It’s been noted that the David Trulli’s mostly monochromatic ink, clay and varnish on masonite works are loose analogues for some sense of isolation we feel in lives lived through — literally — inanimate objects.

No doubt speaking to this theme is Trulli’s handsome compendium/visual shop box of sweeping corporate buildings, random piled up building parts, beams, vistas receding past multi-storied facades of sterile glass and non-descript references to steely structures that man hath wrought but does not apparently inhabit.

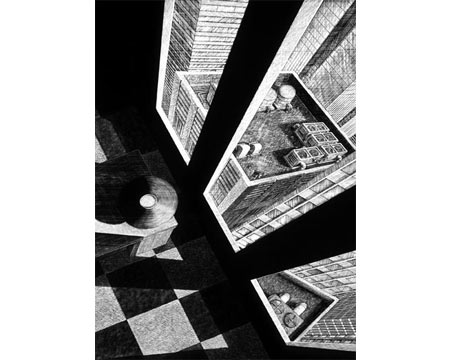

Indeed, in “Vanishing Point” a massive phallic beam projecting headlong into our viewing space forms one programmatic arm of a sweeping foreshortened perspective system straight out of Leon Battista Alberti or Paolo Uccello. Like those tropes back in the Renaissance, this careful draftsmanship here draws vision and emotion precipitously back, forcing us along the way to take in a whole “city” of empty urban fragments arranged tightly, obsessively in this deadening silence.

So the whole alienation vibe is there, for sure, along with as many other potential reads as there are viewers. But it seems frankly the least interesting thing to note for a few reasons. First because like our stressed adrenals shooting fight-flight cortisol into us every single day on the 405 Freeway for say 25 years, the body stops noticing the aberrant and simply adapts — the abnormal becomes the new normal. So I am not sure if we any longer feel or see ourselves as practically, urgently or even poetically isolated; on the contrary, we see ourselves as “networked in,” “hooked up,” ever potentially “Friend-ed.”

In Trulli’s undeniably dystopic “Swim Until You Can’t See Land” we are brought by large, abstract shapes to peer way, way down from the very top inside corner of a stiletto skyscraper. We’ve been placed by his clever hand in the position of some tiny creature hanging on for dear life to the corporate rafters. A world we’re scared of or cannot enter telescopes beneath us in a space as constricted as an elevator shaft. This may well be Trulli inviting us to consider if our current lot is a healthy adaptation or a dangerous defense mechanism; but he is smart enough to not close down the narrative so narrowly that if you happen to be among the fortunate adapters feeling comfortably “hooked in ‘n tightly twittered,” there is room for your speculation here.

It is overly simplistic to couch this work as some new Marshal McLuhan related take on techo-angst. Edvard Munch’s “Scream” (made ridiculous by trinkets — but still a profound painting to stand in front of) gave us a non-gendered ‘psyche’ accompanied on a bridge by spritely dressed city-slicker pals, but who feels unhinged and alone nonetheless. In the more than a century since, the chasm between “me-ness” and “you-ness” inherent in living and intimacy has been a strong subtext in art, from dada to Richard Serra’s “Big Arc.”

What’s positive here is that as much as Trulli’s images can seem to some like apt odes to human remove in the Age of Steve Jobs, they can just as easily come off as Bauhaus-ian, or Ann Rand celebrations of large, muscular progress-cum-techno-capitalism; have a look at ”Twist,” it is macho and assured if it is anything. Like Charles Sheeler’s slick machines or late 1940s noir fiction, Trulli can be at one glance so handsome, back lit and inviting as to verge on homage to strength, city and industry; then at another so wildly oppressive, claustrophobic and sinister (even at the 24 inch scale) that you wanna don your Birkenstock sandals and go camping immediately just to convince yourself there is something sprouting, messy, unpredictable and oozy out there where birds/bees/people and not just hard drives couple.

Published courtesy of ArtScene ©2010