Continuing through August 31, 2019

Since the late 1960's, Anthony Hernandez has documented different aspects of the climate and culture of Los Angeles. Working in black and white as well as color, his subjects have been the full range of the city’s multifaceted sub-cultures, ranging from homeless encampments to Rodeo Drive. It is worth comparing the current series, “Screened Pictures,” to “Public Transit Areas,” Hernandez's series of black and white photographs from 1980. In “Screened Pictures,” Hernandez captures individuals who are unaware that they are being recorded. They appear in the distance, or as soft silhouettes, the mesh acting as a barrier between photographer and subject. Shot in broad daylight, the individuals seen in “Public Transit Areas” wait for buses in wide open spaces that call attention to the surrounding architecture and signage, as well as the streets receding into the distance. The earlier series is more about location and the passage of time than the individuals depicted.

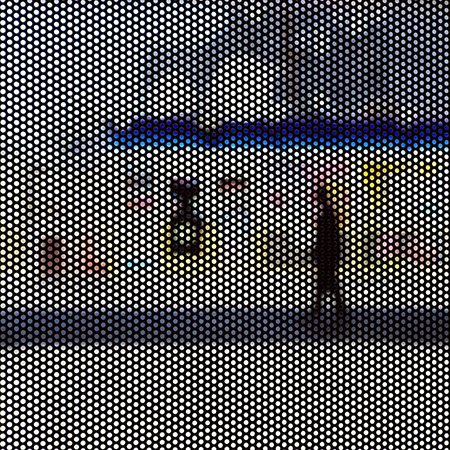

When I think about bus shelters, I imagine a roof, a few seats and places for advertisements. I do not recall their color or materiality. After viewing “Screened Pictures,” I tried to re-visualize these banal structures. Many, like those that appear in Hernandez's photographs, have walls of black metal mesh that serve as a visual and physical barrier between those waiting inside and what lies beyond. In these evocative works, Hernandez focuses his camera on the mesh, which becomes an opaque grid with circular perforated holes. Up close, the images are abstractions, but when seen from across the room, they coalesce into identifiable locations, discernible from these blurred fragments.

To create his images, Hernandez plays with depth of field, that is the distance between the nearest and farthest objects that are in acceptably sharp focus. Usually, the more light in a photograph, the greater the depth of field. The eye, like the camera lens, vacillates between these two zones of the image, trying to make sense of the abstraction and what caught Hernandez's eye in the distance. The “Screened Pictures” also reference Pointillism, given that these photographs require the mind's eye to complete the picture. If the perforated black foreground were removed, what would remain would be a perfect Pointillist image. Hernandez is interested in the interplay and tension between these two elements and the specifics of what is going on in the fuzzy background.

Most of the “Screened Pictures” are shot straight on, though a few display a skewed orientation where the perforated holes become slightly elongated due to the viewing angle. In “Screened Pictures #8” the pink awning and a trace of blue lettering cohere into an image of a "99 Cents Only" store. The exact location is unimportant; these stores are fixtures in the contemporary Los Angeles landscape and often, as in this image, there are people loitering in front of them.

A pitched tent by the roadside hovers into view in “Screened Pictures #43,” referencing rampant homelessness. A Mondrian-esque array of colored rectangles become Korean characters on a facade in “Screened Pictures #32,” illustrating the diverse cultures and communities of Los Angeles. When the enigmatic “Screened Pictures #19” coheres, it reveals a human silhouette passing by advertisements.

“Screened Pictures” depicts light and the vernacular architecture of Los Angeles. The inhabitants — people who wander the streets, take buses and are out in public — are present but more incidental. This is street life seen from street level. Though his subjects are veiled, they pointedly allude to issues of class and race that are endemic in Los Angeles. Hernandez reveals it by keeping his distance.