There are two questions I like to ask myself before giving an exhibition the thumbs up or thumbs down. One, does the art push boundaries, in terms of mediums and messages, in ways that challenge my brain? Two, does the artist summon ideas and evoke interpretations that reflect our fraught times, even if the commentary is more subtle than overt? Neither question is exclusionary. I’m a receptive viewer of art, no matter how unorthodox its presentation or sociopolitical its posture. If an artist injects even a trace of humor I tend to like the work even more.

Which is why I am so drawn to the work of Denver artist Shawn Huckins, who satirically captures our social media-crazed society while asking critical questions about the withering-away of rules of discourse and communicative mores. His paintings mash up classical portraiture with text messages, tweets, hashtags, slang and the like, the language superimposed on the portraits in large, blocky white letters. One of his best-known series, from 2013, is “The American Revolution Revolution.” Consisting of more than two dozen acrylics on canvas, they demonstrate Huckins’ modus operandi of meticulously re-creating neoclassical American paintings — think John Singleton Copley, Rembrandt Peale and Gilbert Stuart — all by hand. Even the superimposed lettering is hand-painted in white, after areas are masked off. Ultimately, the texts and tweets, which are culled by Huckins from strangers’ online conversations and posts, have the effect of photobombing the otherwise staid portraiture or pastoral tableaux. The messages are sometimes silly, sometimes full of double meanings, but often rife with misspellings, abbreviations and the kind of profanities currently permeating our language. They upstage the underlying, more genteel scenes, obscuring key elements to make a point about the contrast between past and present.

One of my favorites from the series is the reimagining of Copley’s 1770 portrait of “Lemuel Cox.” Huckins’ take: “Lemuel Cox: What the Fuck,” a 30-by-28-inch acrylic with “WHADDA FACKK” emblazoned across the subject’s face. A more recent painting, “Boy in a Red Waistcoat: Descending Blah Blah Blah,” is based on a Paul Cézanne work and is “defaced” by the word “blah” repeating itself as it topples to the bottom of the canvas. Why these particular mash-ups? In Huckins’ view, they are subversive juxtapositions, pitting our collective memory of civility, thoughtful discourse, and formality in previous centuries against the ungrammatical holy mess (pardon my English teacher bias coming through) dominating 21st-century digital communication, revolutionary as our digital times may be.

Another notable series of mash-ups includes “The American ___tier,” where the paintings idyllically depict the 19th-century American frontier in landscapes and portraits but share the canvas with the blaring crudeness of block messages such as “I MEAN LIK, I RLY CANT EVEN” and “BO$$.” Viewers are free to insert another f-word in the intentional blank space in the series’ title. A later series called “The Erasures” replaces the block lettering with hand-painted gray and white checkerboards, white scribbles, white X’s, and other pixel-like representations of computer-generated erasures. In “Nothing Rhymes With Orange” the checkerboard creeps all the way up to the nose of a portrait of George Washington copied from the White House’s art collection, more than halfway erasing it. In an artist’s statement, Huckins sums up his intentions with the phrase “the fragility of legacy.” In addition to the frequent theme of the devolution of language, it’s also evident that he’s concerned about climate change and the political upheaval wrought by the 2016 election. Those themes and more make “the fragility of legacy” an especially pertinent phrase, worthy of using in certain conversations.

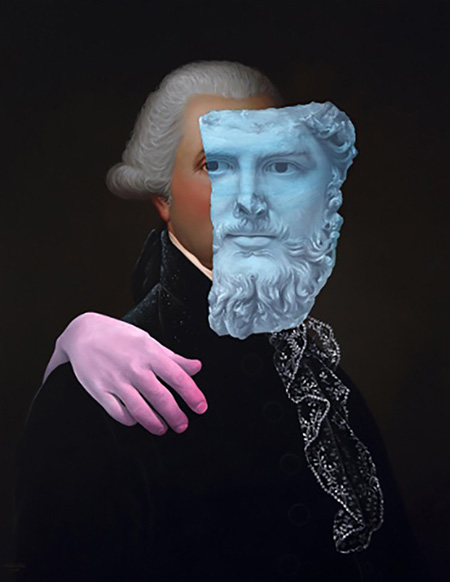

“Fool’s Errand.” Huckins’ newest series, goes on view at K Contemporary in Denver this month under pandemic-era rules of timed entry that play right into the artist’s hands. Huckins continues his caustic tone by letting the re-created classical portraiture give way to depictions of shards from classical Roman sculpture. Primed, you can feel the collapse of a society and its fall from grace in these images. Ghostly, disembodied hands placed on the subjects suggest sinister manipulations, symbolizing the corrosion of the country’s venerated past. In “(Samuel Verplanck)” the original by Copley is reimagined with a pink mask that appropriates the eyes of a Roman statue and with a floating white hand that grasps the man’s shoulder. The message is that chaos and dysfunction, far from arriving unexpectedly were always just biding their time.

So if Huckins’ work engages through humor, that’s only the first moments. It sticks with us because it speaks to our time, warning of disintegration and decay, if not obliteration. The genteel times epitomized by formal poses, powdered wigs and tricornered hats — idealized though they may be — don’t stand a chance against rough-and-tumble babel and rants, cannot compete against an unfortunate culture of blurting out inanities and un-truths. Like Huckins, I worry that the false gratification of digital-speak jeopardizes those all-American virtues of accuracy, balance, clarity and judiciousness. Luckily, his paintings also provide us with balm for our country’s crisis-filled existence. They intermingle jest with seriousness, brashness with topicality. What satisfaction to recall them whenever events out of Washington tempt me to roll my eyes, turn off the news, and say, “WHADDA FACKK.”