“Man screams from the depths of his soul; the whole era becomes a single, piercing shriek. Art also screams, into the deep darkness, screams for help, screams for the spirit. This is Expressionism.”

— Hermann Bahr

Austrian art critic and playwright Hermann Bahr (1863-1934) was one of the first to write about the cultural movement he termed Expressionism. Bahr did so in the early decades of the twentieth century, during the rise of Fascism. Today, Los Angeles artist Randi Matushevitz deploys Expressionism to respond to parallel cultural developments: the pervasive sexism, blatant racism, violent homophobia and rampant white supremacism of our current era.

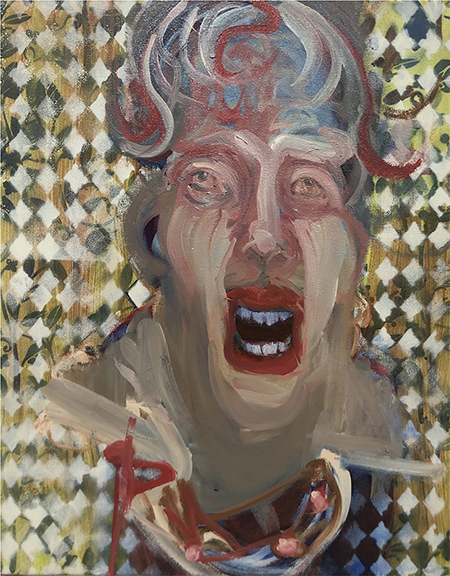

The early Expressionists introduced exaggerated and distorted forms; intense, non-local color; and adamant, frequently harsh brushwork in order to convey their emotional response to the horrors of their time. Matushevitz reinterprets these expressive devices to create dynamic figurative compositions and resonant symbols floating in dark, churning worlds.

Because early Expressionists like Ernest Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff rejected academic standards of idealized anatomy and illusionistic space, the Nazis labeled them "degenerate." They destroyed hundreds of Expressionist artworks. They tortured and imprisoned several of the artists. A century later, although Matushevitz's paintings can be seen as offsprings of the European Expressionists, it's unlikely she will be labeled degenerate or thrown in jail because of her work. Instead, we recognize her as part of the honorable lineage that started with the Europeans, morphed into the work of Jackson Pollock and his Abstract Expressionist entourage, then climaxed in the late twentieth century with Jean Michel Basquiat.

German Expressionist Max Beckmann wrote, "Art is creative for the sake of realization, not for amusement: for transfiguration, not for the sake of play. It is the quest of our self that drives us along the eternal and never-ending journey we must all make." Matushevitz's oeuvre gives voice to that same journey, as it embodies and reveals the human condition: our quest for connection and the pain we all suffer as part of this earthly existence.

She conveys that embodiment through fierce ghostly figures that scowl and howl and dream, their faces declaring the intensity of their experience in sardonic contortions. Black lines snake around a cheek. A white ear is transformed into a pointed horn. Heavy black feet are anchored by uneasy red contours. A dense leaden sky looms heavy over a fractured landscape. Circular discs of color and texture shower down onto denuded fields. A tiny human sinks into a well, recalling some of the miniature figures anguishing in the torments of Hieronymous Bosch's Hell.

In her current work Matushevitz expands her painting practice to include video, animating these haunted faces so that they silently speak or scream or moan. Howling in anxious frustration, mouths open to reveal discouncertingly "real" teeth. The rubbery facial distortions, the uneasy contrast between painted and actual features, and the agonizing silence of their attempts at communication make these new animated portraits even more disturbing than the artist's earlier ones. It's as if Francis Bacon's most disconcerting figures have come to life in a new century. Are they modern-day Cassandras? Victims of the pandemic? Perhaps they are casualties of the current political turmoil. Or do they suffer from the extremes of climate change?

Matushevitz addresses the troubling destruction of our natural environment, depicting a realm more akin to a zombie apocalypse than our flesh and blood domain. The only lights are uneasy windows of Day-Glo chartreuse, the only brilliance a sickly fluorescent orange. The artist's dystopian perspective is assertively ugly and impressively powerful. She performs artistic alchemy, allowing her intensely rendered marks to fuse with darkness and light in order to express the very nature of existence. Under all the expressive — even assaultive — distortions, there remains enduring hope: hope that we will survive, hope that we will continue to seek connectivity, and hope that creativity is the best path to do so. Within all the intense expression, Matushevitz reveals the beauty of the human condition.