ruppersberg, hands thrust in the back pockets of his jeans, chats casually with a friend, also shirtless, outside their apartment building. Below the black and white photo, the text of a mini-screenplay reads thusly:

Me: No, tell me.

You: You know the car wash on Santa Monica?

Me: Which one?

You: The one by the Orange Julius east of Doheny

On the north side.

Me: Oh, yeah. Sure.