Continuing through January 26, 2020

Tomas Ochoa’s work addresses themes of the environment, race, the southern border and especially colonialism. His large black and white panels, depicting rooms and jungles in Colombia, represent the larger geography of Latin America. There are also several images of tropical landscapes, which apparently are (or were when created) still untouched by human development. Also significant are his replications of 100-plus-year-old photos of the working classes. No matter the subject, they at first appear to be luminous photographs or perhaps photo-realistic drawings. This attracts the eye to examine them in detail. Ochoa’s deeper intentions are to reveal the region’s painful colonial history and its modern complex, often repressive social reality.

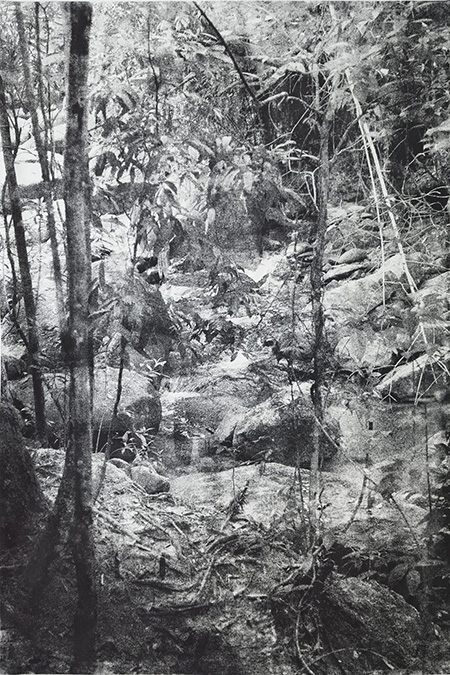

Ochoa appropriates some of his images, completing them with the use of a proprietary technique of substituting grains of gunpowder for photographic pixels. By then burning the gunpowder, the imprint of ash imparts an incandescent appearance, and even leaving a slight scent of burnt materials. Ochoa wrote in 2017, “They (the images) have been blown up to a large format by a procedure of substituting pixels for grains of gunpowder that fix themselves upon the surface as they burn.” Without first being informed of this method, it would be difficult to discern it.

The “explosive” technique’s deeper implication is to evoke the memory and continuing presence of colonial violence and racism in Latin America. Yet it is only Ochoa’s eight portraits of solemn indigenous people appropriated from century-old photos, “Free of All Inferior Races,” that overtly convey the sad and pervasive reality of exploitation. Ochoa writes that the titles of these portraits are direct quotes from the Colombian “School Manuals,” which teach students about their country’s history.

He further explains that their narrative is erroneous, characterizing the underclasses as barbarians and cannibals needing to be evangelized and trained to enter the modern world. This view was conventional wisdom throughout the colonial period and to come degree into the present day. Ochoa concludes, “The allegorist (presumably the artist himself) does not invent new images, he instead confiscates images to re-signify and to offer new meanings to them.”

One of the largest images is “Amazonia on Fire from the Paradise Black Line series” (2016), depicting a dense, un-besmirched Amazonian jungle from before the recent pervasive fires in the area. It looks back to a time when the area was populated mostly by gorillas, while presciently predicting — through the employment of gunpowder — the devastation about to occur. Another large-scale image, “Behind Glass” from the “Memento Mori” series (2019), is a magnificent illustration of a window-encased room with foliage and vegetation overrunning it. The room’s devastation suggests that time does not necessarily heal all wounds, and can even exacerbate them.

“Tropical Opera” (2019) is an even more dramatic image of a huge, overgrown bush, almost completely overtaking a once classy atrium. In “Fire in Athens” (2018), a large tree nearly obliterates a room. While we may initially see the elegance and harmony of both compositions, the deeper implications are of a world with radical inequality of wealth.

Ochoa’s political viewpoints are infused deeply into his finely wrought and often stunning painting. It evolves from personal life experiences that render his work emotionally compelling and intellectually informative.