While Susan Sontag was born in New York in 1933, Susan Lee Rosenblatt’s childhood and adolescent years spent in Sherman Oaks, CA were important for her later development. She learned about image and publicity from her grandmother’s earlier work as an extra in the film industry; she benefited from her advanced public education at North Hollywood High and at University of California, Berkeley. She formed her early literary education by haunting the used bookshops of Los Angeles, where she stole a copy of Thomas Mann’s new novel, “Doctor Faustus” and arranged to visit the writer, then living in Pacific Palisades, when she was a 16-year-old freshman at the University of Chicago.

For our purposes, it is worth examining her relationship to the visual arts. As a precocious genius who held academic teaching positions at Sarah Lawrence, City College and Columbia University, she also attended Harvard University, University of Connecticut, Columbia University, University of Oxford and the Sorbonne. Yet Sontag chose to withdraw from a promising academic future to pursue writing on culture. By so doing, she provided a role model for other critics who eschewed the narrow parameters of academia. Further, she expanded the purview of what culture could contain, namely popular culture as well as high culture; politics as well as philosophy; and, most importantly, film. When we pore over her collected writings or read the three best biographies (Carl Rollyson and Lisa Paddock, 2000; Daniel Schreiber, 2014; and Benjamin Moser, 2019), almost every other art form supersedes painting or sculpture. Preferring architecture, film, theatre, fiction, photography, dance and opera, Sontag gave contemporary art short shrift by comparison. After her death in 2004, Sontag’s friends scorned her interest in art, with André Malraux’s daughter, Florence, claiming “she had no eye,” and art critic Ted Mooney lamenting “she was virtually unable to see painting … [With Mondrian], she didn’t see the point of it.”

However, after her 1956 move to New York, when she came into contact with visual artists who attracted her attention professionally and personally and who influenced the direction of her interests without successfully recruiting her as an advocate, Sontag’s connection to the visual arts was transformed. For example, the seminal essay “Against Interpretation” (1964) may have been a pre-emptive strike against later, heavily interpretive magazines like Artforum, calling for an examination of art on its own terms, not as oppressive analysis. “Notes on Camp” (1964), even more influential, included references to Tiffany lamps and science-fiction, but no painters. Once ensconced in Manhattan, she came into contact with, first, Pop artists such as Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns (with whom she had an affair) and Andy Warhol. The latter filmed seven “Screen Tests” of Sontag. In “The Aesthetics of Silence” (1969), painters were mentioned to underscore the aesthetics of silence in composers John Cage and Milton Babbitt. Mark Rothko anticipates the all-black or all-white paintings of Robert Rauschenberg and Frank Stella. These provided Sontag with examples of un-interpreting art since there appears to be nothing to interpret.

With the 1977 publication of “On Photography” (perhaps her most significant work), Sontag bent over backwards to make the case against photography as art, insisting it is a mechanism of distancing from reality and hence unreliable and untruthful. This idea caught on subsequently and formed part of the Zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s. Not surprisingly, photographers who were at that time becoming recognized as fine artists, like Irving Penn and Peter Hujar, objected strenuously. Nevertheless, the book became “a bible,” as one reviewer put it. Today photography is fully incorporated into contemporary art, and its segregation as a separate art form is no longer a serious position. Thus, Sontag may have been more prescient than seen at the time. With the full-on interpolation of photography into the art world, the artists Sontag developed an interest in included Matthew Barney (also a filmmaker), Jeff Wall and Doug Aitken (both of whom used staged photographs and video as tools).

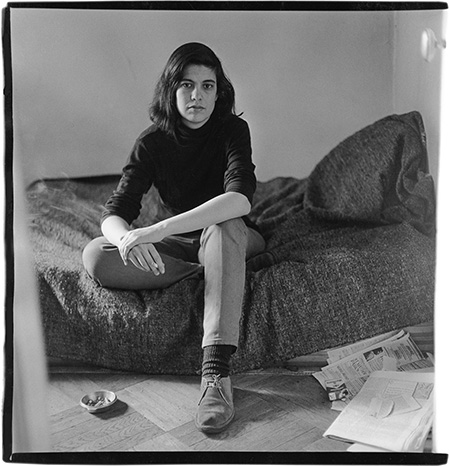

Drawing on her mother’s and grandmother’s experiences as movie extras, Sontag played the celebrity game assiduously, using photographers to cement what became her iconic status. Photography was a means to an end, not a form of self-expression, the very notion of which she despised.

Excessive publicity turned Sontag into a diva, which soon enough attracted the one American artist already obsessed with divas, Joseph Cornell. It is unclear how often they met (one biographer says only once, another posits a two-year period of friendship) but his numerous fan letters to her and his insane fantasies about her being the descendant of a French diva with the same surname, led to his own portrait, “The Ellipsian” (1963). Sontag may not have had an “eye for art,” but artists had an eye for her.