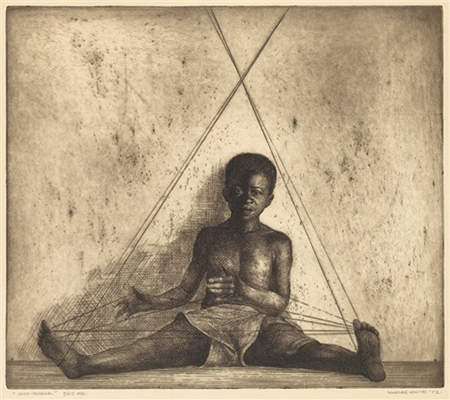

Eleven years older than Martin Luther King, Jr., the African American artist Charles White (1918-1979) was similarly a dreamer. Through his art, activism, and teaching, White envisioned an America where all people would be treated as equals. In his current retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, we see how White used his gift — he could draw like the Old Masters — to champion racial equality through sympathetic portraits and genre scenes that portray his subjects as strong, dignified, hard working and even blessed. The latter attribute, which is not really addressed in the exhibition's informative wall labels, is evident in the way White used light to suggest a spiritual presence. Most strikingly, divinity is referenced symbolically in "Cat's Cradle," a 1972 etching of a young black boy, seated on the ground against a wall. He spins a cat's cradle of yarn to form a triangle that circumscribes him. This image brings to mind associations with ideal perfection, as in Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man," as well as with the Christian Trinity. Not only a message about black pride, the image also suggests the notion that all of us are united by something higher than ourselves, whether this be interpreted as meaning that we are "all God's children" or, in a non-religious sense, that every human life is beautiful and precious.

Forty years after his death, White's vision of equality and belief in the dignity of all people is very much alive and artistically thriving, as evidenced in two satellite exhibitions. One features art by White's students, on view at the Charles White Elementary School, the former site of the Otis Art Institute. White taught there, and in fact was the first African American artist hired. The other, at the California African American Museum, sheds light on White's influence on younger black artists working today. "Plum Line: Charles White and the Contemporary," curated by Essence Harden and Leigh Raiford, is a sampler showcasing a number of known and not-so-well-known artists whose work reflects White's influence. Technical finesse and socially relevant content are ever present.

The exhibition at Charles White Elementary is particularly illuminating in that several of the participants reveal on wall labels what they learned from White and how they interacted with him. He was an approachable mentor, who introduced students to Michelangelo and Raphael as well as to jazz and blues. He encouraged them to know their roots and find themselves, and he taught them, most importantly, about the social responsibility of the artist.

While former White students such as David Hammons and Kerry James Marshall have enjoyed a national spotlight, one cannot help but want to see similar attention devoted to lesser known Otis alumni such as Dan Concholar, Alonzo Davis, Judithe Hernandez, Gary Lloyd, Greg Pitts, Kent Twitchell and Richard Wyatt. For now, one can drive around L.A. to visit some of the splendid murals by the latter two to gain a broader appreciation of White's legacy. His respect for artists is echoed in several murals by Twitchell depicting artists as noble figures. In one example, Twitchell transformed a freeway underpass into a contemporary altar, adorned with facing portraits of L.A. artists Lita Albuquerque and Jim Morphesis as seemingly holy figures, their hands raised in a triangle-shaped gesture (both have addressed spirituality in their art).

In Wyatt's mural at the Capitol Records building, black jazz legends such as Billie Holliday, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Nat King Cole are assembled together in a golden light. In another mural at Union Station, Wyatt commemorates the history of Los Angeles with similar elegance in representing the Native American settlers of the L.A. basin and contemporary Angelinos. (For more information and locations of these and other murals visit the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles website [www.muralconservancy.org).

The CAAM exhibition also reveals how White remains an important role model for contemporary black artists who offer poignant and ingratiating portrayals of everyday life in black communities, who are adventurous with materials and forms (paying homage to White's experimentation in printmaking), or who are politically engaged through their art practice. One painting from the last category is particularly stirring as commentary for the present moment. In Michelangelo Lovelace's "I am American," a mixed-race crowd stands united before a large backdrop of the American flag, staring directly out at the viewer. In the back row, an androgynous figure with dark pink skin, suggesting that the person may be biracial, holds up a sign that in plain American street language reads "Don't start no shit, Won't be no shit! America strong." Although painted in 2015, the painting speaks to the strength of the growing resistance to the hatred and racism that has defined the Trump era. Charles White would certainly be pleased with Lovelace's painting, and more that the work of so many artists he has influenced moves us one step closer to what he envisioned through his art.