Many artists over the past few decades were ahead of the curve in terms of subject matter dealing with social inequality, injustice and other issues of urgent topicality. Selma Waldman, a Seattle artist who died in 2008 at age 77, wrestled with her determination to draw attention to human rights abuses, beginning with the Holocaust and continuing right up to South African apartheid. Like so many artists, contrary to the van Gogh myth (values and reputations climb after death), Waldman's stature further plummeted because, later in life, she was unable to sustain fruitful relationships with galleries, curators or critics. Part of this was a result, in my opinion, of her undiagnosed bipolar condition or manic-depressive illness. The other part involved the unflinching, graphically violent appearance of most of her art: torture, interrogation, executions and other nearly unbearable scenes of political murder and assault on innocent individuals including parents and children. Waldman was a courageous artist, committed to paying attention to the underside of American and global political life.

Did Waldman sacrifice her career for her most heartfelt cause, the cruel treatment of innocent people? Or did her strong identification with the subjects of her art drive her off the deep end? Both cases could be made. Because she was an avowed Marxist, for openers, she was suspicious of art dealers even though she agreed to exhibitions. When she deigned, Waldman insisted on prices based on no reality other than her own confidence of their worth — and invariably nothing sold (e.g., $10,000 per drawing). Consequently, she was poverty-stricken most of her life.

The Selma Waldman Legacy Project was founded by her son, Rainer Adkins, in 2010. Unfortunately, little if anything to renew interest in her substantial achievement has happened. Except for a memorial survey at Seattle Central College shortly after her death, curated by Dr. Susan Platt and titled "The Pornography of Power: The Anti-War Art of Selma Waldman," there has still been nothing remotely resembling a fuller retrospective survey either at an art museum or gallery. One would think this would change with today's younger, socially conscious curators, but few are aware of her art — or are frightened off by its brutal, searing character. She is also a dissertation topic waiting for an ambitious young art historian. An American Käthe Kollwitz? Her marginality and peripheral status should be moved closer to the center in good postmodern fashion. What are they waiting for?

Waldman's background in Texas made for an unlikely revolutionary. Born in 1931, a child of the Great Depression, she followed her B.F.A. at University of Texas in 1952 with a Fulbright Fellowship to the Berlin University of the Arts between 1959 and 1961. These were two years that changed her life: her travels in Europe looking at important art; her meetings with international students in Berlin included those from South Africa whom she befriended; and her exposure to the work of Kollwitz, possibly the biggest influence on her subsequent art.

Before her move to Seattle in 1957, she was represented extensively in competitive art museum exhibitions in the Southwest, including her debut at the Fort Worth Art Center, the 1953 Dallas Museum of Fine Arts annual, and three versions of the western states annual at Denver Art Museum, where her work came to the attention of Edward Hopper biographer Lloyd Goodrich, art critic Aline B. Saarinen, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art director Dr. Grace McCann Morley.

Once in Seattle, she became part of an active leftist-activist community, participating in numerous public demonstrations and community meetings. Her first year, she was included in a group show at the city's first gallery run by a woman, Henriette Woessner. Interest on the part of curious curators and a dealer, Cliff Michel, who included her in various group exhibitions of figurative art, led to another European exhibition, "New Acquisitions for the Jewish Wing," at the Berlin Museum in 1982. The most important exhibition during her lifetime in which she was featured was "Absence/Presence: The Artistic Memory of the Holocaust and Genocide," organized by University of Minnesota Nash Gallery curator Stephen J. Feinstein, who followed up with "Witness and Legacy" at Seattle's Frye Art Museum in 2002. Waldman's lecture at the Frye was her last public appearance and her final art museum exhibition.

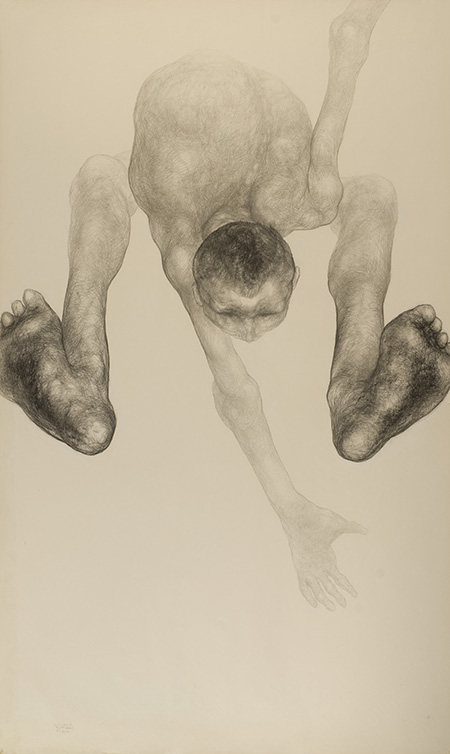

In Europe, the "Falling Man" series (1966-70) was hailed in the Jewish Section at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin in 1986. The grouping of ten drawings, based on photographs of corpses at Auschwitz and Dachau, isolated individual figures with contorted poses, setting them vertically on large pieces of paper to resemble falling figures. Beyond the Holocaust, Waldman's later works about the torture of apartheid victims brought full circle her "obsession," to use her son's term, with war, human suffering and unjust murder.