When Gen Z-ers routinely dismiss the entire art historical canon as the work of dead white men, I’m two parts chilled and one part thrilled. What determined, righteous callousness! But recently, when several extremely smart young people I know threw Andy Warhol under that same bus, on the occasion of his retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, I felt a little disoriented. To those who witnessed his antics in real time, Warhol represented a pivot to a new, iconoclastic vision of what art could be, or be about. To an upcoming generation though, he’s just one more roadblock, the embodiment of a superficial, sexist, corrupt system that’s all about money and power.

The white man part is clear — meet the new boss, same as the old boss. But, dead? Are we really going to hold that against an artist? Since when did “dead” come to mean “irrelevant”? What about ars longa vita brevis? Isn’t one of art’s superpowers its ability to circumvent death? What about that hokey old saw about understanding the past through the eyes of those who came before us? And what about beauty?

In an effort to consider these ideas, and specifically to consider whether it makes sense to even try to balance the crimes of the dead against their accomplishments while regarding objects they made or accumulated, I took myself to the Field Museum of Natural History, a Gilded Age temple dedicated to deadness, beauty and the deep past.

The museum, which opened in 1894, was named for Marshall Field, famed Chicago luxury department store magnate and the rich white guy who came up with the endowment. Later Field bankrolled hunting expeditions to Africa to bring back specimens. For this job, the museum dispatched naturalist and genius taxidermist Carl Akeley who sometimes brought along his wife, Delia, also a naturalist and hunter. (In those days that combo was not considered an oxymoron.) Many of those specimens, artfully stuffed, are still on display, and the couple’s most famous kill, a pair of ten-foot tall fighting African elephants, graces the museum’s entry hall. Delia took down the larger of the two animals, which was said to be carrying 180 pounds of ivory in his tusks.

But dead animals cut down in their prime and taxidermied to the level of fine art, heartrendingly gorgeous as they are, are just appetizers here. The main course in death is a trip to the basement. Here dwell the Egyptian mummies, well preserved remains of actual dead humans that have presumably been stolen, along with cats, falcons and one small crocodile, from their tombs. Lovingly preserved and prepared for an afterlife they would never achieve, they now live out eternity in a basement in Chicago.

The origin of these human remains is unclear as are the circumstances and agreements that led to their arrival here. All the museum tells us is that they were purchased from an antiquities dealer in 1894 by Edward Ayer, the Chicago businessman who was the museum’s first president. Today, museums have policies against acquiring objects without known provenance, and international laws prohibit the theft of cultural artifacts. Not so in 1894.

Even more concerning than the probability that the mummies on display were looted, then sold to an American collector, is the fact that human remains are on display at all. Would any of us want our bodies or those of our loved ones dug up and put in a glass case in a darkened room for children to gawk at thousands of years hence? To the museum’s credit, wall text reminds visitors to be respectful, and the names of the dead, when known, are posted alongside a prayer that honors them. Nice touch, though full respect would require these remains to be returned to their graves, an act that doesn’t even seem possible now.

The viewer is left wondering if this state of affairs is softened by the fact that these objects are educational and thought provoking and kind of enchanting, offering a glimpse into the past that sheds light not only on past civilizations but also on our own dark history.

Some of the most important dead things on display in the Field Museum may not be objects at all, but ideas.

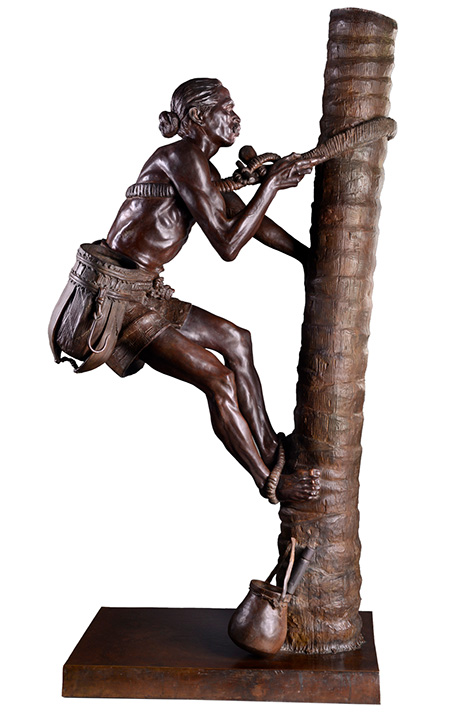

Wandering the second floor, looking for the gemstone room to ease my growing queasiness in the face of all this plunder, I happened upon the newly (2016) if only partially reinstalled “Races of Mankind” exhibit. Unveiled in 1933, this exhibition of 104 figurative bronze sculptures was commissioned to depict the “world’s races in a dignified manner.” It was also intended to instruct viewers in how physical differences argued for a racial hierarchy. This sounds awful but here’s the catch: the sculptor, Malvina Hoffman, who had studied with Rodin, was perhaps too gifted to fulfill the commission as intended. After a yearlong trip around the world, along with her photographer husband, to research and document facial and bodily types and find suitable portrait subjects, then another three years executing the sculptures, Hoffman concluded that her subjects were not types at all, but individuals. What she’d found were simply human beings, many quite beautiful, who, when rendered in bronze turned out to be, except for gender, remarkably similar looking.

The show opened to great fanfare in 1933 but unsurprisingly fell out of favor in the 1960s. In 1969 the exhibit was dismantled and the sculptures put in storage. But something about them nagged at the curators. Now, a selection of about half of the original 104 pieces are back on view, along with wall text and videos that tell their story, addressing how recently wrongheaded ideas about race persisted.

This context is good. History is good. But the didactic element here is unnecessary; the work speaks for itself. The intention of the commission was completely subverted by the eye and talent of the artist, whether intentionally or not. Instead of pseudo anthropology about racial types, the show now serves as another humbling reminder of our ill informed past, thus proving the usefulness of holding on to dead things. Not only white men but every living thing must die. Art, though, lives on and so do ideas. Since not all ideas are good, we had better pay attention.

So I’m glad this stuff wasn’t destroyed or relegated to permanent storage, partly for its power to educate and mostly just for its beauty, which after all is the best kind of education.

A friend asked me recently if I’d seen the Warhol show. How was it?, he wanted to know. I tried to explain about Gen Z-ers and dead white men and the Field Museum. Mummies, elephants and wokeness. He looked vexed. Then he said, yeah but how was the art?