Continuing through September 13, 2010

Squeak Carnwath is a poet who scrawls text on her paintings with all the urgency and mischief of a Banksy gone legit. At the same time, she's as serious as a child coloring with her crayons: completely focused and full of purpose. It's perfectly obvious to her why she made the sky green; she can't help it if you don't quite get it. While the poet is driven to write her words, obsessively reworking them into a thing of heartbreaking beauty, the child transmits the alchemy of enchantment.

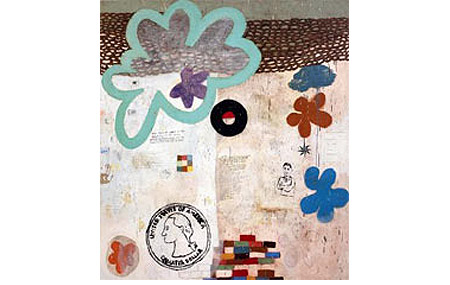

There is a great deal of joy in figurative paintings that carry vestiges of collage, graffiti, and even abstract expressionism. Loosely rendered flower shapes in drippy, solid hues suggest that everything's coming up roses in the artist's studio. However, closer inspection reveals layers of content as ephemeral, sweet, and clearly political as a trout in the hands of Richard Brautigan. Pieces of paper, their words scribbled child-like, become part of the picture. Carnwath's vocabulary is equally textual and visual. She uses line to section off planes within her canvases, and her sense of design is impeccable.

"Marked" is the very model of Carnwath's approach to painting: Beginning on the left side of the large, vertical piece is a row of short stripes - like a crudely knitted muffler - in cool tones of blues, purples, and greens with an occasional strip of muddy red. The rainbow-like column connotes the color palette of Wayne Thiebaud, a fellow figurative painter from the Bay Area. Across the rest of the picture is a background that appears to be some sort of faded and scratched wallpaper in cream with sage-colored flowers. Above eye level runs another row, this one a milky tan that could be a crocheted scarf for its texture and pattern. Occupying the lower right portion of the painting is a candelabrum aglow in its own light; somehow it seems part of the hominess of the work, as if the viewer's gotten a peek into someone's grandmother's parlor. Incongruously, a long series of words imposes itself like an insect on one's skin in an otherwise serene setting. In fact, the text tells the story of the female mosquito. She is the one who bites, seeking blood to feed her young. That blood, though, makes her too heavy to fly; it's not until she loses her water weight that she's freed to make her escape. A piece of ruled paper near the center of the picture presents these words, "To live is to be marked." Is this a warning? a Zen koan? To this viewer, it reads, as does the body of Carnwath's superb work, as a note about the temporal, and therefore precious, nature of creation.