Was scheduled to run through May 10, 2020

This exhibition of over 50 immigrant and first generation Chicago-based artists was first mounted in 2018 as “Living Architecture” at the nonprofit alternative space, 6018North. Located in a hundred-year-old house on the city’s northside, the notion of “home” in the curatorial premise was as much historical as it was domestic. The notion of “home” is further expanded in the context of its new version of the show at downtown’s Cultural Center. Inside this city-operated landmark building, “In Flux” underscores the importance of immigrant artists to Chicago’s art community, and indeed immigrants past and present to the city at large. As “In Flux” began as a project hinged upon architecture, so many of the most potent works in the show are installation-based, engaging the environment as integral to their content.

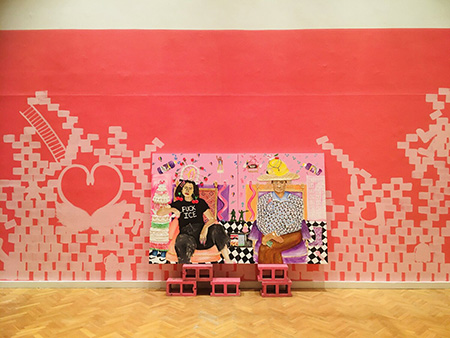

Yvette Mayorga’s installation, “F* is for ICE 1975-2018 (After Portrait of Innocent X, c. 1650, Diego Velázquez)” dominates a wall of the gallery by virtue of its hot pink palette. Thick, frosting-like paint application and bold, graphic imagery are more than capable of luring a viewer from across the room. I watched a couple in their 60s posed gleefully for a smartphone photo in front of Mayorga’s portraits, one of which features a figure wearing a bold, “FUCK ICE” tshirt. Mayorga’s work is Instagram-ready, and its combination of sweetness, joy, pride and fury is so on-point that we are compelled to join right in, and then post it for the world to see.

By contract, immediately adjacent to this audacious installation is one of the subtlest works in the exhibition. Maryam Taghavi’s “Reconstitution” can’t truly be experienced from anywhere but up close. What at first appears to be vinyl words on the wall, is not that at all. Only when one steps close is it apparent that the words are actually cut through the drywall, and beyond the wall is a mirror that reflects our own curious, gawking eyes back at us through the letters of the Preamble to the Constitution — written in Farsi. In Taghavi’s piece, the Constitution is simultaneously present and absent, reinforcing the notion that the rights it outlines are not a guarantee for all.

One of the few pieces in “In Flux” that does not depend upon an installation is Ji Yang’s “How to Cook Pigeon.” The work is a trifold brochure with step-by-step instructions for hunting, gutting and preparing Chicago’s pigeons in order to consume the FDA’s recommended 2,000 calories per person per day. The artist’s instructions (finding a garbage bag to fashion into a pigeon-capturing device, locating a bathroom with hot running water for cleaning the bird, where to get free salt and pepper to season the meat, digging a hole for a “stove” of sorts) are written in a deadpan, no-nonsense tone. The tone sets a fantastically ironic contrast to the absurdity the work addresses. Not only does Yang’s brochure (bright red, and designed like a take-out menu) allude to Chicago’s issues with food deserts in its various neighborhoods with at-risk populations, but it’s also a razor-sharp critique of the prejudices Americans have towards Asian culture. In a time when the Republican party is politically exploiting racial stereotypes more than its has in decades, misrepresenting the diets of Chinese people in the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, Yang’s work is a masterful, sarcastic slap back.

Moises Salazar’s earnest “In Flux” scatters a series of figurative sculptures throughout one of the exhibition’s galleries. In “El Aguante,” “No me dejes,” “Vamos estar bien” and “Cuerpas desechables,” child-sized bodies lie on the floor and under silver emergency blankets, or are huddled together in the corners of the room. While the figures’ ceramic hands and feet are crafted with careful realism, the rest of their bodies are covered in layers of ruffled crepe paper to resemble colorful piñatas. There’s a simplicity to the gesture and directness in its reference, but a profound complexity in their concept. These sculptures are simultaneously delightful and tragic, evoking celebration and detention. They underscore the humanity and the anonymity of the children. Clad as they are like piñatas, there’s also a palpable sense of imminent danger, as if at any moment they could be battered where they lie.