One of the conversations that earned high visibility in the recent Democratic Presidential debates was about how to get big money out of politics. With Bernie Sanders continuing to make the case that something is amiss when the one-percent control most of what happens in our government, Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg getting into a confrontational exchange over the acceptability of certain donor dollars, and Amy Klobuchar calling for an end to Citizens United, it is an issue deserving of our attention. Yet, if one has been following the art world for the past several years, it is valid to ask why it has taken so long to get this discussion out in the open. After all, artists have been crying out about money corrupting politics since the dawning of the Reagan era. And, because they are artists, many have been particularly creative in their messaging by using genuine currency as an artistic medium.

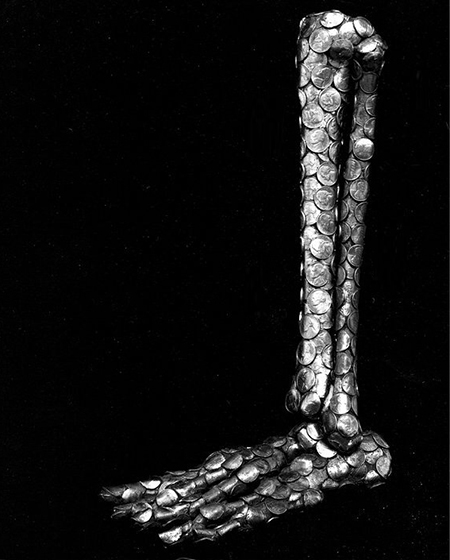

In 1982, Gary Lloyd used everyday coins like mosaic tiles to create a series of sculptures critiquing the exorbitant and unnecessary cost of war. For an exhibition at Ulrike Kantor Gallery in Los Angeles, Lloyd expressed his objection to the Reagan administration’s billion dollar defense spending by covering plastic medical skeleton parts with everyday coinage. A particularly eloquent work from that exhibition was “A Lien Leg,” a lower leg and foot coated with nickels and dimes. In pairing currency with severed limbs, Lloyd called attention to the plight of Veterans with disabilities, and the corresponding high cost of health care. Considering the degree to which the situation has worsened almost forty years later, Lloyd’s coin-clad objects were prescient.

Marshall Weber was on a similar wavelength in 1986 when he exhibited a swastika sculpture made of dollar bills at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery. When the work stirred up controversy, Weber explained that he was simply observing an historical parallel between the American and Nazi Germany’s commerce systems, in that political acts in both countries were motivated by economic concerns. Viewing the dollar bill as the “real American symbol,” Weber went on to create several small-scale sculptures and collages from U.S. dollars. In a miniature chair wrapped in bills, titled “Seat ‘O Power,” he suggests that money rules everything. In one of his collages, a dollar bill superimposed over a map of the Colonial U.S. and accompanying text quoted from Malcolm X remind us that George Washington, whose face graces the ubiquitous $1 bill, was a slave owner who used human beings as commodities.

The corrupting effects of the almighty dollar also motivated San Antonio’s Ken Little in the late 1980s to make his first “$1 Bill Suit.” Constructed by sewing dollar bills together, this and subsequent dollar business suits were installed draped over suspended armatures, implying the presence inside them of what the artist conceived to be invisible bodies with no souls.

Today, increasing numbers of contemporary artists are making art from currency, with paper being far more popular than coin (which makes sense because paper is more flexible). Calling themselves “currency collage” artists, Mark Wagner of Brooklyn and CK Wilde of Los Angeles have been cutting up money and using it to construct intricately detailed collages since the late 1990s. Wagner, who works exclusively with U.S. currency, is best known for his 17 ft. by 6 ft. 3 in. collage “Liberty,” which he fabricated from 81,895 cut fragments of 1,121 dollar bills. A satirical narrative showing the Statue of Liberty accompanied by multiple vignettes, this mammoth collage is part of an ongoing oeuvre aimed at exploring connections between wealth, power, value and American identity. Wilde, on the other hand, employs a broader palette, using both foreign and domestic currency to address national and global issues. In a recent group show curated by Rosamund Felsen for West Los Angeles College Art Gallery, he exhibited a radiant, polychromatic representation of Ho Chi Minh shown as a scholar in a cave. Offering an alternative to the usual American viewpoint, Wilde celebrates Ho as a hero who helped free the Vietnamese from Imperialist domination. Based on an iconic photograph, the portrait contains a mixture of pre- and post-colonial period currencies from Southeast Asia, France, the U.S. and other areas associated with Vietnam.

In 2017-18, Wagner and Wilde exhibited currency collages in a group show at Houston’s LCD Gallery, as did Robin Clark of San Francisco, Jason Hughes and Oriane Stender of Brooklyn, and Justine Smith of London. Not all of the exhibiting artists, however, showed collages. Like Wilde, New Orleans’ Dan Tague works with both U.S. and foreign currency but, rather than destroy it, he recycles it. During the PTSD phase following Hurricane Katrina (which left him stranded on a rooftop and cost him his studio), Tague was getting fidgety. So he started folding dollar bills and discovered that different arrangements yielded words and phrases. The epiphany inspired him to photograph the folded bills and create political text-based work in the Barbara Kruger tradition. For more than a decade since, Tague has been exhibiting large photographic prints of money that he bent, folded, and shaped to reveal hidden messages, phrases that derive mostly from the political sphere, pop music, or everyday jargon. Initially he worked only with American dollars, but gravitated to colorful foreign currencies following an exhibition in Paraguay. Tague’s texts are consistently clever, witty or profound. With messages like “We need a revolution,” “Cash rules everything around me,” and “Opiate of the masses,” Tague informs us about the still-true, present-day effects of money.