Continuing through April 12, 2020

Its pithy title notwithstanding, “She Bends” is a hip, crowd-pleasing exhibition spotlighting the international She Bends network of female-identifying artists who work primarily with neon. But the show has higher aspirations than being Instagram-worthy. First, “She Bends” brings attention to and supports women finding artistic expression through neon bending, a highly precise, hands-on, physically demanding craft. Second, the show illuminates the many ways neon finds a home in representational and abstract art, not just in neon phrases on the wall, but also in mixed media works and installations, mining the possibilities of such additions as pulsing lights and ambient sounds.

Some of the pieces offer more intellectual heft than others. If there’s a weakness to the show, it’s that the brightly colored word art (throwbacks to Bruce Nauman, Conceptualism and Pop Art) steals attention from more challenging works in which neon is just one of the materials. We are drawn magnetically to the glow of the messages — social, cultural and otherwise. Still, the darkened gallery makes for a perfect viewing environment, offering about two dozen artists and enough variety to appeal to anyone operating under the misconception that neon’s only use is in commercial signage.

Several of the text-based works provide an element of levity, as in Olivia Steele’s “Set My Soul on Fire,” where those words glow on the side of an actual gas can. Megan Stelljes’ wall piece “I Don’t Carrot All,” with its hard-to-bend cursive lettering, substitutes a plastic carrot for the punning word. Her other piece, “Party Banana,” strategically places two neon circles representing oranges near the stem of a neon banana, worth a chuckle for the sexual innuendo.

Feminist undertones in the works are plentiful, for instance, in the pink neon tubing of Eve DeHaan’s “Do You Know How Many Things I’ve Done Today?” It’s a succinct lament on women’s many roles. Meanwhile, in two non-text but efficiently designed works, Teresa Escobar explores neon’s ability to evoke sensuality; she bends the tubes to suggest breasts and nipples. Works with this kind of panache succeed because they dare to appropriate the historic, often gaudy, use of neon drawings and lettering in outdoor advertising. They cleverly subvert that purpose. Instead of being come-ons to gentlemen’s clubs, casinos, and the like, the works’ neon flashiness acts as a beacon of female empowerment.

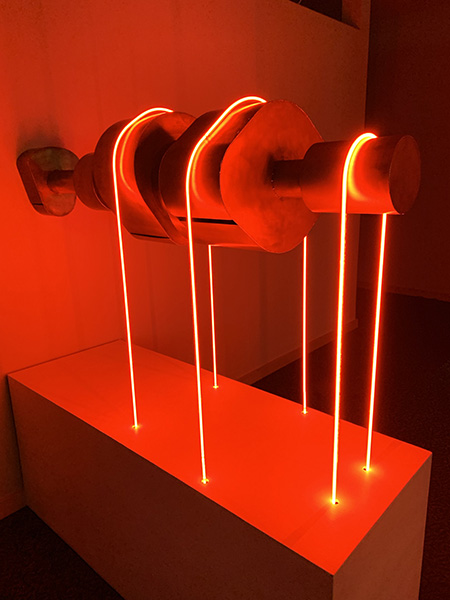

Turning to the exhibition’s handful of installations, the neon tubes of Carissa Grace’s “Comforter” are precisely interlaced into a bluish-white facsimile of a chain-link fence that drapes from the wall onto the floor. The artist states that this work deals with representations of home, though the sense of home here is not always as comforting as promised. Lily Reeves incorporates neon into her multimedia work “Ice Architect,” in which neon circles form a Venn diagram. A film projector fills the circles with the mesmerizing movements of shadowy forms — nondescript organisms, bodies, clouds and landscapes — accompanied by white noise. It conjures ideas about metaphysics and humans’ relationship to nature. Camille MacRae makes a case for neon’s incorporation into sculpture with “They Call Me Cam Jam,” in which white neon “strings” appear to hold a suspended camshaft in place. A number of other pieces wrap neon around and inside found objects in unexpected ways.

The artists of the She Bends collective often cite how they’re “pushing the boundaries of our medium beyond the confines of commercial signage.” The statement bodes well for neon as a more versatile medium, ripe for aesthetic experimentation, not just novelty.