How did your love affair with visual art begin? I wish I could sit down with each of you and hear your reminiscences. No doubt your particulars would also contain universals that the rest of us could relate to, for the arts are where we discover most fully our common human capacities for empathy, catharsis, and the search for the sublime. A looming new year always drives us to reflect, and so as 2020 fast approaches, I find myself not only wondering about other people’s artistic origin stories, but also reconsidering my own. Here is mine, in a nutshell.

As a kid in rural Florida I used to look at art and architecture photographs in my grandparents’ Encyclopedia Britannica. My upbringing was not privileged, but in those pages my imagination could wander to times and places far removed from my reality. Could I travel to those places someday, I mused, and see those fantastical pictures and objects? As a pre-teen in the early 1980s, I went with my mother to visit the traveling Armand Hammer collection when it stopped in Lexington, Kentucky. I had heard of Leonardo da Vinci and Rembrandt, but to behold their drawings in person seemed surreal, and while I was not particularly taken with any individual pieces, the fact of their physical presence sharing mine exerted an uncanny power that I could not shake.

Not long afterwards on a family trip, I was toted along to Haussner’s Restaurant in Baltimore, Maryland (defunct since 1999), renowned for its salon-style installation of important 19th Century paintings once owned by J.P. Morgan and Cornelius Vanderbilt. I stared up wide-eyed and intimidated at those landscapes and portraits in gilded frames, knowing nothing of fine art except that it evoked a different ethos than what I was gleaning at the time from superhero movies and TV sitcoms. The following year I visited my Uncle Jim, who had worked for several years as a business executive in Japan. He walked my impressionable self through their collection of Asian art, including an ornate folding screen he was given by the Japanese government. With a hushed fervor he explained the piece’s intricacies of craftsmanship and symbolism, as if imparting secret knowledge. He was the first connoisseur I’d ever met.

In 1983 our family moved to Europe when my stepfather, who worked for the Department of Defense, was transferred to what was then West Germany. For the next five years, as we traveled on every available weekend and holiday, a passion took root within me for painting and sculpture, opera and the symphony, the grandeur of castles, cathedrals, and monumental public spaces. Young people need things to grasp onto as they build their characters; I was fortunate to be in a place with good stuff to grasp. Baroque and rococo art and architecture became my single-minded obsessions after I stood slack-jawed in the Amalienburg in Munich, the Wieskirche in the Bavarian countryside, and the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. I studied the Baroque day and night at the exclusion of all other periods of art. If it didn’t have gilded cherubs and curlicues, I wasn’t interested. Teenagers can be extreme.

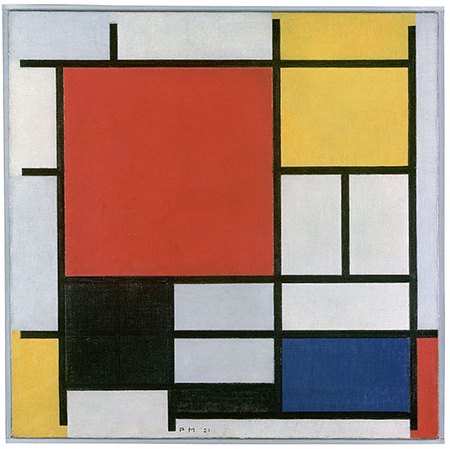

Back in the States, minoring in humanities at college, I opened a book in the campus library, saw a color print of a Piet Mondrian painting from 1921, and felt myself quaking inside. This was more than just an affinity. I felt an identification with that painting, which I saw as a blueprint for my own developing humanist worldview: the primary colors as concepts reduced to essentials, the rectilinear structure as the order endemic to the rational mind. That an artwork could seemingly concretize an entire epistemology was a revelation. Mondrian became my new hero, and soon I was devouring everything related to him and his De Stijl compatriots. It’s astonishing that one can feel bonded to an artist who died decades or even centuries before one’s birth. This is part of art’s magic. It is a kind of necromancy.

Between that epiphany and my life today as a critic, my erstwhile fascination with neoplasticism broadened into a devotion to Abstract Expressionism, minimalism and finally contemporary art. In 2003, attending the second iteration of Art Basel Miami Beach, I saw in person for the first time the work of Beatriz Milhazes, Gabriel Orozco, Liza Lou, Peter Halley, Kehinde Wiley and Ryan McGinness. Once again, I felt the world widen between my ears. I still get those same butterflies whenever I encounter an artist whose style and ideas resonate within me like a freshly struck tuning fork.

Looking back on my trajectory, I see how my growth as an art appreciator arose from a mixture of chance occurrences (dining in a certain restaurant, visiting a certain uncle, opening a certain book) together with knowledge acquired as a student and from books and documentaries. To me, this is not just an observation, it’s a call to action. If you can take a young person to a museum or gallery, or patiently explain why a beloved artwork or design piece in your home means something to you, it’s possible you might influence the course of their life. Much of the apathy increasingly present in our collector communities, not to mention declining attendance in museums and also at the theater, symphony, opera and ballet, can be traced to the withering of arts education. Enthusiasm for all things aesthetic does not sprout from barren soil; it must be inculcated and nurtured. Here is my wish for 2020: that we resolve to do everything in our power to pass our passions along to new generations in ways small and large. It isn’t hyperbole to suggest that the soul of our country and world — or at least a great big shining chunk of it — depends on it.