Through September 27, 2019

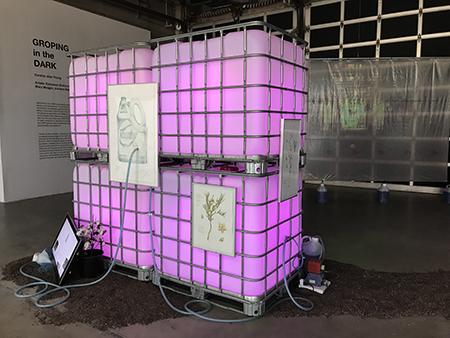

A sense of permeability pervades the gallery space where curator Alex Young has gathered eclectic meditations on the relationships between body, mind and earthly matter. Two large chemical tanks immediately beckon us into the space. Each glows with a neon pink color, surrounded by a metal casing with intersecting silver lines that convey order, containment and a clean modern aesthetic. There’s beauty here, but also danger. The work, “Terroir (formally Lubbock City Eternal)” by Caleb Lightfoot and J. Eric Simpson, serves as a visual preface to the story that unfolds. Further exploration of the space suggests the horrifying extent to which human bodies have been colonized by chemical culture.

Nearby is a video with the figure of a lone man, dressed from head to toe in protective gear, working inside a Bayer greenhouse. It’s projected onto a wide swath of greenhouse plastic, signaling that the contemporary obsession with digital culture has dulled human connections to the earth. It prompts reflection on the intersection of the organic with the artificial in everyday life. Botanical drawings mounted on the tanks nod to nature’s resilience. One of two artist books, titled “Enemy of the State,” explores the history of major chemical and seed producers, from Dow to Monsanto. Nearby, two rectangular works lay side by side on the floor, each with a single word illuminated by its own lamp. One reads “Cash,” the other reads “Crop.”

Other artists push us to consider hormonal complexities of biological organisms. Hormones have been used to define, control, or alter human behavior — in addition to promulgating binary perspectives on gender and identity. The revelation here isn’t the fact that chemicals are constantly assaulting the human body, but that it’s the poignant expression of humanity in a hierarchical world, where others control the ways those hormones are manufactured and delivered. Mary Maggic’s “Genital (*) Panic” is comprised of a sculpture of human anatomy, featuring both anus and genitalia, mounted on a pole near eye level. Beneath it, HD video projections of images ranging from pesticide containers to packets of birth control pills swirl around in a circle, jarring us to consider the intersection of body and commerce.

An installation resembling a test kitchen is another standout. Created by Epicurean Endocrinology collaborators Liz Flyntz and Byron Rich, “Hybrid Kitchen/Lab” includes containers for substances such as methyl alcohol and acetone. They’re set on a portable counter alongside beakers and syringes rather than cooking utensils. Three charts with tips for creating hormone-hacking meals hang on a wall behind the counter. They’re throwbacks to a time when home economics was a standard course in American high schools, and creating chemicals was a sign of social progress.

Elsewhere in the exhibit a group of six globes, minimally altered beyond concealing much of their original imagery, fall short. Titled “A Great Green Desert: The World in Some Parts,” they’re one of five works by Ryan Griffis and Sarah Ross. Included is an experimental documentary titled “A Great Green Desert,” an exploration of two terraforming projects. Although the exhibit incorporates several themes that are significant to contemporary discussion about the environment and its interface with diverse species, including migration and placemaking, it feels like an academic exercise, punctuated with a select number for works that translate the contemporary research into artworks that have real emotional resonance.