The juxtaposition of ballpoint-pen-on-paper drawings of Il Lee and an exhibit exploring “The Thousand Faces of Vishnu: is highly evocative of how art — and the universe — work. One is a form of religious wisdom that forces us to contemplate the manner in which the Divine can never be contained. The other shows us the myriad ways in which a universal “energy” is captured and delivered to us over and over again in shifting panoramas. It, too, will resist solidity and will constantly spill into new shapes. Vishnu is ancient; Il Lee, is contemporary. But the underpinnings of both remind us that the world is, indeed, elegant and it continually morphs for our delectation.

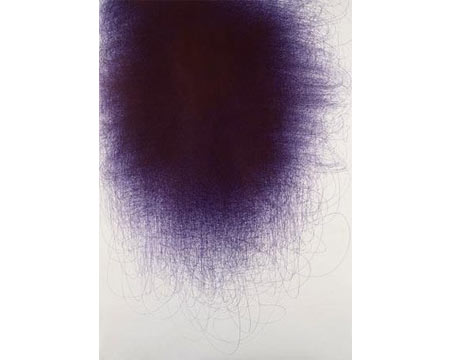

Since we can never fully divest ourselves of what has been referred to as “the perennial wisdom,” we might put it to good use if we bracket those insights delivered to from ancient Asia so as to focus on New York artist Lee. His work is anything but static. It is frenetic and highly charged with strident lines or loops that intimate a dynamic, changing world. Rather than “things” he shows us the “feeling of things,” His work is shot through with emotion and depth that resists naming. Like Vishnu, his work could easily have thousands of names because, as it stands, it’s sheer raw power. This is the stuff that makes planets move and hearts throb. It has a stealth that will bypass your mind and its frustrating “isms.” It’s sheer line, light and form that understands the wisdom of leaving form unfettered. It moves us closer to the ineffable.

In the corner of the gallery housing Lee’s work, you’ll see a huge canister of cheap pens, the kind kids purchase prior to school terms. They’re the empty repositories of the magic Lee deploys when he works on his large canvases. Some exceed five feet in height or width and, somehow, that’s quite fitting. These aren’t big ideas — however, they are big reminders of that remarkable cosmic stuff in which we all swim. We’re jarred into recalling that the pulsing heart of the made world, as Sanskrit texts remind us, is “not this and not that.” The divine, which I, for one, don’t mind closely aligning with the animating principal of art, will glide and slip past any attempt to lasso the real. Il Lee, however, manages to participate in that marvelous paradoxical dance of giving it to us by maintaining a kind of chiaroscuro of the real. It’s a show of light and shadow. And the enigma is what animates it so pleasantly. It’s the lure of the bright gods and their manner of circulating in our daily lives. It’s the whir, the sizzle and the whomped up glory that makes getting up in the morning, well, worth it.